Battle of Gettysburg Buff

A website for Civil War

buffs interested in the

Battle of Gettysburg

More Odds and Ends

I hope you will find the topics and information on this page interesting and informative:

The Pipe Creek CircularThe Pipe Creek Circular, which was an order written by General George Meade late on the night of June 30, is usually given little thought by anyone studying the battle unless they read where it was used to criticize General Meade as being an indecisive and/or timid commanding general. That is truly a shame, for this order exemplifies, at least in my opinion, the brilliance of such a detailed and flexible plan that fully complied with his orders from Washington D.C. to locate and engage the enemy but while still covering both that city and Baltimore as well.

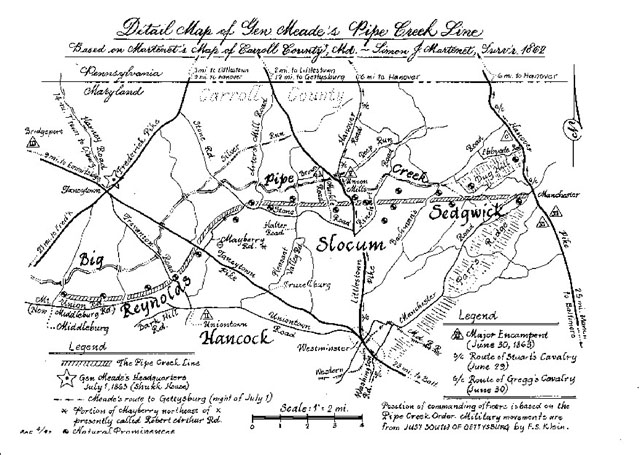

The Pipe Creek Circular, which thoroughly elaborated how, if the order needed to be carried out, all of the individual Union Corps would fall back to a roughly 20-mile long defensive position on the rolling hills along Big Pipe Creek from Middleburg, Maryland to Manchester, Maryland (see the map below):

(Map courtesy of Ronald A. Church)The topography of this area also allowed the Union Army the option of switching to offensive operations, provided for good communications and a road network along the rear of the line and, in addition, to the main supply base only 8 miles away at Westminster, Maryland.

There is still some dispute as to whether or not all of the Union Corps commanders and General John Buford received the order that was actually sent out on July 1 but was later rescinded when General John Reynolds decided to stay and fight it out. It is important to remember that those who did receive the Pipe Creek Circular (like Generals Henry Slocum and Dan Sickles, for example) no doubt had it in mind when determining when and how they responded to the urgent pleas for support from General Howard and his XI Corps on the left wing that was already engaged in action.

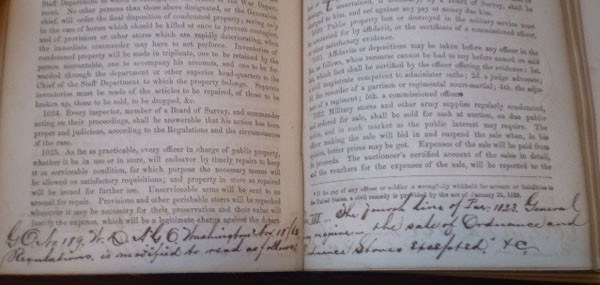

Here is the text of the Pipe Creek Circular:CIRCULAR

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF THE POTOMAC

Taneytown, July 1, 1863From information received, the commanding general is satisfied that the object of the movement of the army in this direction has been accomplished, viz, the relief of Harrisburg, and the prevention of the enemy's intended invasion of Philadelphia, &c., beyond the Susquehanna. It is no longer his intention to assume the offensive until the enemy's movements or position should render such an operation certain of success.

If the enemy assume the offensive, and attack, it is his intention, after holding them in check sufficiently long, to withdraw the trains and other impedimenta; to Withdraw the army from its present position, and form line of battle with the left resting in the neighborhood of Middleburg, and the right at Manchester, the general direction being that of Pipe Creek. For this purpose, General Reynolds, in command of the left, will withdraw the force at present at Gettysburg, two corps by the road to Taneytown and Westminster, and, after crossing Pipe Creek, deploy toward Middleburg. The corps at Emmitsburg will be withdrawn, via Mechanicsville, to Middleburg, or, if a more direct route can be found leaving Taneytown to their left, to withdraw direct to Middleburg.

General Slocum will assume command of the two corps at Hanover and Two Taverns, and withdraw them, via Union Mills, deploying one to the right and one to the left, after crossing Pipe Creek, connecting on the left with General Reynolds, and communicating his right to General Sedgwick at Manchester, who will connect with him and form the right.

The time for falling back can only be developed by circumstances. Whenever such circumstances arise as would seem to indicate the necessity for falling back and assuming this general line indicated, notice of such movement will be at once communicated to these headquarters and to all adjoining corps commanders.

The Second Corps now at Taneytown will be held in reserve in the vicinity of Uniontown and Frizellburg, to be thrown to the point of strongest attack, should the enemy make it. In the event of these movements being necessary, the trains and impedimenta will all be sent to the rear of Westminster.

Corps commanders, with their officers commanding artillery and the divisions, should make themselves thoroughly familiar with the country indicated, all the roads and positions, so that no possible confusion can ensue, and that the movement, if made, be done with good order, precision, and care, without loss or any detriment to the morale of the troops.

The commanders of corps are requested to communicate at once the nature of their present positions, and their ability to hold them in case of any sudden attack at any point by the enemy.

This order is communicated, that a general plan, perfectly understood by all, may be had for receiving attack, if made in strong force, upon any portion of our present position.

Developments may cause the commanding general to assume the offensive from his present positions.

The Artillery Reserve will, in the event of the general movement indicated, move to the rear of Frizellburg, and be placed in position, or sent to corps, as circumstances may require, under the general supervision of the chief of artillery.

The chief quartermaster will, in case of the general movement indicated, give directions for the orderly and proper position of the trains in rear of Westminster.

All the trains will keep well to the right of the road in moving, and, in case of any accident requiring a halt, the team must be hauled out of the line, and not delay the movements.

The trains ordered to Union Bridge in these events will be sent to Westminster.

General headquarters will be, in case of this movement, at Frizellburg; General Slocum as near Union Mills as the line will render best for him; General Reynolds at or near the road from Taneytown to l.

The chief of artillery will examine the line, and select positions for artillery.

The cavalry will be held on the right and left flanks after the movement is completed. Previous to its completion, it will, as now directed, cover the front and exterior lines, well out.

The commands must be prepared for a movement, and, in the event of the enemy attacking us on the ground indicated herein, to follow up any repulse.

The chief signal officer will examine the line thoroughly, and at once, upon the commencement of this movement, extend telegraphic communication from each of the following points to general headquarters near Frizellburg, viz, Manchester, Union Mills, Middleburg, and the Taneytown road.

All true Union people should be advised to harass and annoy the enemy in every way, to send in information, and taught how to do it; giving regiments by number of colors, number of guns, generals' names, &c. All their supplies brought to us will be paid for, and not fall into the enemy's hands.

Roads and ways to move to the right or left of the general line should be studied and thoroughly understood. All movements of troops should be concealed, and our dispositions kept from the enemy. Their knowledge of these dispositions would be fatal to our success, and the greatest care must be taken to prevent such an occurrence.By command of Major-General Meade:

S. WILLIAMS,

Assistant Adjutant-GeneralMEMORANDA

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF THE POTOMAC

July 1, 1863So much of the instructions contained in the circular of this date, just sent to you, as relates to the withdrawal of the corps at Emmitsburg should read as follows:

The corps at Emmitsburg should be withdrawn, via Mechanics-town, to Middleburg, or, if a more direct route can be found leaving Taneytown to the left, to withdraw direct to Middleburg.

Please correct the circular accordingly.

By command of Major-General Meade:

S. WILLIAMS,

Assistant Adjutant-General

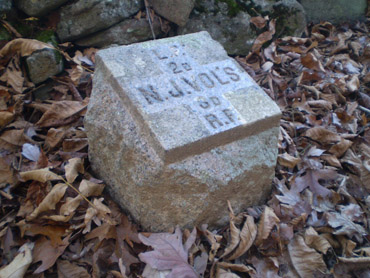

The monument and marker to the 26th Pennsylvania Emergency RegimentWhile most battlefield visitors have more than likely seen the monument and two ground-level markers to the 26th Pennsylvania Emergency Regiment which are located 3 blocks west of the square at the “Y” intersection of Chambersburg Street (Route 30 West) and Springs Avenue, there is another smaller marker about 3 miles further west of town roughly 100 yards east of Marsh Creek on the north side of the road. This marker indicates the general area where this newly formed regiment (it was only mustered in on June 22 with about 750 men and included about 21 students of Pennsylvania College in Company A) had set up camp and briefly encountered General John B. Gordon’s Brigade on June 26. After their pickets fired a few rounds at the oncoming Confederate troops, the 26th Pennsylvania Emergency Regiment, commanded by Colonel William W. Jennings, wisely retreated to the northwest, ultimately reaching Harrisburg on June 28:

(Photo courtesy of Mike Waricher and the GNMP)It is also important to note that at least some students of Pennsylvania College “volunteered” in other capacities during the battle. Two of those students were Michael Colver (a senior from Olivet, Pennsylvania) and Horatio J. Watkins (a junior from Hagerstown, Maryland), who would often assist in providing medical treatment to both wounded Union and Confederate soldiers at several locations in and around town during and after the battle. In the 1902 edition of the Spectrum, the yearbook of Pennsylvania College (which became Gettysburg College in 1921), both Colver and Watkins recounted their amazing stories a full thirty-nine years after the battle. For more information on the amazing accounts of those students, read the article “Students of Battle: Michael Colver, Horatio Watkins, and Pennsylvania College in the Crosshairs of Battle”at https://gettysburgcompiler.org/tag/alexander-dau.

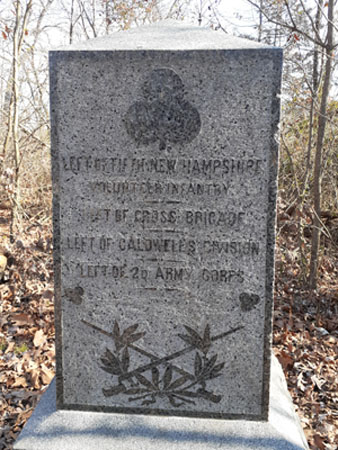

The U.S. RegularsWhile they may not have played a large role in one of the more well-known phases of the battle, the bravery and sacrifices of the two infantry brigades of U.S. Regulars in General Romeyn B. Ayres’ Second Division of General George Sykes’ Union V Corps on July 2 should not be overlooked or forgotten. The First Brigade, commanded by Colonel Hannibal Day, consisted of the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment, 4th U.S. Infantry Regiment, 6th U.S. Infantry Regiment, 12th U.S. Infantry Regiment, and 14th U.S. Infantry Regiment. The Second Brigade, commanded by Colonel Sidney Burbank, consisted of the 2nd U.S. Infantry Regiment, 7th U.S. Infantry Regiment, 10th U.S. Infantry Regiment, 11th U.S. Infantry Regiment, and 17th U.S. Infantry Regiment. Comprised of relatively small regiments (the 10th U.S. Infantry Regiment only had 3 Companies, and two other regiments only had 4 Companies), the two brigades moved from their initial position on the northern slope of Little Round Top to Houck’s Ridge on the eastern edge of and then into the Wheatfield to support General John C. Caldwell’s Division of the Union II Corps. Encountering four brigades of Confederate infantry on their front and both flanks, the two brigades of U.S. Regulars eventually began to fall back as if on drill, stopping at intervals to turn around and return fire as they slowly and methodically retreated to their initial position on the northern slope of Little Round Top. When it was all said and done, these two brigades of U.S. Regulars totaling approximately 2,600 soldiers suffered roughly 800 casualties in about an hour. One Union soldier in a nearby state volunteer regiment is reported to have once said something like “For two years, the Regulars taught us how to act like soldiers. At Gettysburg, they showed us how to die like soldiers."

Most of the individual monuments to these regiments are easily visible along Ayres Avenue on the crest of Houck’s Ridge):

However, the monument to the 17th U.S. Infantry Regiment is located in a small ravine below a stone wall and roughly 40 yards south of the monument to the 11th U.S. Infantry Regiment:

In addition, the monument to the 14th U.S. Infantry Regiment is located roughly 55 yards southeast of the crest of Houck’s Ridge and about 55 yards west of Crawford Avenue:

It should also be noted that there was one more regiment of U.S. Regulars at Gettysburg, the 8th U.S. Infantry Regiment, which served as part of the Headquarters Provost Guard for General George Meade at the Lydia Leister house on the west side of the Taneytown Road behind Cemetery Ridge:

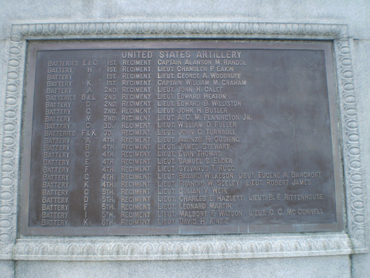

It is fitting, though, that one of the most prominent monuments on Cemetery Ridge is the tall obelisk monument honoring all of the U.S. Regular Army infantry, artillery, cavalry and engineer units that served in the Gettysburg Campaign:

They also servedThere are at least two small markers on the battlefield to honor Union troops that did not take part in any real fighting but served necessary roles nonetheless. Located along the east side of the Baltimore Pike roughly 70 yards south of the entrance to the new Visitor Center is the small marker for the 10th Maine Infantry Battalion, commanded by Captain John D. Beardsley, which served as the Provost Guard for General Henry W. Slocum’s XII Corps headquarters:

Another small marker, located just a short distance west of the Baltimore Pike at the intersection of Granite School House Lane and Blacksmith Shop Road, is for the 4th New Jersey Infantry Regiment, commanded by Major Charles Ewing and was part of the First New Jersey Brigade (see the “Faces of the battle” section on my “Something Different” page). Companies A, C, and H served as the brigade’s Provost Guard while the rest of the regiment guarded the Union Artillery Reserve train:

And two women too...One of the most noticeable and unusual monuments on the battlefield is the “castle” monument to the 12th New York and 44th New York Infantry Regiments on Little Round Top:

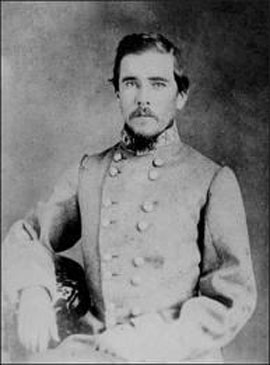

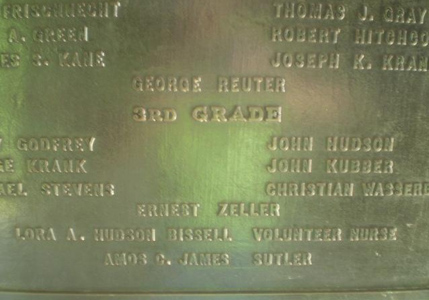

In addition to the unique exterior design, an unusual aspect of the monument is in the interior on the bronze tablets listing not only individual officers and lower ranking soldiers but also commissary sergeants, hospital stewards, band members, and sutlers. But what is truly unusual is that these plaques also include the names of two women: Lora A. Hudson Bissell and Harriet Weld Corning.

Lora A. Hudson Bissell, the daughter of a Baptist clergyman, was born near Albany, New York in 1839. She became a schoolteacher and wrote the words to the poem “Ellsworth Avengers” to honor Colonel Elmer Ellsworth of the 11th New York Infantry Regiment, the first Union officer killed in the Civil War in May of 1861. Members of the 44th New York Infantry Regiment learned of the song, called upon Miss Hudson and asked permission to adopt the words as its regimental song. Learning of her desire to serve her country, they invited her to accompany them as the "Daughter of the Regiment." Miss Hudson did so, and joined the regiment as a volunteer nurse, later marrying Dr. Elias Bissell, Assistant Surgeon of the 44th New York Infantry Regiment, in 1864.

(Image courtesy of Forest Lawn

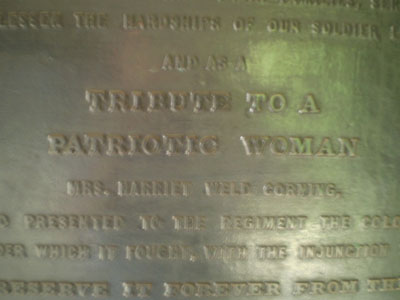

Cemetery in Buffalo, New York)Harriet Weld Corning was a member of the wealthy and eminent Weld family of Roxbury, Massachusetts. Born in 1793, she later married Erastus Corning, an enterprising businessman from Norwich, Connecticut who made his mark in hardware, nail and iron works, and other business ventures in and near Albany, New York. He also became involved in politics on the state level as well as serving as a U.S. Congressman in the late 1850’s and early 1860’s. As one of the plaques inside the monument states:

“And as a

Tribute to a

Patriotic Woman

Mrs. Harriet Weld Corning,

who presented the 44th regiment the colors

under which it fought, with the injunction to

"preserve it forever from the traitor's

touch and let no coward's hand trail it in the dust."

(Image courtesy of the Albany

Institute of History & Art)And now you know about the only regimental monument on the Gettysburg battlefield which honors two women.

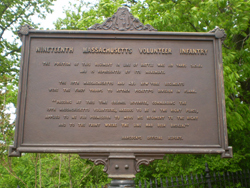

Original Massachusetts infantry regiment markers

The metal markers for the Massachusetts infantry regiments which can be found on the south side of the “copse of trees” on Cemetery Ridge (the 15th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, the 19th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, and the 20th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment) are not original. To make a long story short, the stone monuments to these three regiments marking where they helped to repulse “Pickett’s Charge” were later moved to their original “line of battle” positions. Afterward, veterans of those units in the early 1900’s asked for and were given permission to have iron posts installed with signs denoting their “advanced positions”, but the signposts were later removed by the National Park Service in the 1950’s as being superfluous (The Civil War Round Table of Eastern Pennsylvania funded the replacement of these three signposts in 1993, and are the ones we see today --- for more information, read “Isn’t This Glorious!”: The 15th, 19th, and 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiments at Gettysburg’s Copse of Trees” by Edwin R. Root and Jeffrey D. Stocker). Although all of these original regimental signposts have long disappeared, some of the uniquely shaped bases can still be found elsewhere on the battlefield. One of these (most likely to the 33rd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment) is located on the east side of East Cemetery Hill along the north side of the second stone wall (out of the five parallel stone walls, and counting them from south to north) about halfway down to Wainwright Avenue:

(Photo courtesy of the GNMP and Mike Waricher)

Other bases can be found on Little Round Top, Munshower’s Knoll (the location of the equestrian monument to Union VI Corps commander General John Sedgwick) just north of Little Round Top, and the Wheatfield. So, if you are in the vicinity of a monument to a Massachusetts infantry regiment, take a look around and see if you can find one of those old bases:

18th Massachusetts (Little Round Top) --- at stone wall 25 yards northwest of the 83rd Pennsylvania

22 Massachusetts (Little Round Top) --- at stone wall 55 yards northwest of the 83rd Pennsylvania

32nd Massachusetts (Wheatfield) --- at stone wall 85 yards east of the 17th Maine

33rd Massachusetts (Cemetery Hill) --- at stone wall 80 yards west of 14th Indiana right flank marker

37th Massachusetts (Munshower’s Knoll) --- north of Battery C, 1st New York Artillery

Other monuments that have been movedIn addition to the well-known statue located along the east side of Stone Avenue on McPherson's Ridge of “citizen soldier” John Burns (see the “Speaking of John Burns” section on my “Odds and Ends” page), there are two other original bases of monuments that were moved which are also fairly easy to find.

One of them is the original base for the monument to the 5th New York Cavalry Regiment, commanded by Major John Hammond and one of the regiments that participated in the ill-fated cavalry charge by Union General Elon Farnsworth’s Brigade (see the “The South Cavalry Battlefield --- the other cavalry action on July 3” section on my “Off the Usual Path” page). The original base is roughly 4 feet by 8 feet and located about 20 yards off of the west side of South Confederate Avenue about halfway up the hill as you climb northward along the western base of Big Round Top and the large parking area on the left. Look for the twin trees on your left and only a few feet off the road (see the left photo below):

The other one is the original base for the monument to the 16th Vermont Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Wheelock G. Veazey. The monument was originally located approximately 1,000 yards west of its current position (as the bronze plaque that was attached to the new base after the monument was moved now indicates), which is on the east side of Hancock Avenue along Cemetery Ridge just north of Pleasonton Avenue. What is really interesting to me is that apparently the original base was not left where it was (as was in the case of the other bases mentioned above), but was moved approximately 1,120 yards (i.e., about 120 yards further east of the monument’s new location) directly to the east and then discarded along a small stone wall running parallel to Pleasonton Avenue. The monument may have been moved when Camp Colt was built in that area (see the “Camp Colt” section on my “Odds and Ends” page), and a larger base was necessary to accommodate the bronze plaque, but if the base shown in the bottom right photo is indeed the original base, then why was it discarded there ???

The monument to the 2nd Delaware Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel William P. Baily was another monument that had been moved and the remnants its original base can still be found if you look carefully. The monument was initially placed roughly in the middle of the famous Wheatfield about 450 yards northeast of its current location on the east side of Brooke Avenue where it was later moved to its “line of battle” with the other monuments to the regiments of Colonel John R. Brooke’s Brigade approximately 250 yards southeast of the George Rose farm. The remnants of the original base are located in a tiny clump of brush roughly halfway between the monument to the 61st New York Infantry Regiment and the monument to Battery D of the 1st New York Light Artillery:

Here is a photo showing the original position of the monument to the 2nd Delaware Infantry Regiment (the monument to General Samuel Zook along the south side of the Wheatfield Road is visible in the background):

(Photo courtesy of the GNMP and Mike Waricher)Here is a current photo taken in the approximate area as the photo above as well as photo of the monument on Brooke Avenue:

Yet another monument which was moved is the monument to the 5th Maine Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel Clark S. Edwards. The monument, located roughly 50 yards north of the Wheatfield Road approximately 65 yards west of its intersection with Sedgwick Avenue north of Little Round Top, was originally located atop a rock on the northern slope of Little Round Top and roughly 200 yards south of its current position. The rock (with chisel marks still visible) can still be found roughly 75 yards west of the monument to the 121st New York Infantry Regiment (see the “Faces of the battle” section on my “Something Different” page) and 30 yards north of the monument to Battery L of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery commanded by Captain Frank C. Gibbs:

Another interesting monument which was also moved is the monument to the 16th Michigan Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel Norval E. Welch. The monument, located on the lower “ledge” of the west side of Little Round Top, was originally placed at ground level but later moved atop a nearby boulder; the original base measuring approximately 44 inches by 88 inches can still be found roughly 15 yards southeast of the monument and on the east side of the rock wall:

For more information and photographs of the original locations of the monuments to the 2nd Delaware Infantry Regiment, the 5th Maine Infantry Regiment, and the 16th Michigan Infantry Regiment, I recommend the book “Gettysburg’s Battlefield Photographer – William H. Tipton” by Licensed Battlefield Guide Tim Smith (see my “Books Worth Reading” page”), who was extremely helpful in my search for the original rock base of the monument to the 5th Maine Infantry Regiment --- thank you very much, Tim !!!

The regiment with five monuments/markersMany Union military units have more than one monument or marker on the battlefield (usually occurring as a result of newer and more elaborate monuments being constructed to replace an earlier one, with the original monument being moved to another location where that particular unit was also positioned during the battle). While the 95th New York Infantry Regiment (also known as the “Warren Rifles”) was not one of these units, it does have the distinction of having the most monuments/markers --- five !!!

Commanded by Colonel George H. Biddle (and then by Major Edward Pye after Biddle was wounded on July 1), the 95th New York Infantry Regiment (Second Brigade, First Division of the Union I Corps) has its monument on the east side of Reynolds Avenue monument along the south side of the famous “railroad cut”:

There are also four small stone markers on the battlefield that are often overlooked (three of them in the various areas of the fighting the regiment was involved in on July 1, and one on Culp’s Hill where it was positioned on July 2 and 3:

1. On the east side of Stone Avenue on McPherson’s Ridge roughly 50 yards north of the John Burns monument and about 10 yards off the road behind the wooden fence:

2. On the north side of Wadsworth Avenue at the 90-degree bend in the road about 200 yards east of the “T” intersection with Buford Avenue and Reynolds Avenue:

3. On Seminary Ridge at the southeast corner of the “T” intersection of the Chambersburg Pike (Route 30) and West Confederate Avenue:

4. On the east side of the summit of Culp’s Hill approximately 25 yards to the right of the monument to the 7th Indiana Infantry Regiment and about 5 yards off the road:

The “faugh a ballaugh” monumentIn addition to the famous “Irish Brigade” monument (which honors the 63rd New York Infantry Regiment, the 69th New York Infantry Regiment, and the 88th New York Infantry Regiment) with the depiction of an Irish wolfhound (see the “Regimental animal mascots and monuments” section on my “Something Different” page), there is one monument nearby that contains the phrase “faugh a ballaugh”, which is a Gaelic phrase meaning “clear the way”. That monument, located roughly 50 yards further west around the bend in the loop on Sickles Avenue, is to the 28th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, another regiment in that brigade:

Yet another regiment in the Irish Brigade, the 116th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment composed primarily of Irish immigrants from Philadelphia, has its monument just 20 yards away on the other side of the road and does not have that historic phrase. I wonder why only the monument to the 28th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment has that phrase “faugh a ballaugh” ???

The monument with two basesThere are several monuments to infantry regiments of General Frank Wheaton’s Third Brigade, Third Division, of General John Sedgwick’s Union VI Corps along the east side of the dirt lane to the John Weikert farm (REMEMBER --- THE RESIDENCE IS ON PRIVATE PROPERTY) located north of the "T" intersection of Wheatfield Road and Crawford Avenue. These are the monuments (in the order from south to north as you go up the lane) to the 139th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, the 93rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, the 62nd New York Infantry Regiment, the 102nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, and the 98th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment (located roughly 60 yards behind the house). These regiments were among the reinforcements sent in to the “Valley of Death” near Little Round Top on July 2.

If you look closely at the monument to the 93rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment commanded by Major John I. Nevin, you will see remnants of the original base that were removed when the original monument was replaced by a newer monument that was placed on top of the lower section of the original base:

The original monument is roughly 400 yards to the east and only 20 yards off to the west side of Sedgwick Avenue almost directly across from the equestrian monument to General John Sedgwick about 150 yards north of the intersection of Sedgwick Avenue and Sykes Avenue:

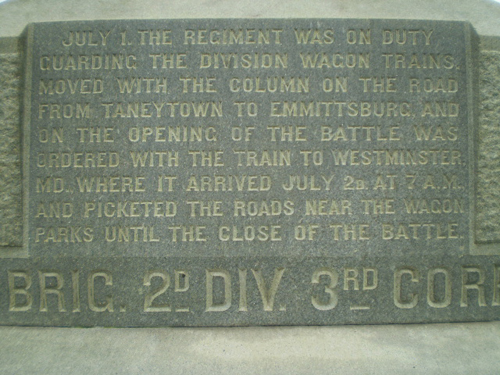

The monument (and flank markers) to the regiment that wasn’t thereWhile there are several markers and tablets on the battlefield to military units that were involved in the Gettysburg Campaign but not actually at the battle, there is one monument located just north of the Pennsylvania Monument on the south side of Pleasonton Avenue to the 84th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment. Commanded by Colonel Milton Opp, the regiment was guarding their division’s supply trains in Westminster, Maryland. Although that information is stated on the monument, if you look nearby, you will see something even more interesting --- flank markers for the regiment !!!

It is my understanding that the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association, which was formed on April 30, 1864, had specific rules it adopted in 1887 for the placement of monuments, including:

VI. The monument must be on the line of battle held by the brigade unless the regiment was detached, and if possible the right and left flanks of the regiment or battery must be marked with stones not less than two feet in height.

So, why were flank markers either required or approved even though the regiment was indeed on detached duty during the battle ???

Union regiments and batteries which do not have monumentsThere were several Union Army units, all part of the VI Corps, which were indeed present at the Battle of Gettysburg but do not have any monument or marker:

33rd New York Infantry Regiment

1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, Battery C

1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, Battery GIn the case of the 33rd New York Infantry Regiment, only a small detachment was present and was unofficially attached to the 49th New York Infantry Regiment. Why the Rhode Island legislation of 1885 providing for monuments at Gettysburg did not include these two artillery batteries is unknown.

The other flagpoleIn addition to the flagpole on the East Cavalry Battlefield honoring Union Lieutenant William Brooke-Rawle (see the “Lesser known and visited monuments and small markers” section on my “Off the Usual Path” page), there is a flagpole on Barlow’s Knoll that marks the spot where Colonel Douglas Fowler, while commanding the 17th Connecticut Infantry Regiment on July 1, was struck and killed by an artillery shell. Located only 20 yards north of the regiment’s monument (which, by the way, has “Douglass Fowler” on it), the plaque on this flagpole, however, simply reads “ERECTED BY THE 17TH CONN. VOLS. ASS’N.” and does not mention Colonel Fowler at all:

Battle damaged structuresI would venture a guess that perhaps the most well known structure in Gettysburg that still shows battle damage is the Farnsworth House Inn located at 401 Baltimore Street (during the battle, it was the home of the Harvey Sweney family):

You can see many other structures with similar damage, such as the Jacob Stock house at 407 South Washington Street:

What is really interesting is that there are nine structures with artillery shells embedded in their walls (written accounts for some of the structures state that the shell is an unexploded one that was never removed, while accounts for others say the shell entered the structure but did not explode and then was later placed in the wall to commemorate the fact that the structure sustained battle damage):

George Crass-Henry Barbehenn house 218 N. Stratton St. 3-inch Reed shell

Gettysburg Female Institute 66-68 W. High St. 3-inch Reed shell

Gettysburg Methodist Parsonage 304 Baltimore St. 12-pounder cannon ball

John Kuhn house 221 N. Stratton St. 3-inch Hotchkiss shell

Moses McClean house 11 Baltimore St. 20-pounder Parrott shell

Caroline (Carrie) Sheads house 331 Buford Ave. 10-pounder Parrott shell

Samuel Schmucker house Seminary Ridge Ave. 10-pounder Parrott shell

David Troxell house 221 Chambersburg St. 3-inch Schenkl shell

Tyson Brothers photography studio 9 York St. 3-inch Hotchkiss shell

To read more about these structures, their occupants, and the artillery shells, I highly recommend the section “A Tour of Gettysburg’s Visual Battle Damage” by Licensed Battlefield Guide Tim Smith in the 1996 Volume 2 booklet entitled “Adams County History” published by the Adams County Historical Society and the Summer 2007 Edition (Volume 24, Issue 2) of the Blue & Gray Magazine (go to http://bluegraymagazine.com/store/index.html).

What's in a nameI would think that almost every Battle of Gettysburg buff knows a few of the other names that Little Round Top went by before the battle, such as "Sugar Loaf Hill” or just “Sugarloaf" or the "granite spur of Round Top", but there are many areas and geographic features that goes by more than one name. For example, Big Round Top was once referred to as Adam Lynn’s Hill (Adam Lynn was one of the earliest settlers of the area).

Other examples include those that were given a new name as a result of a specific military officer associated with the fighting there, such as Blocher’s Knoll being referred to as Barlow’s Knoll (after General Francis C. Barlow, and McKnight’s Hill being referred to as Stevens’ Knoll (after Captain Greenleaf T. Stevens). In addition, Raffensberger’s Hill became known as East Cemetery Hill, and McPherson’s Woods is used interchangeably with Herbst’s Woods (although McPherson’s Woods is actually a little farther east).

Local features which already had more than one name include Brickyard Lane, which was also known as Winebrenner’s Lane (located east of Cemetery Hill near present-day Wainwright Avenue); another example is Stevens’ Run, also known as “the Tiber”, and runs roughly north to south and is located roughly 250 yards east of Seminary Ridge:

It is also important to realize that the Farnsworth House Inn was actually the Harvey Sweney house (see the “Battle damaged structures” section on this page) during the time of the battle, and that General Elon Farnsworth never stayed or lived there.

Town names, as is often the case, have also changed. The present-day village of Barlow (renamed for General Francis C. Barlow), located about 5 miles south of Gettysburg on the Taneytown Road, was called Horner’s Mills at the time of the battle, and the present-day village of Flora Dale, located about 9 miles north of Gettysburg just above Biglerville, was called Wrightsville and should not be confused when reading about the town of Wrightsville in nearby York County.

I wonder how many people, though, know that Culp’s Hill was at one time also called “Raspberry Hill” because of the many raspberry bushes that grew there in abundance. So the next time you are exploring Culp’s Hill, see if you can spot some of the raspberry bushes which can still be found there.

In February of 2010, I was contacted by a Civil War reenactor and semi-retired educator who emailed me the text of a July 6, 1863 New York Times article by famous Civil War newspaper correspondent Samuel Wilkeson (whose son, Lieutenant Bayard Wilkeson, was mortally wounded on July 1 on Barlow’s Knoll while commanding Battery G of the 4th U.S. Artillery). In the newspaper article, the general vicinity of the famous “copse of trees” on Cemetery Ridge is referred to as “Crow Hill” !!!

West Point graduates at the Battle of GettysburgOne often reads about Union generals who were West Point graduates that fought against fellow classmates in the Confederate Army, but I had never really thought much about it until I received an email asking me if I knew (or could find out) exactly how many West Point graduates fought at Gettysburg. I did not know the answer, and the question was an interesting one, so I emailed Gettysburg National Park Service Ranger/Historian John Heiser. John informed me that according to a data sheet in the GNMP library files, there were 115 Union officers and 42 Confederate officers at Gettysburg who were West Point graduates. John also mailed me a copy of that data sheet, which was the basis for the charts I compiled below:

Adams, Julius W. (Captain) Hall, Norman J. (Colonel) Patrick, Marsena R. (General) Ames, Adelbert (General) Hamilton, Frank B. (Lieutenant) Paul, Gabriel R. (General) Andrews, John N. (Captain) Hancock, David P. (Captain) Pennington, Alexander C. (Lieutenant) Ayres, Romeyn B. (General) Hancock, Winfield S. (General) Pettes, William H. (Colonel) Baker, Eugene M. (Captain) Hardin, Martin D. (Colonel) Platt, Edward R. (Colonel) Bankhead, Henry C. (Colonel) Haupt, Herman (General) Pleasonton, Alfred (General) Barlow, John W. (Lieutenant) Hays, Alexander (General) Poland, John S. (Colonel) Barnes, James (General) Hays, William (General) Randol, Alanson M. (Captain) Beaumont, Eugene B. (Captain) Hazlett, Charles E. (Lieutenant) Reese, Chauncey B. (Captain) Benham, Henry W. (General) Howard, Oliver O. (General ) Remington, Philip H. (Lieutenant) Best, Clermont L. (Colonel) Howe, Albion P. (General) Reynolds, John F. (General) Bryan, Timothy (Colonel) Humphreys, Andrew A. (General ) Ruger, Thomas H. (General) Buford, John (General) Hunt, Henry J. (General) Russell, David A. (General) Burbank, Sidney (Colonel) Ingalls, Rufus J. (General) Ryan, George (Captain) Bush, Edward G. (Captain) Kellogg, Josiah H. (Colonel) Sanderson, James A. (Lieutenant) Calef, John H. (Lieutenant) Kent, Jacob F. (Colonel) Sawtelle, Charles G. (Colonel) Carroll, Samuel S. (Colonel) Kilpatrick, Judson (General) Schaff, Morris ((Lieutenant) Carter, Eugene (Major) Lancaster, James M. (Lieutenant) Schriver, Edmund (General) Claflin, Ira W. (Captain) Lockwood, Henry H. (General) Sedgwick, John (General) Clarke, Henry F. (Colonel) Lord, Richard S. (Captain) Slocum, Henry W. (General) Cushing, Alonzo (Lieutenant) Lynn, Daniel D. (Lieutenant) Sykes, George (General) Custer, George A. (General) Mackenzie, Ranald S. (Lieutenant) Tidball, John C. (Captain) Davis, Benjamin F. (Colonel) Martin, Leonard (Lieutenant) Torbert, Alfred T. A. (General) Davis, Nelson H. (Major) Martin, James P. (Captain) Turnbull, Charles N. (Captain) Day, Hannibal (Colonel) McCleary, John (Captain) Tyler, Robert O. (General) Doubleday, Abner (General) McCrea, Tulley (Captain) Upham, John J. (Captain) Edie, John R. (Lieutenant) McIntire, Samuel B. (Lieutenant) Upton, Emory (Colonel) Egan, John (Lieutenant) McKee, Samuel A. (Captain) Warner, Charles N. (Lieutenant) Eustis, Henry L. (Colonel) McQuesten, James F. (Lieutenant) Warner, Edward R. (Colonel) Flagler, Daniel W. (Captain) Meade, George G. (General) Warren, Gouverneur K. (General) Floyd-Jones, Delaney (Major) Mendell, George H. (Captain) Watson, Malbone F. (Lieutenant) Freedley, Henry W. (Captain) Merritt, Wesley W. (General) Webb, Alexander S. (General) Fuller, William D. (Lieutenant) Morgan, Charles H. (Colonel) Weed, Stephen H. (General) Garrard, Kenner (Colonel) Neill, Thomas H. (General) Whiting, Charles J. (Major) Gibbon, John (General) Newton, John (General) Williams, Seth (General) Gillespie, George L. (Lieutenant) Nicodemus, W. J. L. (Captain) Woodruff, George A. (Lieutenant) Greene, George S. (General) Norris, Charles E. (Captain) Wright, Horatio G. (General) Gregg, Daniel M. (General) Noyes, Henry E. (Captain) Griffin, Charles (General) O’Rorke, Patrick H. (Colonel)

Alexander, E. Porter (Colonel) Henry, Mathias W. (Major) Magruder, William T. (Captain) Anderson, Richard H. (General) Heth, Henry (General) McCreery, Jr., William (Captain) Baker, Laurence S. (Colonel) Hill, Ambrose P. (General) Mercer, John T. (Colonel) Beckham, Robert F. (Major) Hood, John B. (General) Pender, William D. (General) Bryan, Goode (Colonel) Huger, Frank (Major) Pendleton, William N. (General) Chambliss, John R. (Colonel) Johnson, Edward (General) Pickett, George E. (General) Chilton, Robert H. (Colonel) Jones, John M. (General) Ramseur, Stephen D. (General) Cole, Robert G. (Colonel) Jones, William E. (General) Robertson, Beverly H. (General) Corley, James L. (Colonel) Lee, Fitzhugh (General) Smead, Abner (Colonel) Daniel, Junius (General) Lee, Robert E. (General) Smith, W. Proctor (Colonel) Davis, J. Lucius (Colonel) Lomax, Lunsford L. (Colonel) Steuart, George H. (General) Early, Jubal A. (General) Long, Armistead L. (Colonel) Stuart, James E. B. (General) Ewell, Richard S. (General) Longstreet, James P. (General) Trimble, Isaac R. (General) Garnett, Richard B. (General) McLaws, Lafayette (General) Wilcox, Cadmus M. (General)

Virginia Military Institute graduates at the Battle of GettysburgThe Virginia Military Institute, founded in Lexington, Virginia in 1839, is often referred to as the “West Point of the South”. Listed below is a list of VMI graduates who were at the Battle of Gettysburg:

Allen, Robert C. (Colonel) Hambrick, Joseph A. (Major) Patton, Waller T. (Colonel) Baldwin, Briscoe G. (Colonel) Hannah, George B. (Lieutenant) Phillips, James J. (Captain) Bell, Robert F. (Captain) Harrison, Walter H. (Major) Pitzer, Andrew L. (Lieutenant) Bentley, William W. (Captain) Heth, Stockton (Lieutenant) Powell, William L. (Captain) Berkeley, Edmund (Major) Hill, Francis T. (Captain) Pryor, William H. (Major) Berkeley, Norborne (Colonel) Hill, John W. (Lieutenant) Randolph, William L. (Lieutenant) Boyd, Waller M. (Captain) Hutter, James R. (Captain) Rodes, Robert E. (General) Bray, William H. (Captain) James, John T. (Lieutenant) Selden, Miles C. Jr. (Lieutenant) Brown, Benjamin Jr. (Captain) Jones, Charles H. (Lieutenant) Smith, Frederick W. (Lieutenant) Burgwyn, Henry Jr. (Colonel) Jones, John W. (Captain) Smith, George H. (Colonel) Cabell, Henry C. (Colonel) Kyle, George G. (Captain) Smith, Thomas H. (Lieutenant) Callcote, Alexander D. (Colonel) Lane, James H. (General) Stockton, John N. C. (Adjutant) Carter, Edward (Captain) Latimer, Joseph W. (Major) Stuart, William D. (Colonel) Carter, Thomas H. (Colonel) Logan, Richard, Jr. (Captain) Taliaferro, William T. (Lieutenant) Carrington, Henry A. (Colonel) Macon, Miles C. (Captain) Terry, William R. (Colonel) Chamberlain, George (Captain) Mahone, William (General) Turner, Thomas, T. (Lieutenant) Coleman, Henry E. (Colonel) Marshall, James K. (Colonel) Walker, James A. (General) Darden, James D. (Captain) Mayo, Joseph M. (Colonel) Walker, Reuben L. (Colonel) Edmonds, Edward C. (Colonel) Mayo, Robert M. (Colonel) Walthall, James A. (Lieutenant) Ellis, John T. (Colonel) McCulloch, Robert (Captain) Ward, John C. (Captain) Eyster, George H. (Captain) Munford, Thomas T. (Colonel) Watson, John D. (Captain) Flowerree, Charles C. (Colonel) Moore, Charles W. (Lieutenant) Wharton, Richard G. (Lieutenant) Fry, William T. (Captain) Morrison, Joseph G. (Lieutenant) Whiting, Henry A. (Major) Gantt, Henry (Colonel) Niemeyer, John C. (Lieutenant) Williams, Lewis (Colonel) Gilliam, Joseph S. (Lieutenant) Norton, George F. (Captain) Williamson, William G. (Lieutenant) Griggs, George K. (Captain) Otey, Kirkwood (Major) Wingfield, John S. (Lieutenant) Grigsby, Benjamin P. (Lieutenant) Paxton, James G. (Major) Wilson, Nathaniel C. (Major) In addition, Abner C. Beckham served as a volunteer aide-de-camp to General James Kemper, Rodes, Virginius H. Rodes served as a volunteer aide-de-camp to General Robert Rodes (his brother), and that James D. Hunter served with the rank of “cadet” at General Robert E. Lee’s headquarters. It is my understanding that this rank of “cadet” allowed very young men to serve in a sense as “apprentices” on the staffs of generals.

It should also be noted that Colonel Birkett D. Fry of the 13th Alabama Infantry Regiment (in General James Archer’s Brigade) attended but did not graduate from VMI, as was also the case of Major Walter H. Taylor of General Robert E. Lee's staff (in the book "Lee's Adjutant: the Wartime Letters of Colonel Walter Herron Taylor", it says Taylor was forced to drop out after two years upon the death of his father but was later made an honorary member). Colonel William H. F. Payne of the 2nd North Carolina Cavalry Regiment (who was captured on June 30 during the Battle of Hanover), did not graduate from VMI but was also later made an honorary member. (My sincere thanks to Michael King for his extensive research on this interesting topic !!!)

The other railroad cutsAny student of the battle is well aware of the famous “railroad cut” north of the Chambersburg Pike, but little is mentioned of the importance of two other “cuts” which played a role in the hard-fought action on the morning and afternoon of July 1. The well-known railroad cut is actually the center cut, and is the area where the 6th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment, part of General Solomon Meredith’s First Brigade (“The Iron Brigade”) of General James S. Wadsworth’s First Division of the Union I Corps, along with the 95th New York Infantry Regiment and the 14th Brooklyn Infantry Regiment (also known as the 84th New York Infantry Regiment) of General Lysander Cutler’s Second Brigade of that division, attacked northward across the Chambersburg Pike and routed the 2nd Mississippi Infantry Regiment and the 42nd Mississippi Infantry Regiment, two of the four regiments of General Joseph R. Davis’ Brigade of General Henry Heth’s Division of General A. P. Hill’s III Corps. The Union attack resulted in the capture of more than 200 Confederate soldiers who had taken cover in the railroad cut:

(view from the eastern cut looking west toward the center cut)The western cut, located roughly 250 yards west of the center cut, is the area where the 149th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, one of the three regiments in Colonel Roy Stone’s Second Brigade of General Thomas A. Rowley’s Third Division of the Union I Corps, used the northern lip of the cut as a firing platform to inflict damage on the 45th North Carolina Infantry Regiment and the 2nd North Carolina Infantry Battalion, two of the five units in General Junius Daniel’s Brigade of General Robert E. Rodes’ Division in General Richard S. Ewell’s II Corps, as they advanced as the right flank of the brigade in their assault on Union troops on Oak Ridge. After soon being forced out of the cut by Confederate artillery fire, the 149th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment later made a charge and forced the 45th North Carolina Infantry Regiment and the 2nd North Carolina Infantry Battalion out of the same railroad cut which they occupied after that Union regiment had been forced to withdraw:

(view of the western cut from the southeast)

north side of the center cut)

(view of the western cut looking west)

(view of the north side of the western cut)

The eastern cut, located roughly 275 yards east of the center cut, is the area where the remnants of the 16th Maine Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel Charles W. Tilden surrendered on the afternoon of July 1 after being sacrificed to serve as a “rear guard” for the rest of their brigade (General Gabriel R. Paul’s First Brigade of General John C. Robinson’s Second Division of the Union I Corps) and allow their fellow soldiers to retreat toward town and Cemetery Hill. An interesting and often overlooked fact is that the soldiers of the 16th Maine Infantry Regiment tore their flag into pieces and hid the shreds among themselves in order to keep it from falling into Confederate hands (see the “Miscellaneous small markers” section on my “Off the Usual Path” page):

(view from the east end of the center cut

looking toward the eastern cut)

(view of the eastern cut looking east toward town)

Flank markers

Flank markers are commonplace on the battlefield but are often overlooked despite their importance for those studying the movement and positions of a particular regiment. In addition to their importance, they are also interesting in themselves. While it is understandable that most (but not all) infantry regiments would have flank markers, some (but not all) batteries have them as well. In addition, despite the fact that the positions of cavalry units were obviously more fluid, some (but not all) cavalry units also have flank markers. It is important to note that not all flank markers mark the exact location of a unit's flanks due to the sheer distances involved (for example, normal spacing between cannons on the firing line was roughly 14 yards, and Union batteries normally had 6 cannons).

Among other things, the size, shape, amount of inscription and detail, and height above the ground of flank markers also varies. Generally speaking, though, there does appear to be two most common shapes: the square marker with the flat top and the square marker with the pointed top:

Examples of just a few of the other shapes include those of the 137th New York Infantry Regiment on Culp's Hill (see the photo below on the left) and those of the 12th New Hampshire Infantry Regiment on the east side of the Emmitsburg Road (see the photo below on the right):

In addition, the flank markers for Massachusetts infantry regiments are larger and with a more rectangular shape that includes a pointed top:

Perhaps the most unusual shape for flank markers has to be those that are in the shape of a tree stump for the 90th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment (see the "Unusual monuments" section on my "Something Different" page):

In regard to the amount of inscription and detail, some simply have initials such as "LF" or "L.F." or "LEFT FLANK" or "LEFT" while others also identify which regiment and occasionally have their Union Corps symbol as well:

I know of at least one set of flank markers, those of the 14th Indiana Infantry Regiment on East Cemetery Hill along the west side of Wainwright Avenue, that includes brief text as well:

What is also interesting is that the monument to the 14th Indiana Infantry Regiment is nowhere near the flank markers and is located about 100 yards to the west and up on the crest of East Cemetery Hill near the equestrian monument to General Winfield S. Hancock. The left flank marker is to the north of the monument to the 153rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment and the right flank marker is to the south of the monument to the 41st New York Infantry Regiment.

The reason for this is that the 14th Indiana Infantry Regiment and other regiments of their brigade commanded by Colonel Samuel S. Carroll in the Union II Corps were rushed over from their positions on Cemetery Ridge to help repulse the Confederate attack by troops commanded by General Harry T. Hays and Colonel Isaac E. Avery on East Cemetery Hill on the evening of July 2. These flank markers indicate the regiment’s furthermost point reached in their counterattack as well as indicating the position where they remained for the remainder of the battle. The monument to the 14th Indiana Infantry Regiment was originally placed between the flank markers but later moved to its original “line of battle” position on the crest of East Cemetery Hill with monuments of their “sister” regiments.The height above the ground of the flank markers also varies, sometimes even of those to the same regiment, as in the case of those of the 23rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment on the left side of Slocum Avenue as you head up Culp's Hill:

I know of two regiments that have a third flank marker in addition to the standard left flank and right flank markers. The 13th New Jersey Infantry Regiment, whose monument is located southeast of Spangler's Spring south of Culp's Hill along the west side of Carmen Avenue, has a left center flank marker located roughly 30 yards north of the monument and on the other side of the road:

Another regiment with a third flank marker is the 15th New Jersey Infantry Regiment, who does not have their own monument but is commemorated by the monument to the First New Jersey Brigade, located roughly 65 yards off to the east side of Sedgwick Avenue south of the intersection with United States Avenue (see the "Faces of the battle" section on my "Something Different" page). There is a right center flank marker located roughly 60 yards north of the monument and on the east side of a "T" stone wall, and it also serves as the right flank marker for the 2nd New Jersey Infantry Regiment (if you look carefully, the "15" may appear to be a "16", but that is due to the aging/chipping of the marker:

This brings us to the subject of "shared" flank markers, and I know of several others, including the one nearby along the south side of the stone wall that serves as the left flank marker for the 1st New Jersey Infantry Regiment and as the right flank marker for the 15th New Jersey Infantry Regiment (as mentioned above, if you look carefully, the "15" may appear to be a "16", but that is due to the aging/chipping of the marker):

Also nearby along the south side of the same stone wall is the one that serves as the left flank marker for the 2nd New Jersey Regiment and as the right flank marker for the 3rd New Jersey Infantry Regiment:

Several New York regiments also "share" flank markers, such as the one on Cemetery Ridge along the east side of Hancock Avenue about 100 yards north of The Angle. This one serves as the left flank marker for the 125th New York Infantry Regiment and as the right flank marker for the 39th New York Infantry Regiment:

Another example is that of the one on East Cemetery Hill along the west side of Wainwright Avenue that serves as the left flank marker for the 68th New York Infantry Regiment and as the right flank marker for the 54th New York Infantry Regiment:

Other "shared" flank markers occur between regiments from different states, such as the one for the 147th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment and the 5th Ohio Infantry Regiment roughly 20 yards south of the monument to the 147th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment (see the photo below on the left) in the southwest corner of the intersection of Wheatfield Road and Sykes Avenue just north of Little Round Top. The inscription for the 5th Ohio Infantry Regiment is clearly visible on the south side of the marker, but you have go around to the back to the west side to see the inscription for the 147th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment (see the photo below on the right):

What is also interesting is that neither side of the marker indicates whether it was the right flank or the left flank of that regiment, and that the other flank marker for the 147th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment located roughly 10 yards north of the monument also has no inscription as to which flank it was. Perhaps the surviving veterans felt it was simply understood which was which ???

Another example is the one west of the Wheatfield just north of the Loop on Sickles Avenue and is located roughly 30 yards off the road about halfway between the monument to the 1st Michigan Infantry Regiment and the monument to the 118th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment. Both regiments have their own left flank and right flank markers nearby as well as this "shared" marker:

Looking for flank markers can often be perplexing, since some of them have disappeared over time due to being damaged by storms, accidents, or being removed due to road widening or other reasons. In some instances, a regimental monument itself may represent the position of one of the flanks. One such monument is the monument to the 68th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment located along the north side of the Wheatfield Road across from the Peach Orchard. The inscription that is on the front of the monument reads "THIS MONUMENT MARKS THE LEFT OF THE REGIMENT WHILE SUPPORTING CLARK'S BATTERY JULY 2, 1863":

There is a similar monument but interestingly enough, it marks the position of not the left or right flank but of the left center of a regiment. The monument to the 14th Connecticut Infantry Regiment, located on Cemetery Ridge along the west side of Hancock Avenue across the road from the equestrian monument to General George G. Meade, contains an inscription on its south side that reads "LEFT CENTRE OF REGT.":

Another similar monument is the monument to the 28th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment (also featured further above on this page) located on the western edge of the Wheatfield on the south side of the upper portion of the loop on Sickles Avenue. The words “RIGHT FLANK” are inscribed at the bottom of the monument, and yet there is also a small “Right Flank” marker only a few feet away:

Located south of the Wheatfield in the southeast corner of the intersection of Sickles Avenue and Ayres Avenue is the monument to the 5th New Hampshire Infantry Regiment; the left flank marker located roughly 60 yards directly south of the monument is “ALL LEFT”:

There is a set of flank markers that are interesting for an entirely different and unusual reason. The monument and the flank markers for the 8th New York Cavalry Regiment are located on McPherson's Ridge along the east side of Reynolds Avenue and just south of the Chambersburg Pike. However, if you look closely, you will notice that the monument in the middle of the flank markers is not that of the 8th New York Cavalry Regiment but that of the 8th Illinois Cavalry Regiment ---- the monument to the 8th New York Cavalry Regiment was originally placed in the wrong position and was later moved approximately .2 of a mile further south, but the flank markers were never moved or removed:

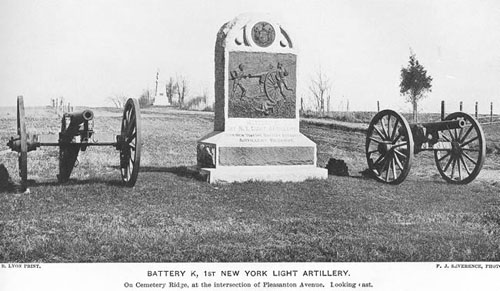

Another set of interesting and confusing flank markers are those of Captain Robert H. Fitzhugh's Battery K, 1st New York Light Artillery. The monument was originally located near the northeast corner of Hancock and Pleasonton Avenues, but was later moved around 1903 approximately .4 of a mile to the north roughly 100 yards north of The Angle on the east side of Hancock Avenue. The flank markers, however, still remain at their original positions on either side of Pleasonton Avenue:

(Image from the “Final Report on the Battlefield of Gettysburg by the New York

Monuments Commission for the Battlefields of Gettysburg and Chattanooga”)It is my understanding that Captain Fitzhugh personally paid for the relocation of the monument once it was acknowledged to be in the wrong position. I wonder why they didn't bother to move the flank markers ???

There is at least one flank marker that has its own unique mystery --- it is completely blank !!! Located right along the west side of the Emmitsburg Road in front of the Joseph Sherfy house and roughly 15 yards north of the monument to the 114th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, one could make an argument that it must be the right flank marker for that regiment, but I have yet to find a corresponding left flank marker near the monument, marked or unmarked, on that side of the road -- the monument to the 57th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment just to the north has both their flank markers, and the clearly marked left flank marker a short distance to the north on the east side of the road is understood to be for the monument to the 105th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment. So therein lies the mystery --- it sure looks like a flank marker, but for which regiment and why is it blank ???

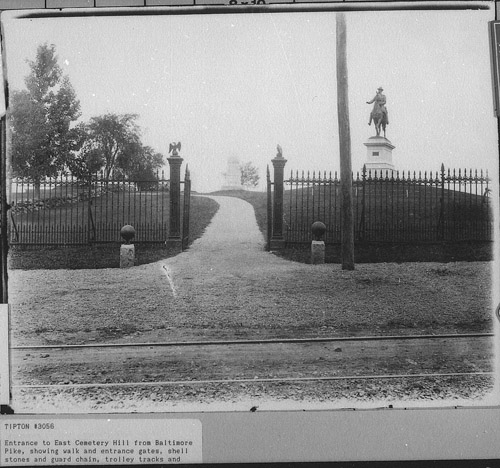

Then there are the flank markers for the 84th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, located on either side of the monument along the south side of Pleasonton Avenue on Cemetery Ridge. The only problem is, the regiment was never on the battlefield but was guarding their division's supply trains in Westminster, Maryland (see the "The monument (and flank markers) to the regiment that wasn’t there" section on this page). And finally, there are the small stone bases that appear to be flank markers but aren't flank markers at all. Located on East Cemetery Hill right along the east side of the Baltimore Pike directly across from the entrance to the Evergreen Cemetery are six small stone bases for the cannonball and chain fencing during much earlier times and used in various areas of the park to delineate roadways from Park land like a curbstone would today:

(Photo courtesy of the GNMP and Steve Floyd)So, while it is always important and interesting to look at and learn from the monuments on the battlefield, perhaps you will take the time to investigate the nearby flank markers -- they are important and interesting in their own right !!!

Chasseurs and ZouavesWhile Civil War buffs are familiar with Zouave regiments, there was also another type of French-inspired military unit with similar looking uniforms, the Chasseurs, and four Union regiments with such a designation participated in the Battle of Gettysburg. They were the 65th New York Infantry Regiment, the 84th New York Infantry Regiment (also known as the 14th Brooklyn Infantry Regiment), the 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, and the 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment (and which is sometimes mistakenly referred to as a Zouave regiment). Of these regiments, only the 84th New York Infantry Regiment (14th Brooklyn Infantry Regiment) was still wearing their uniquely designed Chasseur uniforms by the time of the Battle of Gettysburg. The others had discarded the Chasseur uniforms, most of which had come from France as a gift to the Federal government, due to sizing and fitting difficulties.

Only one Union regimental monument, however, actually has the word “Chasseurs” (the French word, in essence, for “Light Infantry”) inscribed on it -- the monument to the 65th New York Infantry Regiment located on Culp’s Hill about one-half of the way up from Spangler’s Spring on the left side of Slocum Avenue roughly 100 yards past the statue of General John W. Geary:

There were ten Union Zouave regiments that participated in the Battle of Gettysburg: the 10th New York Infantry Regiment, the 41st New York Infantry Regiment, the 44th New York Infantry Regiment, the 73rd New York Infantry Regiment, the 146th New York Infantry Regiment, the 23rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, the 72nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, the 95th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, the 114th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, and the 155th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment (which did not become a Zouave regiment until 1864).

Many of the regiments had discarded all or most of their colorful Zouave uniforms by the summer of 1863 for the standard Union uniform, but generally speaking, three regiments did appear in full Zouave or Zouave-inspired uniforms at the Battle of Gettysburg: the 84th New York Infantry Regiment (14th Brooklyn Infantry Regiment), the 146th New York Infantry Regiment, and the 114th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, while a few others wore a “mix” (like the 95th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, which had retained only the Zouave jacket). Of course, there were no doubt exceptions to the rule in each and every regiment.

On the Confederate side, the “Louisiana Tigers” of General Harry T. Hays’ Brigade in General Jubal A. Early’s Division of General Richard S. Ewell’s II Corps is often mistakenly believed that they wore Zouave uniforms at the Battle of Gettysburg, but that was not the case although the original “Louisiana Tigers” of Major Chatham R. Wheat’s Battalion did wear them earlier in the war. (A personal note: my sincere thanks to NPS Park Ranger/Historian John Heiser for his assistance and detailed information provided for this interesting topic of Chasseurs and Zouaves -- thank you very much, John !!!)

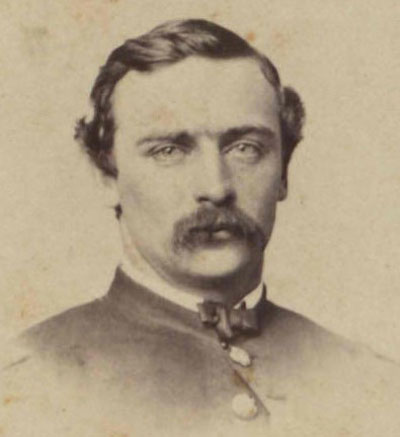

VivandieresA vivandiere (or vivandere) was a combination nurse, cook, seamstress, and laundress who travelled with the Zouaves. Vivandieres appeared in European armies, especially in France, as women who were part of a regiment and provided the sale of spirits and other comforts, and attended to the sick. The women were known to wear the uniform of the regiment. Generally speaking, a vivandiere adopted the style of clothing of her regiment, but with men's pants under a knee-length skirt and usually carried a cask (slung over a shoulder) which was generally filled with water, wine, or brandy. Most vivandieres were sent home when the heavy fighting started, but there was at least one exception at the Battle of Gettysburg: Marie Brose Tepe of the 114th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment (“Collis’ Zouaves”).

Also known as “French Mary”, she is considered the only enlisted woman at Gettysburg, where she carried water and treated the wounded during the heaviest of the fighting. She was in 13 battles, and carried a .44 caliber pistol. From the book “Women at Gettysburg" by E. J. Conklin, “When the regiment was not in action, she cooked, washed, mended for the men. She drew the pay of a soldier and was allowed 25 cents per day extra for hospital and headquarters services, maker her pay $21.45 per month for over two years. Then some friction in the Paymaster's Department about the enlistment of women stopped her pay, but did not dampen her patriotism."

For several weeks following the Battle of Gettysburg, “French Mary” served as a nurse in a field hospital located on the Taneytown Road. She then went back to her regiment, and it is believed that “French Mary” was still with the 114th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment in Washington, D.C. for the Grand Review of the Union Army held on May 23, 1865, followed by the mustering out of the regiment a few days later.

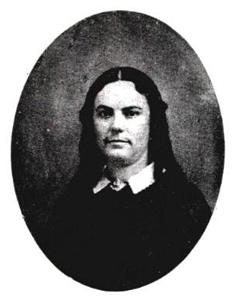

(1863 photo of “French Mary” Tepe by the Tyson Brothers Studio in Gettysburg)

A grave topic

While not specifically tied to the Battle of Gettysburg, two fellow members of the York Civil War Roundtable pointed out to me in 2009 an interesting G.A.R. grave marker at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Hanover, Pennsylvania. While I was well aware of the more common G.A.R. marker in the shape of a five-pointed star (shown in the photo below on the left), I had never seen one in the shape of a Civil War canteen (shown in the photo below on the right):

Another canteen-shaped marker was found by those same members in the Red Mount United Methodist Church cemetery near East Berlin, Pennsylvania, as well as other similar canteen-shaped markers that they found in March of 2010 in Fairview Cemetery in Wrightsville, Pennsylvania, that contained the name of the G.A.R. Post:

I also discovered other variations of the G.A.R. five-pointed star and other interesting markers at http://www.usgwarchives.net/pa/1pa/tscarvers/veteran-markers/veteran-markers-civil-war.htm, which also included photographs of two types of Confederate markers, one of which is shown in the photo below at the grave of General Lafayette McLaws located in Laurel Grove Cemetery in Savannah, Georgia:

(Photo courtesy of Ed Doadt)The most interesting grave marker I have seen so far was also one that my two fellow members of the York Civil War Roundtable discovered in Fairview Cemetery:

Sergeant Charles D. Marquette was a member of the 93rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment (see the “The monument with two bases” section on my “More Odds and Ends” page) and is listed on the Pennsylvania Monument (spelled as “CHAS MARQUETT”) as being on the regimental roster at Gettysburg; he was awarded the Medal of Honor for gallantry in action at the Battle of Petersburg in April of 1865.

Here is a photo submitted by Mark Leik of a different type of G.A.R. grave marker at the John McGarah Post 132 in Portland, Michigan:

I am continuing my research on Civil War grave markers, and if anyone else has also seen these canteen-shaped markers or any other different style Civil War grave marker, please email me at randydrais@gmail.com. Thanks !!!

An Australian in Pickett’s Charge?As all Civil War buffs know, the ranks of both armies were comprised of not only American-born citizens (and occasionally Native American Indians as well) but also hundreds of thousands of immigrants from many, many nations (I have read of estimates of approximately 500,000 foreign-born soldiers in the Union Army and approximately 100,000 foreign-born soldiers in the Confederate Army).

The largest groups were from Germany, Ireland, and England, but there were soldiers from a multitude of other countries, including Canada, Italy, France, Scotland, Russia, Hungary, Finland, Sweden, Switzerland, Spain, and Portugal. In fact, the 39th New York Infantry Regiment (also known as the “Garibaldi Guards”) was originally comprised of three German Companies, three Hungarian Companies, one Italian Company, one Swiss Company, one French Company, and one Company of Spaniards and Portuguese. The Spanish/Portuguese Company also had individuals from Cuba, Nicaragua and Chile.

According to Civil War historian/author Thomas L. Elmore (who graciously allowed me to share the following information), approximately 28,000 Union troops (roughly one out of every four soldiers) and about 3,500 Confederate troops at Gettysburg were born in another country. Here are just a few of his examples:Private Richard Flanagan (72nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment) -- Australia

Private Albert Oss (11th New Jersey Infantry Regiment) -- Belgium

Assistant Adjutant General Francis L. Price (to General Jerome Robertson) -- Ceylon (Sri Lanka)

Lieutenant Colonel Federico Fernandez Cavada (114th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment) -- Cuba

Private George D. Lustin (15th Louisiana Infantry Regiment) -- Indonesia or India

Private Jose Antonio Candida (10th Louisiana Infantry Regiment) -- Mexico

Private Thomas R. Morris (15th Alabama Infantry Regiment) -- New Zealand

Private Nichole Danilovich (10th Louisiana Infantry Regiment) -- Russia

First Sergeant George T. Chase (2nd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment) -- South AfricaIn addition, Chinese immigrants served in the Union Navy, and some researchers estimate that approximately 50 served in the Union Army with at least a few serving in the Confederate Army. At least two Chinese soldiers (who often adopted American names) who fought at the Battle of Gettysburg were Private Joseph L. Pierce of the 14th Connecticut Infantry Regiment and Corporal John Tommy/Tomny/Tomney of the 70th New York Infantry Regiment (who lost both legs in the fighting on July 2 and eventually died of his wounds).

Which brings us to the question: was there an Australian in Pickett’s Charge? Private William Mitchel of the 1st Virginia Infantry Regiment was one of the many soldiers killed during Pickett’s Charge. One of three sons born to Irish patriot John Mitchel, who had been exiled to Tasmania, Australia, by the British government around 1850, William lived there with his family until they all escaped by ship with several other exiles, eventually arriving in New York City in 1853. When the Civil War broke out, John moved his family to Richmond, Virginia, working as a newspaper editor and served in the Ambulance Corps. All of the sons enlisted in the Confederate Army: John Jr. enlisted in the 1st South Carolina Permanent (Light) Artillery, and James and William enlisted in the 1st Virginia Infantry Regiment.

Private William Mitchel was hastily buried by his comrades on the Nicholas Codori farm with his name on a piece of paper fastened to a piece of board to mark his grave. Sadly, the Codori family did not bother to maintain any of the grave markers on the farm, and Private Mitchel’s remains were disinterred with others in 1872 and sent in the second shipment to Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond. Private William Mitchel, of Ireland and Australia, is interred in the Gettysburg section of that cemetery as an “Unknown” !!! (A personal note: my sincere thanks to NPS Park Ranger/Historian John Heiser for his assistance and detailed information provided regarding Private William Mitchel -- thank you very much, John !!!)

The other GettysburgsIn addition to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, there are two other Gettysburgs in the United States. One of them is Gettysburg, Ohio, with a current population of approximately 500 people. Located in Darke County, the village of Gettysburg was founded by natives of Adams County, Pennsylvania in the late 1820’s and officially adopted its now-famous name in 1842.

The other municipality is Gettysburg, South Dakota, with a current population of approximately 1,000 people. Located in Potter County, its nickname is “Where the Battle Wasn’t”, but it does have a strong connection to that Civil War battle.

In early 1883, a joint stock company was formed to establish a colony for Civil War veterans in Potter County, South Dakota (at that time, it was the Dakota Territory). The first permanent settlers arrived on May 21, 1883, including veterans O. L. Mann, J. Q. Walker, J. B. Weeks, James Bryson, K. W. Pearce, Asheal Todd, and several others.

The first choice for the name of the new town was “Meade”, but it was rejected by the United States Post Office Department due presumably to another town with or applying for the same name; the second choice, which has long since been forgotten, was also rejected.

The third choice, “Gettysburg”, was suggested by former Captain John W. Kennedy of the 134th New York Infantry Regiment, who had fought at Gettysburg. A review of historical records provided by the Dakota Sunset Museum of Gettysburg, South Dakota includes the following settlers of that town and/or county of former Union Army soldiers (or their relatives) whose regiments saw action at the Battle of Gettysburg:

Christopher Baum 5th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment Menzo Benster 24th Michigan Infantry Regiment George Carver 5th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment Charles Dean 20th Indiana Infantry Regiment Edward Dreblow 3rd and 26th Wisconsin Infantry Regiments Nicholas Frankhauser 8th Ohio Infantry Regiment David Goodnow 8th New Jersey Infantry Regiment James Griffith 140th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment George Hammel 15th U.S. Infantry Regiment and 43rd New York Infantry Regiment Benjamin Hart 2nd Wisconsin Infantry Regiment Hudson Jack 3rd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment Elpinston Kent 8th Illinois Cavalry Regiment Almond McLaughlin 1st Minnesota Infantry Regiment Conrad Miller 55th Ohio Infantry Regiment Albert Moulton 37th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment Andrew Murdy 1st West Virginia Cavalry Regiment Amos Newland* 17th U.S. Infantry Regiment James Rodenhurst 146th New York Infantry Regiment Moses Slawso 107th New York Infantry Regiment James Som(m)erville 5th New Jersey Infantry Regiment William Trumbull 65th New York Infantry Regiment David Warner 134th New York Infantry Regiment Frederick Warner 7th Ohio Infantry Regiment Charles Welch 19th Indiana Infantry Regiment William Whitford 5th Michigan Cavalry Regiment William Wright 12th Illinois Cavalry Regiment Frank Young 6th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment *killed at the Battle of Gettysburg on July 2, 1863 Eventually, roughly 180 Union Army veterans settled in Potter County, home of Gettysburg, South Dakota. The historical records also indicate approximately 70 Confederate Army veterans settled in South Dakota, but none in the town of Gettysburg. One wonders if the name of the town was the reason, doesn’t it? A final note about Captain John W. Kennedy, who died there in 1918: on his tombstone, the following phrase is carved --- “He fought at Gettysburg and he died at Gettysburg” !!!

“Those damned wagons …”One of the many controversies surrounding the Battle of Gettysburg involves, of all things, captured Union supply wagons. As most Civil War history buffs know, as Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart moved behind Union lines on his way north to link up with General Richard S. Ewell’s II Corps, he encountered an opportunity on June 28 near Rockville, Maryland to attack and/or capture a large Union supply train consisting of 150 wagons. Knowing that one of his military objectives was to collect provisions along with information, Stuart attacked and captured 125 of the 150 Union supply wagons (25 were damaged and/or destroyed). There is no doubt that bringing those wagons with him slowed General Stuart’s cavalry as they advanced northward, but how much of a role this decision played in causing the Confederate Army to lose the Battle of Gettysburg is debated to this very day.

What is overlooked is the interesting fact that these wagons were possibly made by wagon makers John, Henry and Clem Studebaker, who were born just 3 miles north of Hunterstown, which is roughly 7 miles north of Gettysburg. Their father began building carriages and wagons in 1830 in his nearby shop and later moved his family to South Bend, Indiana. His sons carried on the family tradition, forming H. & C. Studebaker in 1852. The company was one of the businesses with contracts with the U.S. government to build wagons and other equipment during the Civil War. I believe I read somewhere that over 600,000 Union wagons were built by all the contractors combined --- what are the odds that those 125 wagons would be captured and then perhaps travel past the very area where the wagon makers were born? That would be a truly ironic example, both figuratively and literally, of “what goes around, comes around …”

A tale of two spiesDuring the early morning hours of June 28, 1863, Union General George Gordon Meade was appointed commander of the Army of the Potomac while at his corps headquarters near Frederick, Maryland. Later that same day, a spy brought news about the location of Meade's army to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, a distance of fifty miles, where Confederate General Robert E. Lee and General James Longstreet were headquartered. Based solely on that information, Lee ordered his dispersed army to move immediately toward a small crossroads town in south-central Pennsylvania. Thus was the beginning of the historic three-day battle known as Gettysburg.

That spy was Henry T. (Thomas) Harrison, whose full identity was not known until 1986 when historian James O. Hall uncovered information in the Civil War records at the National Archives. Later research by Mr. Hall proved conclusively that Harrison did appear on stage in Richmond on a bet but he was anything but a professional actor. Born near Nashville, Tennessee in 1832, Harrison joined the 12th Mississippi Infantry Regiment in the spring of 1861 as a private, but in November of 1861 he was discharged and eventually became a Confederate spy. Eventually assigned to General Longstreet in March of 1863, Harrison was dispatched to spy for General D.H. Hill in North Carolina and captured by Union soldiers but eventually convinced his captors that he was an innocent civilian avoiding conscription. Reporting back to General Longstreet in April of 1863, Harrison performed his duty admirably as a spy which culminated in his now-famous report on June 28 that so dramatically affected the Gettysburg Campaign.

Released from duty in September of 1863, Harrison soon married Laura Broders in, of all places, Washington, D.C., and after traveling to New York for their honeymoon, he continued his espionage activities in Washington, D.C. and New York for the remainder of the war, dying in 1923 in Covington, Kentucky at the age of 91.