Battle of Gettysburg Buff

A website for Civil War

buffs interested in the

Battle of Gettysburg

Odds and Ends

I hope you will find the topics and information on this page interesting and informative:

Cannons, Cora, and PenelopeApproximately 653 cannons were assigned to the two armies (372 to the Union Army and 281 to the Confederate Army) in the Gettysburg Campaign, and that today there are approximately 370 cannons that sit on the battlefield that had been placed by the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association. This total does not include the 14 upright cannon tubes which mark the location of the headquarters of the major generals, nor does it take into account the many others requested and received from the War Department that were melted down into the bronze equestrian statues and other bronze markers.

It is important to know that due to a comprehensive, costly, and time-consuming restoration process begun in 2000 as a joint effort between the National Park Service and volunteers from the Friends of the National Parks at Gettysburg, about 135 cannons are still off the field. The good news is that all of the ones you now see have been restored, and no more have to be temporarily removed.

Only 1 cannon can be officially documented as having actually seen action at Gettysburg, and that is "Cannon Number 233" of Lieutenant John Calef's Battery A, 2nd U.S. Artillery, which fired the first Union artillery shot of the battle while under the command of General John Buford's Cavalry Division on McPherson's Ridge on July 1:

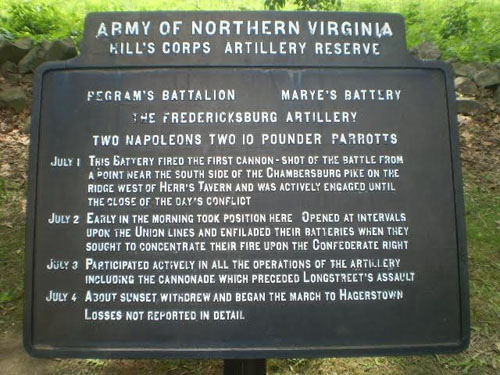

It should be noted that while there is no similar cannon indicating the first Confederate artillery shot fired at Gettysburg, the artillery battery that did so, Captain Edward Marye’s Battery of Major William Pegram’s Artillery Battalion, is acknowledged accordingly on its marker on Seminary Ridge along the east side of West Confederate Avenue just south of McMillan’s Woods:

An interesting and lesser known fact about the cannons on the battlefield is that one of them was manufactured in 1866 and never fired a shot during the Civil War at all. I was not aware of this until I recently read the excellently written and highly informative book by George W. Newton entitled "Silent Sentinels: A Reference Guide to the Artillery at Gettysburg" (listed on my "Books Worth Reading" page). Located on East Cemetery Hill only a short distance south of the fine equestrian monument to Union General Winfield S. Hancock, look for the small monument to Cooper's Battery of the 1st Pennsylvania Artillery. Find the cannon with the number "931" at the top of the muzzle and "1866" on the middle-lower right side of the muzzle:

Two other interesting cannons are one named "Cora" (located along the north side of United States Avenue at the Abraham Trostle farm adjacent to the monument to Captain John Bigelow's 9th Massachusetts Light Artillery Battery of the Artillery Reserve):

and a dented cannon at Lieutenant Chandler Eakin's Battery H of the 1st U.S. Artillery located in the Soldiers' National Cemetery along the fence separating it from Evergreen Cemetery:

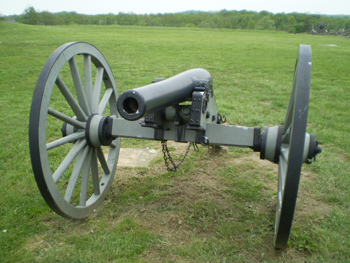

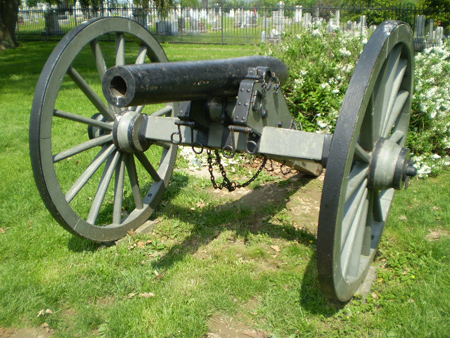

Generally speaking, there were three major types of cannons (or artillery pieces as they are called) -- the 12-pounder (bronze) Napoleon, the 3-inch (iron) Ordnance rifle, and the 10-pounder (iron) Parrott rifle. There were also a few of the 20-pounder Parrott rifles that are distinguished by the much larger breech (as seen in the bottom right photo):

(Union 12-pounder Napoleon)

(Confederate 12-pounder Napoleon)

(3-inch Ordnance)

(10-pounder Parrott)

(20-pounder Parrott)

It should be noted that two Confederate batteries had Navy Parrotts: Captain John T. Wingfield’s Battery and Captain Hugh M. Ross’s Battery, both of which were in Major John Lane’s Artillery Battalion:

There were also other types of cannons used by the Confederate Army, including a 6-pounder bronze cannon (see the top two photos below) and a 12-pounder howitzer (see the bottom two photos below) at Captain A. C. Latham's Battery in General John B. Hood's Division on South Confederate Avenue:

The Confederate Army also utilized foreign-made cannons, including 2 British Whitworth breech-loading cannons on Oak Hill at Captain W. B. Hurt's Battery of the Artillery Reserve:

and four Austrian 24-pounder howitzers with their unique "handles" on West Confederate Avenue at Captain George V. Moody's Battery of the Artillery Reserves:

What is perhaps not common knowledge is that there are 70 cannon "replicas" (36 10-pounder Parrott rifles, 18 3-inch Ordnance rifles, and 1 20-pounder Parrott rifle) on the battlefield that can be spotted if you look closely at them. There are also 15 "false Napoleons" --- 6-pounder cannons that were modified to appear like the 12-pounder Napoleons.

Generally speaking, the replicas do not have the manufacturing information on the muzzle, the tubes are not always quite tapered the same, or other details are missing (like the initials "U.S." on the top of the tube of the Union cannons --- and remember, the Confederate Army also had captured Union cannons which they used). One example can be found in the Soldiers' National Cemetery near the memorial to the Gettysburg Address. One of the cannons located at the monument to the 1st Massachusetts Light Artillery is a replica:

My favorite cannon on the battlefield, though, is nearby (it is located just inside the Baltimore Pike entrance to the Soldiers' National Cemetery and roughly 100 yards to the south of the fine statue of Union General John F. Reynolds), and it is actually an extremely detailed scale model that sits atop the monument to Captain Elijah D. Taft's Fifth New York Independent Battery:

It should also be noted that there are two cannon tubes of Union 24-pounder iron howitzers that were incorporated as part of the "High Water Mark" monument area on Cemetery Ridge:

In addition, if you look at the left photo above, you can see two “pyramids” of cannon balls at the cannons (there are two slightly larger “pyramids” behind the High Water Mark “book” as well). Other ammunition “pyramids” used to be prevalent at most (if not all) of the artillery pieces that were placed throughout the battlefield, and were of two types: cannon balls or canister-like cylinders. The pyramids were removed over time, mostly when the National Park Service restoration program of the cannons began in 2000, although there are a few that can still be found, so keep your eyes open for them !!!

Of course, any section about cannons at Gettysburg would not be complete without mentioning

"Penelope," the ancient cannon fired after Democratic election victories until 1855 when its tube ruptured after such a celebration. Its final resting place is located outside the former office of the Compiler newspaper at 126 Baltimore Street:

(William H. Tipton photo circa 1895)To learn more about the cannons at Gettysburg, I highly recommend reading the great book that I mentioned earlier in this section, "Silent Sentinels: A Reference Guide to the Artillery at Gettysburg," by George W. Newton. You will be glad you did.

The cannons on the battlefield todayAfter the Gettysburg National Military Park was created by federal legislation in 1895, the decision was made to have the cannon tubes on the battlefield placed onto replicas of the original carriages. Bids were advertised for manufacturers to not only provide these reproduction carriages but also for tablets, markers, and signs for the park. Calvin Gilbert, who owned a metal foundry in Gettysburg and was a Gettysburg native, was one of the first to offer a bid for this extensive project. Between 1895 and 1913, his foundry produced well over 250 carriages and more than 200 iron tablets for battery positions, avenue signs, and farm signs as well as a variety of other markers.

Calvin Gilbert was also a Union veteran who enlisted on September 25, 1861 as a Private in Company F of the 87th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment. He transferred to the regimental band in October of 1861 but was discharged when Congress ended funding for regimental bands. Gilbert soon enlisted in Company K of the 1st Pennsylvania Reserves and served as a drummer for the regiment during the Battle of Gettysburg (see the “Skirmish lines and smaller units” section on my “Off The Usual Path” page). Calvin Gilbert died on September 13, 1939 and is buried in Evergreen Cemetery, but his legacy is seen everywhere on the battlefield.

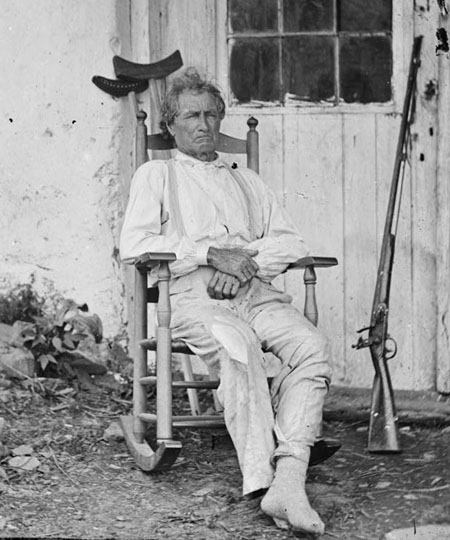

The other "citizen soldier" at GettysburgI think it would be safe to say that everyone who ever visited the battlefield eventually learned about John Burns, the Gettysburg resident and War of 1812 veteran who, despite being over 70 years old, took up arms with the 150th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment against the oncoming Confederate Army on July 1. However, I would venture a guess that very few people know that there was another "citizen soldier" at Gettysburg on that very day in 1863 as well.

A boyish-looking young man, whom soldiers in the 12th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment estimated to be no more than 16 years old, had encountered the regiment about 2 miles north of Emmitsburg on June 30, 1863 and expressed his desire to join in the fight. The young man was given a uniform and rifle, and was wounded twice the next day on Oak Ridge. Left behind during the regiment's eventual retreat to Cemetery Hill, his identity remained a mystery for many years due partly because of the fact that he was not officially mustered into service.

Years later in 1886, an article appeared in the Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine that provided a firsthand account of this nearly forgotten story which initially identified the young man as J. W. Weakley. Correspondence mentioned in the article then identifies the individual as C. F. Weakley. Additional information was later discovered in pension application records in the National Archives by well-respected Gettysburg historian/researcher/author William Frassanito that further identified this “citizen soldier” as Charles Francis Weakley. Weakley was actually 21 years old at the time, survived his wounds, and later enlisted in the 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment. Sadly, this other "citizen soldier" at Gettysburg died in November of 1864 reportedly while suffering an epileptic seizure, and never received the acclaim that he deserved and was accorded John Burns.

I was extremely fortunate to meet Mr. Frassanito in May of 2009, and he graciously showed me his files on Mr. Weakley. He also encouraged me to add that there was a 31-year-old civilian from nearby Petersburg (present day York Springs) by the name of Charles W. Griest who volunteered his services as a dispatch rider for Union troops and was severely injured when his horse was shot and fell on him on July 1.

To learn more about these forgotten heroes, I highly recommend Mr. Frassanito’s invaluable book "Early Photography at Gettysburg” (see my "Books Worth Reading" page).

Speaking of John BurnsThe statue of John Burns, located along the east side of Stone Avenue on McPherson's Ridge, is one of the many monuments and markers that have been moved in the past for one reason or another. In this case, Stone Avenue at one time ran on the other side of the Virginia worm fence behind the statue, then turned 90 degrees to the west and continued past the monument to the 7th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment. As a result, that monument now appears to be misaligned for the proper viewing of the front of it. Also, if you look on the other side of the fence behind the statue of John Burns, you can still see its former base nearby. So, when you see other monuments or markers as you drive on the battlefield that seem to be facing the wrong way, remember that is probably because the original park roads had been re-routed or removed entirely.

(Photo courtesy of the National Archives)

Other Gettysburg civilians who were woundedIn addition to John Burns, at least five other Gettysburg residents were also wounded even though they did not participate in the actual fighting like he did. According to the book “Gettysburg: The Last Invasion” by Allen Guelzo (published in 2013), they were Thomas D. Carson, Jacob W. Gilbert, Robert F. McIlhenny, Georgiana Little Stauffer, and Amos M. Whetstone.

Thomas D. Carson was a 27-year old bank cashier, Jacob W. Gilbert was a 25-year-old coach maker, and Robert F. McIlhenny was a 31-year-old merchant. Georgiana Little Stauffer was 24 years old at the time of the battle and lived on Baltimore Street. She was married to Jacob Stauffer, who was a member of Company K of the 1st Pennsylvania Reserves and was actually involved in the fighting at Gettysburg to defend Little Round Top on July 2, the same day Georgiana was shot in the hip while outside her home reportedly getting water to take to Union soldiers. Amos M. Whetstone was a 25-year-old Lutheran Theological Seminary student who was shot in the leg on July 4 while standing on a second floor porch at a boarding house on Chambersburg Street.

It should also be noted that according to “The Hospital on Seminary Ridge at the Battle of Gettysburg” by Michael Dreese (published in 2005), there was at least one more Gettysburg civilian like John Burns who fought alongside Union troops on July 1 and was also wounded. Frederick A. Lehman, a 16-year-old Pennsylvania College student who joined the fighting as it engulfed the college campus, was captured but released by the Confederates because of a personal appeal by a captured Union soldier, Lieutenant Charles Potts of the 151st Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment. Charles Potts later wrote an essay entitled “A First Defender In Rebel Prison Pens” and spoke of this college student who joined the fighting.

Like Amos Whetstone, Frederick Lehman suffered his wound on July 4 and also at a house on Chambersburg Street when he was shot in his right knee. The question remains: were there other civilian casualties ??? (A personal note: my sincere thanks to Codie Eash of the Seminary Ridge Museum and Education Center for his research assistance on this topic – thank you, Codie !!!)

The two "castles"

Every battlefield visitor to Little Round Top has no doubt observed the "castle" monument to the 12th New York and 44th New York Infantry Regiments:

There is also a monument honoring the Engineer Brigade (comprised of the 15th New York Volunteer Engineer Regiment and the 50th New York Volunteer Engineer Regiment) of the Army

of the Potomac which was designed in the shape of the "castle" insignia of the Union Army Corps of Engineers:

This unique monument, which is located along Pleasonton Avenue on Cemetery Ridge near the Pennsylvania Memorial, is probably overlooked by many people. That is truly a shame, especially since Major General Gouverneur K. Warren, Chief Engineer of the Union Army Corps of Engineers, is often referred to as "the Saviour of Little Round Top."

There are several interesting bronze plaques which can be found on this unusual monument. The two small circular plaques are large representations of the official Corps of Engineers uniform button that contains the lettering “ESSAYONS”, which is French for “Let us Try”.

The smaller plaque at the bottom of the monument (which appears on both sides of the monument) shows several items involved in building pontoon bridges as depicted in the large square plaque located further above on the western side of the monument:

The "Rule of 29" and the Pennsylvania Reserves

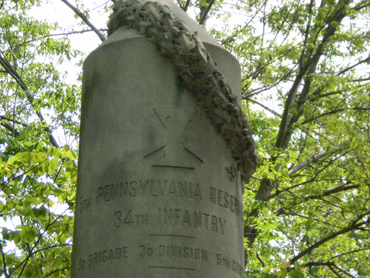

If you look closely at the many Union regimental monuments, you will see that some of them have dual military unit designations. Two such monuments are located at the summit of Big Round Top --- the monuments to the 5th Pennsylvania Reserves and to the 12th Pennsylvania Reserves:

The 5th Pennsylvania Reserves is also indicated as the 34th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, while the 12th Pennsylvania Reserves is also indicated as the 41st Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, and that leads us to what my friend and Licensed Battlefield Guide Mike Strong refers to as the "Rule of 29."

When President Lincoln called for troops after the attack on Fort Sumter in April of 1861, his quota of 14 regiments from Pennsylvania was quickly surpassed, and even though the quota was later raised because of the overwhelming number of volunteers, the remaining regiments were organized into the Pennsylvania Reserve Volunteer Corps consisting of 13 infantry, 1 cavalry regiment, and 1 artillery regiment. All of these regiments were not held in "reserve" very long --- 2 of the infantry regiments were mustered into the Union Army by late June, and all the remaining regiments were mustered in on July 22, 1861 after the First Battle of Bull Run to now complement the 29 infantry regiments from Pennsylvania already in service and were designated accordingly.

So, for example, when you hear or read about the 5th Pennsylvania Reserves and the fighting on July 2, and the speaker or the author then later refers to them as the 34th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment in the same context, just remember the "Rule of 29".

The first and the last monumentsThe first monument of any type was a marble urn placed in the Soldiers' National Cemetery in 1867 to honor the 1st Minnesota Infantry Regiment, which suffered approximately 82% casualties during its heroic charge led by Colonel William Colvill on July 2 against an entire Confederate brigade under the command of General Cadmus Wilcox:

The first monument placed on the battlefield (although the argument can obviously be made that the site of the cemetery was part of the battlefield) was to the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment in 1879 on Colgrove Avenue, which took part with the 27th Indiana Infantry Regiment in the ill-fated charge near Spangler's Spring on the morning of July 3 (see my "Off the Usual Path" page):

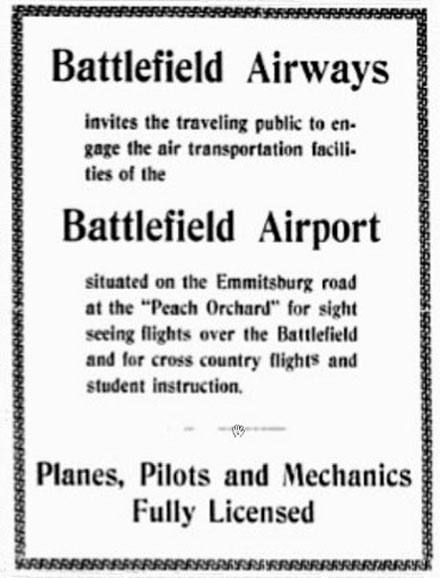

The last equestrian monument placed on the battlefield was in 1998 to honor Confederate General James Longstreet. Located in Pitzer's Woods just off West Confederate Avenue along Seminary Ridge, the monument is unusual for an equestrian one in that it is not set on a large pedestal:

The last Confederate monument, honoring the 11th Mississippi Infantry Regiment, was dedicated on the battlefield in 2000 on Seminary Ridge along West Confederate Avenue near McMillan's Woods (see the photo on the left) --- a marker was also dedicated just a few yards south of the Abraham Brian barn on Cemetery Ridge to indicate the position that regiment reached during Pickett's Charge (see the photo on the right):

The last Union monument, the Delaware State Monument, was also placed on the battlefield in 2000, and is located on the west side of the Taneytown Road at the entrance to the former location of the Visitor Center and Cyclorama building:

Look at the amazing detail, from the prostrate soldier’s chest wound to the bullet holes in the flag and the Union soldiers cheering along the stone wall:

In addition, there was a monument dedicated on the North Cavalry Battlefield on July 2, 2008,

at Hunterstown to honor the Union cavalry as well as General George Custer's participation in

the wild action that took place there 145 years ago on that day. The new granite monument can

be found at the "T" intersection of Hunterstown Road and Shrivers Corner Road roughly 4 miles north of Gettysburg (see my "Side-Trips" page).

It should also be noted that the Pvt. John Wesley Culp Memorial Camp #1961, Sons of Confederate Veterans of Gettysburg, erected and dedicated a small memorial in Gettysburg on July 6, 2013 to honor not only Confederate Private Wesley Culp and his brother in the Union Army, Lieutenant William Culp, but also as a reminder that the Civil War was indeed a war of “brother against brother.” This unique memorial is located near the entrance to the Gettysburg Heritage Center at 297 Steinwehr Avenue:

On July 5, 2015, a two-year-long Eagle Scout project by 15-year-old Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania Civil War drummer boy reenactor Andrew Adam culminated with the dedication of “Unity Park” at the intersection of Baltimore Street and Lefever Street in downtown Gettysburg.

Unity Park includes a monument of a drummer boy created by well known sculptor Gary Casteel (best known for his equestrian monument of General James Longstreet located on Seminary Ridge) to honor all the musicians of the Civil War. In keeping with the theme of “unity”, the monument was made of bronze from the North and the base of granite from the South, one walkway represents the North and the other the South that unite at the center, three flags (the current American flag, the Civil War American flag, and the flag of the Confederate government at the end of the war).

The first monument with a Confederate flagThe first monument that contained the depiction of a Confederate flag is actually on a Union monument which was dedicated in 1887. The medium sized monument is to the 1st New York Independent Battery, commanded by Captain Andrew Cowan, and honors their valiant efforts in the repulse of Pickett's Charge. Located just a few yards south of the famous "copse of trees" along Cemetery Ridge on Hancock Avenue, the bronze relief plaque on the north side of the monument depicts their heroic actions on July 3; if you look very closely in the far right corner, you will see a Confederate flag waving in all its glory:

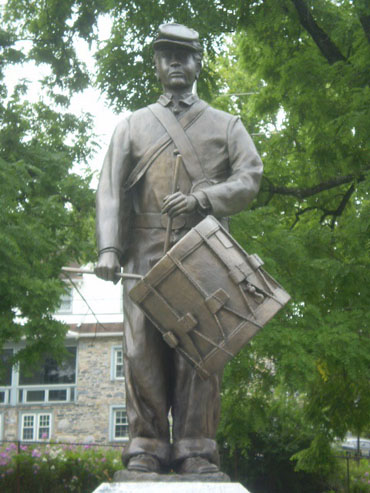

The 4th of July markerWhile it is not really a monument commemorating Independence Day, the small marker located along the west side of the Emmitsburg Road roughly 100 yards south of the Nicholas Codori barn indicates the location of the skirmish line of the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry Regiment on July 4, 1863:

It is the only marker that I am currently aware of that only indicates a unit's position the day after the battle (the regiment did suffer casualties from rifle and artillery fire on July 4), but I am still checking into this. If anyone is aware of any others, please let me know and I will add them to this section.

The monument bases that aren'tAt first glance, what the small stone base near the summit of Big Round Top would at first appear to be is the remnants of a base to a monument that had been moved. That would be seem to be a very reasonable assumption since there were observation towers (an early wooden one, and then a 60-foot tall metal one that was removed in the 1960's) on Big Round Top. However, when I saw this stone base for the first time, I asked several Park Rangers and two Licensed Battlefield Guides over the last few weeks in person or via emails if I was correct. Well, to make a long story short, the small stone base is the remnants of one of the four bases for the metal tower (which I remember going up in once when I was about 12 years old):

(Photo courtesy of the Center for Civil War Photography http://www.civilwarphotography.org)It should be noted that two other observation towers were also removed in the past -- the wooden tower on East Cemetery Hill was removed in the 1890’s to make room for the equestrian monument to Union General Winfield S. Hancock, and the metal tower in Ziegler’s Grove on Cemetery Ridge was removed in the 1960’s to make room for the former Gettysburg Cyclorama/Visitor Center, which itself was removed in the early part of 2013 by the Gettysburg National Military Park:

(Photo courtesy of Mike Waricher and the GNMP)

(Photo courtesy of Mike Waricher and the GNMP)Speaking of observation towers, the wooden 60-foot-tall observation tower on East Cemetery Hill was built in 1878 in the exact location where the equestrian monument of General Winfield Hancock would later occupy. The admittance fees were $0.25 for adults and $0.15 for children, and there was also a gift shop located in the bottom. The sign reads “Don't Miss a View of the Great Battlefield From the Top of the Observatory-It is Grand Beyond Imagination". The tower was taken down in 1895; the equestrian monument was dedicated in 1896.

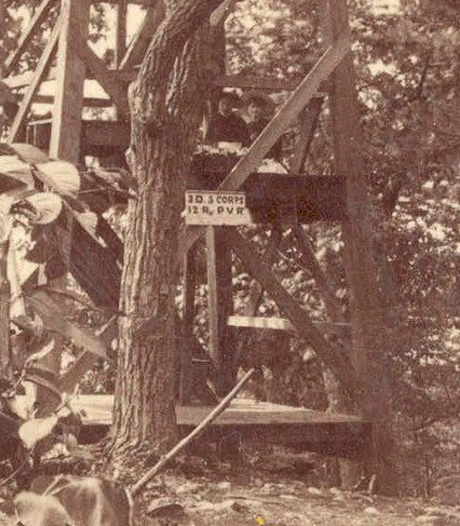

(Photo courtesy of Greg Ainsworth and the GNMP)Here are photos of the wooden tower that was once located on Big Round Top (the sign reads “3D V CORPS 12 R P.V.R.” denoting the 12th Pennsylvania Volunteer Reserves Infantry Regiment of the Third Division of the Union V Corps):

(William H. Tipton photo courtesy of the GNMP)

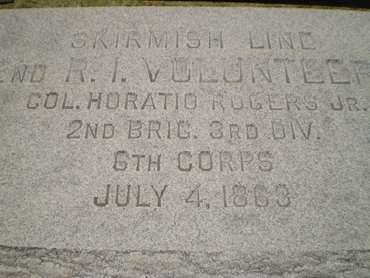

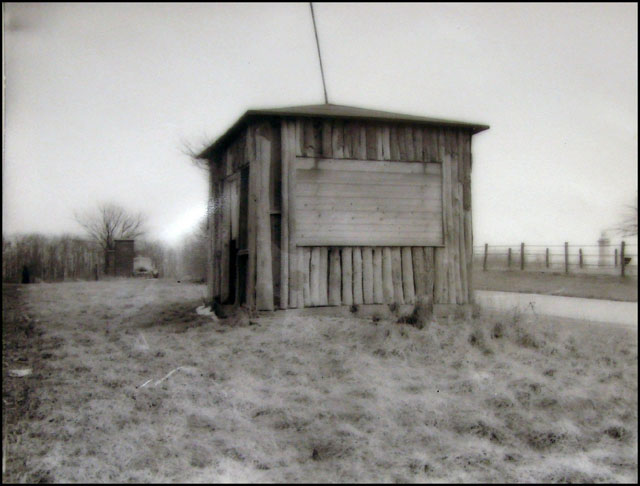

Yet another example is the larger slab measuring roughly 12 feet by 12 feet that can be found north of the famous "railroad cut" where Reynolds Avenue intersects at the "T" of Wadsworth Avenue and Buford Avenue. This large slab was actually the foundation of an office/ticket booth for an airport that once existed in the area between the intersection and Oak Hill during the 1920's and 1930's:

(Photo courtesy of the GNMP and Mike Waricher)What is perhaps even more astounding to me is that there was not just one airport on the existing battlefield over the years, but two --- the other grass strip airport was located on the southern part of the battlefield below the Millerstown Road and between Seminary Ridge and the Emmitsburg Road !!! Can you imagine that being permitted today ???

(Images courtesy of http://www.airfields-freeman.com)

The marker base that isn'tWhile on a Battle Walk in September of 2011 about the Florida Brigade (see “The Florida Brigade” on my “Battle Walks” page), I noticed a small rectangular stone slab a short distance from a tree on the western side of the Emmitsburg Road at the former site of the Peter Rogers farm. Measuring roughly 22” by 40”, I thought that the small stone slab originally was the base for a smaller sized “advanced position” or “skirmish line” marker. After contacting several experts, including National Park Ranger/Historian John Heiser, it would appear that the small stone slab is still a mystery. One theory is that it was a discarded stone (either chipped or cracked) from one of the nearby monuments and that perhaps Mr. Rogers or one of the later owners of the property got the stone and placed it there as a step to the front porch of the house. That being said, the close proximity to the tree and its sharp angle from the road makes me wonder about that theory. Another theory is that it was the base for the 1st Massachusetts Infantry Regiment skirmish line marker before it was moved later to its current position roughly 300 yards further west (see the “Skirmish lines and smaller units” section on my “Off The Usual Path” page). However, there is no actual documented evidence that the marker was ever moved, and to my knowledge there is no Civil War era photograph of the Peter Rogers house that might shed light on this mystery. So, what is it ???

The monument base with handprints

Most monument bases on the battlefield are made of stone, but there is one monument on Big Round Top, the monument to the 12th Pennsylvania Reserves/41st Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment (see the “The Rule of 29” section on this page) that has a base covered in concrete. That is somewhat unusual in itself, but what is more unusual is that if you look at the northwest corner of the base, you can see three or perhaps four small handprints. For all of us old-timers, we can recall placing coins or our own handprints (with our parents’ permission, of course) in our new sidewalk or porch, so perhaps this is a similar case as well.

It is my understanding that the base of the monument was probably repaired in the 1960’s when the observation tower was removed from the summit of Big Round Top. But the question remains: whose handprints are they ???

The monument that never was

While most visitors to the battlefield have at least heard of the monument to the 20th Maine Infantry Regiment that is located on the southern spur of Little Round Top, I would venture it would be a safe bet that very few people realize that a Confederate monument to the 15th Alabama Infantry Regiment was actually proposed for Little Round Top, and which would have been placed behind the lines of Colonel Joshua L. Chamberlain's men.

Years after the battle, Colonel William C. Oates attempted to obtain official approval for placing a monument to his regiment, the 15th Alabama Infantry Regiment, on a boulder that is roughly 60 yards behind the center (and about 15 yards behind the left flank and 40 yards behind the right flank) of the position of the 20th Maine Infantry Regiment on July 2. That boulder is reported to be the approximate location where Colonel Oates' brother, Lieutenant John A. Oates, fell mortally wounded during one of the attacks that did temporarily break through the Union lines:Colonel Joshua L. Chamberlain constantly opposed all efforts to have any monument placed behind his lines, denying that his regiment was driven back so far that day. Colonel Oates also wanted the monument in order to honor his brother, but even this noble goal apparently elicited very little or no sympathy from his Union counterpart, even though Colonel Chamberlain also had a brother who was involved in the fighting, but who fortunately survived.

(The 20th Maine's left flank marker is visible on the left, and the monument to the 20th Maine is on the right)

The monument was never approved, but the proposed inscription still survives. To read more about the inscription and the interesting story behind "the monument that never was," go to the website at http://www.users.globalnet.co.uk/~pardos/JohnOates.html.

Another monument that never wasAnother monument that was proposed but never erected was to be for Union General Elon Farnsworth, the 23-year old cavalry officer (see the “The South Cavalry Battlefield --- the other cavalry action on July 3” section on my “Off the Usual Path” page) who died while leading an ill-fated cavalry charge against the right flank of the Confederate Army after Pickett’s Charge had been repulsed. In the October 4, 1888 edition of the newspaper The National Tribune, it was reported that:

“A monument to Gen. Elon J. Farnsworth, who commanded the brigade and fell leading what at the time was considered a desperate and hopeless charge, is proposed to be erected. It is to be placed on the spur of Round Top, southeast of Slyder’s house where he fell. It is to be composed of a mound of boulders gathered in the neighborhood, upon which is to be placed a pentagonal granite shaft, on each of the faces of which is to be inscribed historical data relating to the regiments of the brigade and battery engaged. The mound and shaft are to be surmounted by a statue of Farnsworth. It is desired that all surviving members of this brigade actively interest themselves in this project, in order that it may be made one of the most striking features of the field, as his (Farnsworth’s) fall is one of the most romantic incidents of the battle of Gettysburg. Having won in the 8th Ill. Cav. His promotion, which occurred four days before he was killed, members of that regiment are deeply interested in these proceedings.”

Unfortunately, the reason or reasons why this monument was never erected are forever lost to history.

(Photo courtesy of USAMHI)

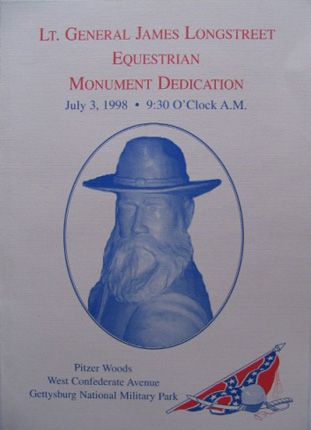

A monument that almost wasThe equestrian monument (by sculptor Gary Casteel and dedicated on July 3, 1998) to Confederate General James Longstreet is located on the west side of West Confederate Avenue in Pitzer’s Woods, but it is neither the original location, design, or sculptor !!!

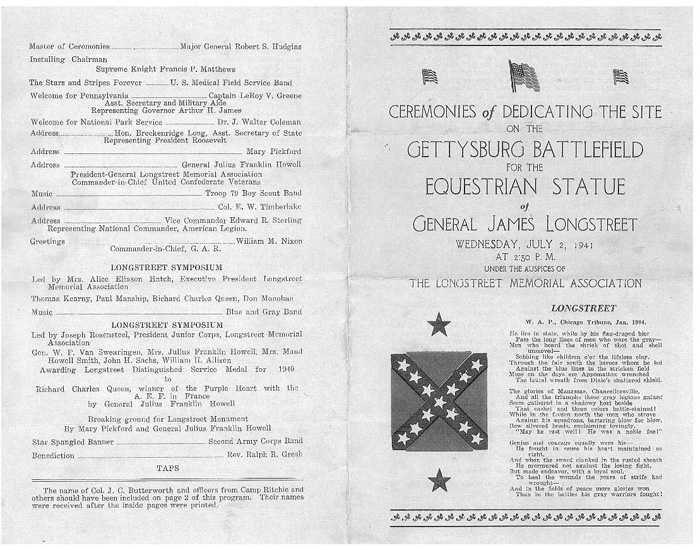

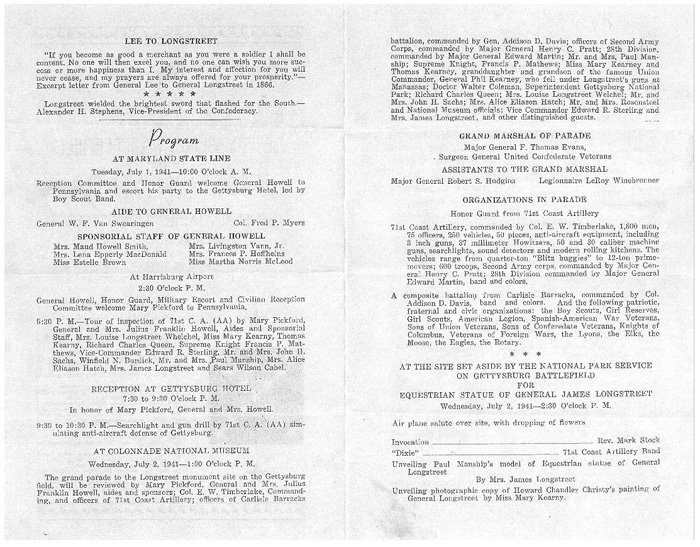

Led by primarily by Helen Dortch Longstreet (General Longstreet’s second wife and widow) and Julius Franklin Howell (commander of the United Confederate Veterans), the Longstreet Memorial Association was created in 1938 to honor General Longstreet and erect a statue in his memory on the Gettysburg battlefield. After many years of hard work, approval by the National Park Service was granted and a fundraising campaign was about to begin after a groundbreaking ceremony on July 2, 1941 at the proposed site on the west side of South Confederate Avenue about .4 miles from the intersection of the Emmitsburg Road:

(L to R: GNMP Superintendent J. Walter Coleman, Helen Dortch Longstreet,

actress Mary Pickford, and UCV Commander Julius F. Howell)

(Photo courtesy of the GNMP)

(Images courtesy of Dan Paterson and The Longstreet Society)

Sculptor Paul Manship had been commissioned to design the proposed monument (12 feet tall and 12 feet wide and surrounded by stone seats for viewing), with a model of the final version shown below:

(Photo courtesy of Licensed Battlefield Guide Tim Fulmer and the GNMP)However, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 and the entry of the United States into World War II, all fundraising efforts for the monument were understandably put on hold. The majority of the funds that had been collected thus far toward the estimated cost of $100,000 was donated to the war effort and left enough to pay for the current monument on General Longstreet’s grave in Gainesville, Georgia:

(Photo courtesy of Dan Paterson and The Longstreet Society)In spite of all efforts to revive interest after World War II, the monument was never funded nor built. Helen Longstreet died on May 3, 1962. Roughly three years later on August 25, 1965, the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors monument was dedicated on the original ground selected for the monument to General Longstreet:

The "recycled" monumentMany regiments have more than one monument on the battlefield, with one reason being that

the survivors often had newer and more elaborate monuments constructed years later to replace

the original ones. More often than not, the original monument was then moved and placed at another location where the regiment also saw action. In one instance, the survivors of the 2nd New York Cavalry Regiment were so dissatisfied with the design of their original monument before it was even placed on the battlefield that it was sold for $50.00 and then "recycled" as a monument for the local G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic) post located at 53 East Middle Street (about one block southeast of the square):

A final version of the monument was eventually agreed upon, and can be found in the vicinity of the Pennsylvania Monument on Cemetery Ridge roughly 50 yards north of the "T" intersection of Humphreys Avenue and Pleasonton Avenue (the monument is on the far left in the picture on the left below):

As you can see, the two monuments are still very similar, so I wonder what was so objectionable and what was changed --- the inscription ???

The "rejected" monumentThere was one monument that was actually “rejected” by survivors of a Union infantry regiment after it had already been placed on the battlefield. The original monument to the 149th New York Infantry Regiment (see the “Faces of the Battle” section on my “Something Different” page) at its dedication ceremony in 1889 created such an uproar that the veterans refused to accept it and asked the New York Monuments Commission to have it replaced with a different monument, which finally occurred in 1892:

(Photo courtesy of the GNMP and Mike Waricher)

The "recycled" monument capstoneLocated on the east side of Sedgwick Avenue along Cemetery Ridge halfway between Wheatfield Road and United States Avenue, there is a stone marker about 6 feet tall that, in addition to the typical upright cannon tube along the road, also indicates the location of General George Sykes’ Union V Corps headquarters. What is interesting about this marker is that from what I have read, it was actually planned to be used as the capstone for the “castle” monument to the 12th New York and 44th New York Infantry Regiments located on the summit of Little Round Top (see the “The two “castles” section above on this page):

Modified monumentsOther interesting monuments are those that were modified at one point or another in time, such as the ones shown below:

23rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment

(see the “Faces of the Battle” section on my “Something Different” page)

(Photo courtesy of the GNMP and Steve Floyd)

28th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment

(located on the west side of Slocum Avenue as you ascend Culp’s Hill)

(Photo courtesy of the GNMP and Mike Waricher)

63rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment

(located along the west side of the Emmitsburg Road across from the Peach Orchard)

(Photo courtesy of the GNMP and Steve Floyd)

155th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment

(see the “Faces of the Battle” section on my “Something Different” page)

(Photo courtesy of the GNMP and Mike Waricher)

8th Ohio Infantry Regiment

(located along the west side of the Emmitsburg Road just south of downtown Gettysburg)

(Image courtesy of the Ohio Historical Society)

Monuments with more than one Union Corps insignias

Most, if not all, of the Union monuments on the battlefield contain a depiction of some type and size of their respective Corps insignia established in early 1863 by Major General Joseph Hooker:

Headquarters Army of the Potomac

March 21, 1863

For the purpose of ready recognition of corps and divisions in this army, and to prevent injustice by reports of straggling and misconduct through mistake as to organization, the chief quartermaster will furnish without delay the following badges, to be worn by officers and enlisted men of all regiments of the various corps mentioned. They will be securely fastened upon the center of the top of the cap.

Inspecting officers will at all inspections see that these badges are worn as designated:

First Corps, a sphere - First Division, red; Second, white: Third, blue.

Second Corps, trefoil - First Division, red; Second, white: Third, blue.

Third Corps, lozenge - First Division, red; Second, white: Third, blue.

Fifth Corps, Maltese cross - First Division, red; Second, white: Third, blue.

Sixth Corps, cross - First Division, red; Second, white: Third, blue. (Light Division, green.)

Eleventh Corps, crescent - First Division, red; Second, white: Third, blue.

Twelfth Corps, star - First Division, red; Second, white: Third, blue.The size and colors will be according to pattern.

By command of Major-General Hooker: S. Williams, Assistant Adjutant-General

However, the monument to the 90th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment located at the northern end of Ziegler's Grove on Cemetery Hill has two insignias, those of the I Corps and the V Corps.

At the beginning of 1864, the Union I Corps was consolidated with the V Corps, with the 90th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment moving from its former brigade to join the 13th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, the 39th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, the 16th Maine Infantry Regiment, and the 104th New York Infantry Regiment to constitute the new First Brigade of the Second Division of the V Corps.

The 39th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment was not at Gettysburg, but the other regiments were. However, of all the former I Corps regiments that also later served in the V Corps, this monument to the 90th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment is the only one with the double Corps designation:

For information and photographs of the other monument to the 90th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment which is unique in its own right, see the “Unusual monuments” section and “Other monuments with animals” section on my “Something Different" page.

Located on the west side of the Taneytown Road roughly 15 yards north of General George Meade’s headquarters at the Lydia Leister house is the monument to the 93rd New York Infantry Regiment. After the Union III Corps was broken up in May of 1864, the 93rd New York Infantry Regiment was reassigned to the II Corps and chose to note that fact near the top of the north side of the monument with a trefoil and a diamond placed directly on the trefoil. The monument also has a diamond near the base of the south side of the monument:

Located in the southern end of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery is the monument to the 1st Battery, New Hampshire Light Artillery. What is extremely interesting to note is that the Battery was assigned to the Artillery Reserve during the Battle of Gettysburg, and yet there are three Union Corps symbols on the monument (the circle, the trefoil, and the diamond). During the Civil War, the 1st Battery, New Hampshire Light Artillery had actually served at one point in three Union Corps in addition to the Artillery Reserve -- the I Corps, the II Corps, and the III Corps:

The "unofficial" memorial marker

If you visit the Battlefield Military Museum located along the Baltimore Pike just south of East Cemetery Hill, look inside a small enclosed area in the parking lot and you should be able to find a small 12" by 24" memorial stone:

As told to me by George Marinos, the museum's longtime owner, a contingent of 18th Mississippi Infantry Regiment reenactors attempted to place the memorial stone (complete with the hole to hold a flag) in the Wheatfield about 20 years ago. They were soon stopped by a Park Ranger and ordered to remove it since it had not been officially authorized to be placed on the battlefield. To make a long story short, eventually Mr. Marinos offered to take it and place it on his property, and this small "unofficial" memorial marker to the 18th Mississippi Infantry Regiment has remained there ever since.

Marker RowWhat I refer to as "Marker Row" is technically a row of interpretive tablets, and there are actually two rows, one Confederate and one Union. The Confederate "row" is located along Seminary Ridge on the west side of West Confederate Avenue across from the National Guard Armory, with 10 chronological tablets detailing the Confederate Army's movements from June 26 - July 4, 1863:

The Union "row" is located on East Cemetery Hill on the east side of the Baltimore Pike across from the entrance to the Evergreen Cemetery, with 9 chronological tablets detailing the Union Army's movements from June 29 - July 7, 1863. Unlike the Confederate tablets which face the road, the Union tablets face away from the road (presumably to prevent traffic accidents on this much more heavily traveled downtown venue):

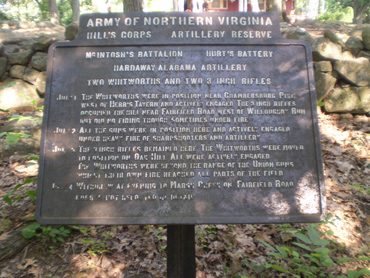

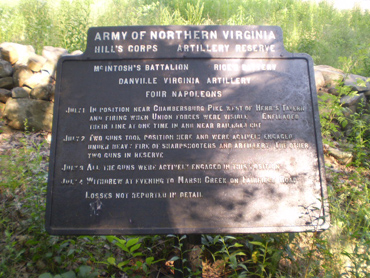

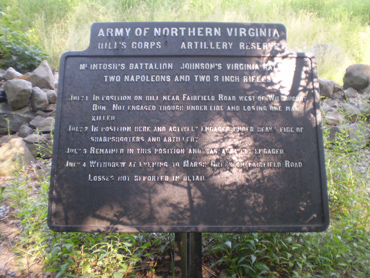

Just north of the Confederate “Marker Row” is a small set of markers that is often overlooked because attention is focused on the east side of the road as you approach the fields over which Pickett’s Charge took place. Starting roughly 100 yards south of the intersection of Route 116 (the Fairfield Road) and West Confederate Avenue are the Confederate artillery unit markers to the four batteries of Major David G. McIntosh’s Battalion, part of the Artillery Reserve of General A. P. Hill’s III Corps, marking the positions they held on July 2 and 3. Shown below are the markers (from north to south on Seminary Ridge) for Lieutenant Samuel Wallace’s Second Rockbridge Battery, Captain William B. Hurt’s Hardaway Battery, Captain Robert S. Rice’s Danville Battery, and Captain Marmaduke Johnson’s Virginia Battery, most of which are roughly 50 yards apart -- the southernmost marker for Captain Johnson’s Battery is roughly 65 yards south of the other three markers and is partially concealed by the treeline:

Captain William B. Hurt’s Battery was the Confederate artillery battery which had the British Whitworth breechloading cannons which can be seen on Oak Hill (see the “Cannons, Cora, and Penelope” section at the beginning of this page).

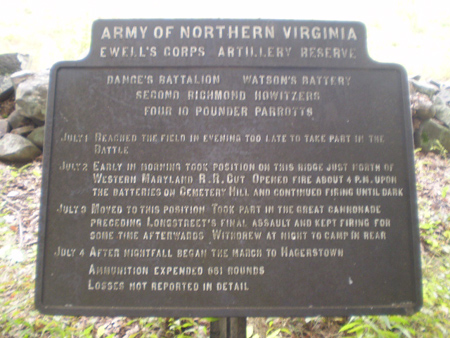

In addition, located roughly 50 yards south of the marker for Captain Marmaduke Johnson's Battery mentioned above is one of two markers for Captain David Watson's Battery of Captain Willis J. Dance's Artillery Battalion:

The other marker for Captain David Watson's Battery is located directly across the road on the east side of West Confederate Avenue about halfway between the present-day National Guard Armory and the David McMillan house:

Small non-military markersThere are a few small flank marker sized stones that can be found but do not have any military significance or not the typical military significance associated with stone markers that size. One of these markers can be found at 242 Baltimore Street outside the home of Jennie Wade's birthplace:

At first glance, it looks like it perhaps may be a marker for one of the Confederate infantry regiments that manned barricades there throughout the battle. In reality, it is a "mile-marker" indicating the distance to Baltimore, another subtle reminder as to how vital this small town was in regard to commerce with all its intersecting roads:

There is also a small stone about 5 yards south of the monument to the 126th New York Infantry Regiment that is located in Ziegler's Grove on Cemetery Ridge about 100 yards north of the Abraham Brian house along Hancock Avenue:

The small stone is, for lack of a better name, the "Cope meridian marker" used by Chief Engineer Lieutenant Colonel E. B. Cope in 1893 to establish a meridian line for surveying the battlefield to determine the exact position of every military unit at Gettysburg in order for him to compile accurate post-war maps:

When you are exploring parts of the battlefield that are on the edge of the Park's boundary line, if you look close enough, you may see some of the relatively small stone boundary markers like the ones pictured below in the area around Culp's Hill:

As you can see, they are not the same --- the size and shape varies depending upon when they were installed. Here is an easier one to spot that is located just inside the wooden fence at the intersection of Slocum Avenue and Wainwright Avenue:

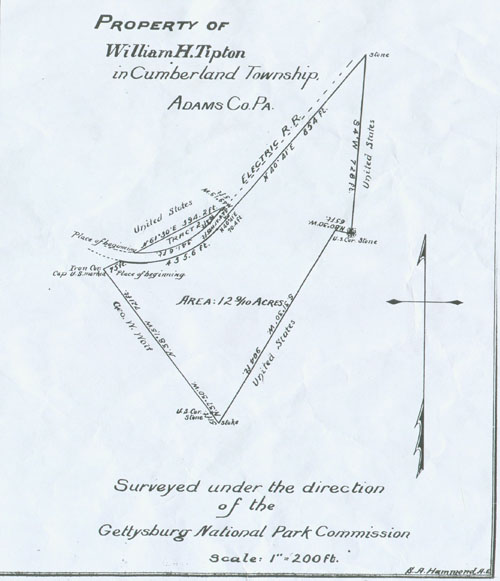

As mentioned on my “Off the Usual Path” page, at one point in time there were three amusement parks on the southern portion of the battlefield: Round Top Park, Wheatfield Park (also known as Wible’s Grove), and Tipton Park. Tipton Park was owned by local photographer William H. Tipton and was roughly 13 acres in size located east of Devil’s Den. In addition to two small National Park Service markers, there are three small stone markers with a “T” carved on the top of them. Two of them are located roughly 30 yards apart about 70 yards northeast of the monument to the 40th New York Infantry Regiment (see the “Rock carvings and inscriptions” section on my “Something Different” page) but are difficult to find (and one of them is lying on its side) in the tall summer grass; the third one is also difficult to find depending upon the time of year and is located just about 20 yards east of the bend in the old trolley path where it crosses Plum Run just east of the southern end of Devil’s Den and only 5 yards north of the path behind the small boulder with an iron pin on top of it. Here are photos of the two “T” markers north of the monument to the 40th New York Infantry Regiment:

Here is a photo of the “T” marker roughly 10 yards north of Plum Run about 20 yards east past the bend in the old trolley path southeast of Devil’s Den behind the small boulder with an iron pin on top of it:

(Map courtesy of Lew and Ginny Gage and the GNMP)

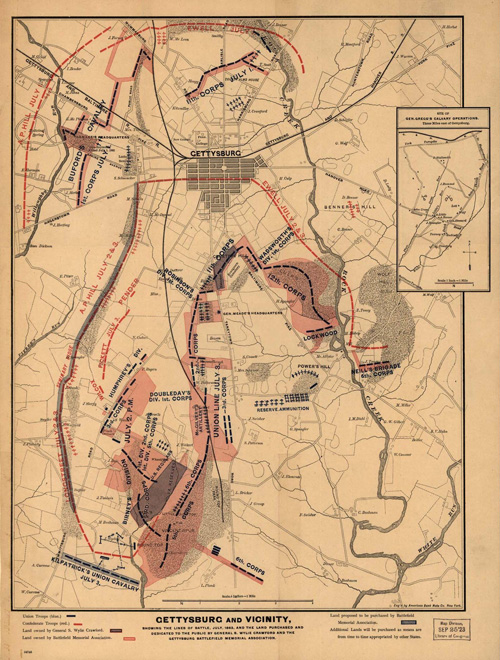

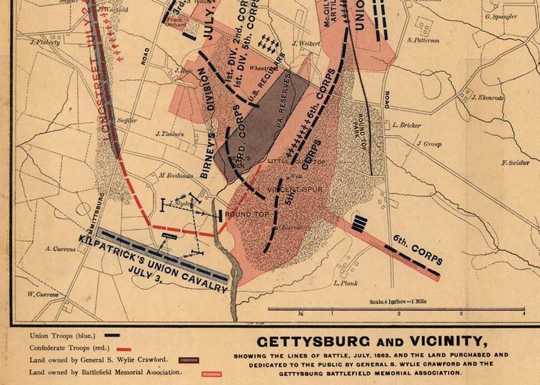

Crawford ParkUnion General Samuel W. Crawford, who commanded the Third Division (two infantry brigades of nine regiments of Pennsylvania Reserves) of General George Sykes’ V Corps at Gettysburg, often visited the battlefield after the Civil War. Crawford became concerned with physical changes being made to the battlefield (especially stone quarrying and tree cutting), and in 1872 purchased 47 acres of land in the valley of Plum Run and Devil’s Den west of Little Round Top where his Third Division fought on July 2, 1863 for $500.00. The rectangular tract was known as Crawford Park or Crawford’s Glen:

(Map courtesy of the GNMP)

Samuel Crawford later became a member of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA) and had disputes with the other members regarding how Crawford Park was used. Crawford refused to allow monuments to be placed on his 47 acres but also unsuccessfully promoted his plan to build a 120-foot-long memorial hall on the summit of Little Round Top that would contain a chapel, memorabilia, and monuments to those nine infantry regiments under his command.

Even though General Crawford had initially intended that Crawford Park/Glen would be given to the GBMA after his death, the many disagreements and arguments he had with his fellow members must have seeded so much resentment that at the time of his death in 1892, no official arrangements had been made for such a land transfer. In addition, it should be noted that Crawford had granted a right-of-way for the Gettysburg Electric Railway (the battlefield trolley line vehemently opposed by the GBMA) through the valley of Plum Run Valley over his property for one dollar, another good indication of his dissatisfaction with the GBMA and his possible “payback” for not getting approval for his proposed 120-foot-long memorial building on the summit of Little Round Top.

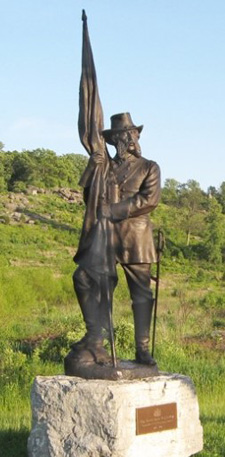

The GBMA did not acquire the land on which the present-day Crawford Avenue exists until May of 1893 after negotiations with General Crawford’s heirs. In 1988, a monument to General Crawford was dedicated in what was Crawford Park/Glen on the east side of Crawford Avenue about 100 yards south of Wheatfield Road:

It is somewhat ironic that General Crawford's statue stands on ground where he opposed placement of monuments, wouldn’t you agree?

Time and temperature

I have found one source that delves into the actual weather conditions during the battle, the small handy reference book "Gettysburg: By the Numbers" (see my "Books Worth Reading" page). To me, it was interesting to learn that according to those records, July 3, 1863, was the only day of the 3-day battle where the daylight temperature actually approached the 90-degree mark (87 degrees during the time of Pickett's Charge).

Perhaps the most important factor to remember is that Daylight Saving Time did not yet exist. As a result, this should be taken into account when reading about the evening and early morning attacks on Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill, and perhaps as a possible factor to consider as to one of the reasons why General Meade did not ultimately mount a counterattack after Pickett's Charge was repulsed.

The first book written about the Battle of Gettysburg

The daily battlefield weather data mentioned in the section above was recorded by Professor Michael Jacobs, who lived at the northwest corner of Washington Street and Middle Street in downtown Gettysburg and taught Mathematics, Chemistry, and Natural Philosophy at Pennsylvania College (later named Gettysburg College). Professor Jacobs later wrote the book “Notes on the Rebel Invasion of Maryland and Pennsylvania and the Battle of Gettysburg”, which is considered to be the first book ever written about the Battle of Gettysburg:

Michael Jacobs

The first book about the Battle of Gettysburg

Geology of the battlefieldThere is a report from 2006 containing more than 100 pages available from the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources which addresses the geology of Adams County and how it affected the battle. The report contains many photographs and maps, and can be found at http://maps.dcnr.pa.gov/publications/Default.aspx?id=595.

Another resource from the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources can be found at http://www.docs.dcnr.pa.gov/cs/groups/public/documents/document/dcnr_014596.pdf.

It is interesting to learn about this aspect of the battle and how the terrain and geology did more than make it difficult for the dead to be buried (more often than not) in shallow graves. I urge all students of the battle to take time to look into this seemingly boring report, if only for the photographs and maps--- I think they will be glad they did.

"Witness trees"While it is no doubt that there are many trees still standing that were "witnesses" to the battle (not counting, of course, some of the famous "copse of trees" on Cemetery Ridge) I have read of only a dozen or so that have some documentation. These include the two sycamore trees on Baltimore Street, a honey locust tree in the Soldiers' National Cemetery, a black walnut tree near the "copse of trees," and a white oak tree on the Abraham Trostle farm near the area of Union General Daniel E. Sickles' headquarters on July 2 and about 40 yards south of the monument marking the spot where he was hit by cannon fire and lost part of his right leg:

There is a white oak tree that is easy to find which is located on the crest of Devil's Den where Captain James E. Smith's 4th New York Battery was positioned on July 2:

There is a white oak tree on Culp's Hill that is fairly easy to find: it is about 30 yards behind and along a narrow footpath to the right of the monument to the 78th and 102nd New York Infantry Regiments on the east side of Slocum Avenue:

The honey locust tree, located roughly 50 yards from the monument to President Abraham Lincoln and the Gettysburg Address, was damaged during a storm on August 7, 2008:

The "Heth wounding tree," so named because it reportedly marks the approximate location where Confederate General Henry Heth of General A. P. Hill's III Corps was wounded in the head on July 1, was struck by lightning about 10 years ago and so severely damaged that it was cut down. It is still interesting, at least for me, to sit on that stump and recall how General Heth had always said that what saved him that day was the extra wadding he had to put in the oversized hat which he "requisitioned" earlier in Pennsylvania. To find the tree stump, park on Stone Avenue along McPherson's Ridge near the statue of "citizen soldier" John Burns. Walk south along the east side of Stone Avenue about 40 yards and then walk east roughly another 40 yards along a Virginia worm fence across the road from the monument to the 7th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment (the monument is visible in the background below):

The "Gibbon wounding tree," however, is still intact, and marks the approximate location where General John Gibbon, commander of the Second Division of General Winfield S. Hancock's Union II Corps, was wounded on July 3 during Pickett's Charge shortly after he took over command of the II Corps when General Hancock was wounded. The black walnut tree is located approximately 150 yards south of the famous "copse of trees" on Cemetery Ridge along the west side of Hancock Avenue and across from the monument to Battery C of the 5th U.S. Artillery (commanded by Lieutenant Gulian V. Weir):

Yet another “wounding” tree is along the east side of West Confederate Avenue on Seminary Ridge roughly 30 yards south of McMillan’s Woods and is the first tree on the south side of the tablet for Major William J. Pegram’s Artillery Battalion. Located along the stone wall, this oak tree reportedly marks the approximate location where Confederate General William D. “Dorsey” Pender, while commanding his division of General A. P. Hill’s III Corps on the afternoon of July 2, was mortally wounded by artillery fire:

There are two sycamore “witness” trees along the east side the 400-block of Baltimore Street roughly 70 yards from each other (there had been three until a few years ago, but one suffered some damage and had to be replaced by a new sycamore tree seen in the middle of the photo on the left below). One is directly across the street from the Farnsworth House Inn, and the other one to the south has a small ground-level plaque indicating that “President Lincoln passed by this tree on November 19, 1863.” But he passed by the other tree too …

I am sad to report that the two linden “witness” trees over 170 years old that were located in front of the Christ Lutheran Church at 44 Chambersburg Street were cut down in January of 2010 because they were reportedly dying. Here is a photograph I took in June of 2009:

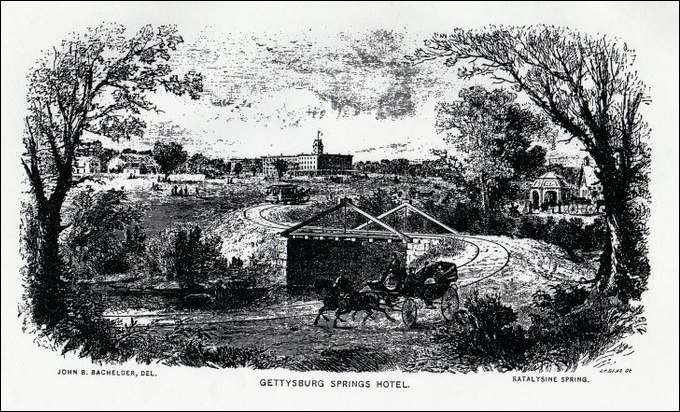

The Springs HotelIn 2006, while "Googling" for battlefield maps of Gettysburg, I came across a 1904 map indicating the positions of monuments. What caught my attention, however, was that there was a "Springs Hotel" marked on the west bank of Willoughby Run in the area where General John Archer's Brigade crossed and then encountered the Iron Brigade on July 1. I had never heard of this hotel, and did some research as well as discussing it with Park Ranger Troy Harman after one of his enjoyable and enlightening "Battle Walks."

I mentioned to Troy that I had found the Springs Hotel marked on a map and then later read

an article (http://www.emmitsburg.net/archive_list/articles/history/gb/property/springs_hotel.htm)

I had found on the Emmitsburg Area Historical Society's website, and he mentioned that that was how Springs Avenue got its name --- a horse-drawn trolley line ran along present-day Springs Avenue and linked the railroad station downtown with the hotel. That small fact was of particular interest to me, since my great-great grandfather, who had been wounded in the fighting for the Wheatfield, returned after the war and built his own house on Springs Avenue, which I am proud to say, still stands today.

But back to the story of the "Gettysburg Springs Hotel," or "Springs Hotel" as it was also referred to. Mineral springs were found on the farmland as early as the 1830's, and a health resort/spa was built in 1869 by the Gettysburg Katalysine Springs Company. However, the spa eventually closed in the 1890's, and the four-story hotel, which housed guests for the 50th anniversary of the battle in 1913, was unfortunately destroyed only a few years later by fire in 1917.

(Photo courtesy of the National Archives)

(John Bachelder sketch courtesy of Mike Waricher)

(remnants of the bridge abutment on

the east side of Willoughby Run)(remnants of the bridge abutment on

the west side of Willoughby Run)

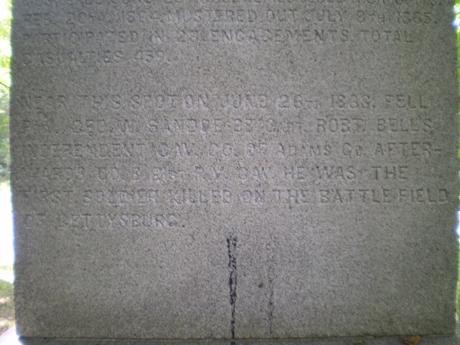

The first Union soldier killed at GettysburgThe first Union soldier killed in action at Gettysburg was shot by Confederate troops not on July 1, 1863, but on June 26, and he was actually born in the Gettysburg area. George Washington Sandoe was a 20-year old private in Bell's Independent Cavalry, Company B, a company of approximately 90 volunteers from Adams County commanded by Captain Robert Bell. Mustered in only three days before on June 23, Sandoe and another local soldier, William Lightner, were on a scouting patrol just south of Gettysburg near the Baltimore Pike when they encountered Confederate cavalry pickets of Colonel Elijah V. White's 35th Battalion Virginia Cavalry. Despite being ordered to halt by the pickets, Lightner jumped his horse over a fence and escaped down the Baltimore Pike, but Private Sandoe was not as fortunate. Before he tried to follow suit, Sandoe stopped and fired a shot at the Confederate pickets, and then attempted to outrun his pursuers. Unfortunately, a Confederate bullet found its mark before he could do so, and thus, George Washington Sandoe became the first Union soldier killed in action at Gettysburg:

(Image courtesy of Debra Sandoe McCauslin)After heading east to Hanover and then York, and helping to defend the Wrightsville Bridge until it was burned on June 28, the company retreated to Harrisburg and was merged as Company B with the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment, which was later ordered to Gettysburg after the battle to guard prisoners and perform other duties. There are two monuments to the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment approximately 30 yards apart on the east side of the Baltimore Pike about .9 of a mile south of the entrance to the new Museum and Visitor Center, and both also honor the brave 20-year-old Gettysburg native for his valiant service that day in June:

(the monument to the north)

(close-up of the inscription on the front of the monument)

(the monument 30 yards to the south)

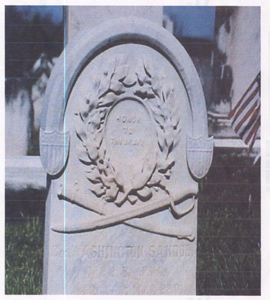

(close-up of the inscription on the back of the monument)George Washington Sandoe was later laid to rest in the cemetery at Mount Joy Lutheran Church, which is located about 5 miles south of Gettysburg on the west side of the Taneytown Road:

His original tombstone still exists (see the photo below on the left), but it was replaced by the one

that you can now see just inside the portion of the cemetery fence that runs along the road (see the photo below on the right):

The first Union soldier killed in Pennsylvania during the Gettysburg CampaignThe main Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania began on the morning of June 22, when General Richard S. Ewell's II Corps left their camps in Maryland and headed north across the Mason-Dixon Line. General Albert G. Jenkins' cavalry brigade was the advance force that first crossed the border into Pennsylvania, screening the infantry of General Robert Rodes’ Division. Passing through Greencastle, located about four miles north of the border, members of the 14th Virginia Cavalry Regiment encountered Captain William H. Boyd's onrushing Company C of the 1st New York Cavalry Regiment (which had recently been sent by train from Harrisburg to Chambersburg) near the William Fleming farm. In a brief exchange of gunfire, one Union cavalryman, Sergeant Milton Cafferty, was wounded in the leg and Corporal William H. Rihl was shot in the head and killed.

Not all of the members of the 1st New York Cavalry Regiment were from that state – Company K was recruited in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and Company C was recruited in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. And so, Corporal William H. Rihl, a 20-year-old Philadelphia native serving in a New York regiment, became the first Union soldier to die in combat above the Mason-Dixon Line.

Corporal Rihl, a gardener, and described as being 5’ 6 ¼” tall with dark hair, blue eyes, and a fair complexion, was buried by Confederate soldiers alongside the road where he fell in combat. His remains were soon moved to a nearby cemetery but later moved again in 1886 back to the site where he was killed, with the grave marked by the monument you see below roughly 1 mile north of Greencastle on the west side of U.S. Route 11:

(William Fleming farmhouse and PHMC marker© used with permission*)

(Image courtesy of Tower Bank of Greencastle** and Mark Twain Noe)* The historical marker is a registered trademark of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission and the marker text is copyright protected. Used with permission.

** A division of Graystone Tower Bank

The first Confederate soldier killed in Pennsylvania during the Gettysburg CampaignThe first Confederate soldier killed in Pennsylvania during the Gettysburg Campaign was apparently a victim of “bushwhacking” and not actual combat. On the afternoon of June 23, a week prior to the battle, Company D of the 14th Virginia Cavalry Regiment in General Albert G. Jenkins' Brigade was conducting reconnaissance and foraging in the area of Caledonia east of Chambersburg near the Cashtown Pass. As they approached the Cashtown Pass, the Confederate cavalry discovered a roadblock of felled trees and other debris blocking the road. Not long after clearing the obstacles and continuing eastward, a gun blast from the thick woods hit Private Eli Amick, who died later that day.

According to local history, Cashtown area resident Henry Hahn was the head of a small group of men who had waited to ambush the Confederates along the road, and after the war he confessed to being the one who shot Private Amick.

Private Eli Amick, a 42-year-old veteran of the Mexican War, was once suspected by Union troops as a “bushwhacker" himself -- he and his cousin Noah Probst were captured near their homes by Union troops in late 1861 while guarding the Wilderness Road. Accused of bushwhacking, they were released in the Spring of 1862, with Eli later enlisting in the 14th Virginia Cavalry Regiment in November of 1862. Another small example of the irony of war, don’t you think ??

The last soldier found on the battlefieldBelieve it or not, the remains of a soldier killed during the battle was found on March 19, 1996, wedged in the rocks on the southeast bank of the famous "railroad cut," one of the many scenes of severe fighting on July 1. Prior to that time, other remains were found in 1939 and 1914, and were also attributed to the battle.

After a five-day archaeological excavation, as well as lengthier testing and research, the National Park Service concluded the human remains (found in the vicinity of the tiny orange arrow in the right photo) were most likely a Confederate soldier from the 2nd Mississippi Infantry Regiment, which had seen action there:

Following a proper military ceremony, this last ??? soldier found on the battlefield was buried later that year in the Soldiers' National Cemetery in the vicinity of the New York State Memorial:

To read more about this truly amazing discovery and subsequent events, obtain a copy of the booklet published in January of 2009 sponsored by the National Park Service entitled “For the Sake of the Living: A Civil War Battlefield Burial” written by Benjamin Resnick, Douglas Owsley, and Susan Frankenberg.

One soldier still on the battlefield ???According to what I have read in various sources, there may still be more than 1,000 dead Union and Confederate soldiers still buried throughout the battlefield and surrounding areas. One of them is Private Isaac L. Taylor, a member of the 1st Minnesota Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel William J. Colvill. Private Taylor was a casualty of their famous charge on July 2 which decimated his regiment but helped to buy valuable time for the Union troops on Cemetery Ridge to regroup.

His brother Patrick was also a Private in the regiment and buried Isaac in a field north of the stone wall running east to west and just north of Pleasonton Avenue. It is my understanding that there is no record that his body was ever relocated to the Soldiers’ National Cemetery (although he may have been buried as an “Unknown”) or to his native Minnesota, so it is entirely possible that Private Isaac Taylor is still lying in eternal rest on the battlefield in the general area where he was killed. If you visit the Pennsylvania Monument and explore this area (the stone wall is roughly 60 yards north of the “T” intersection of Humphreys Avenue and Pleasonton Avenue), you may sometimes see a small U.S. flag along that same stone wall as a memorial to Private Isaac L. Taylor of the 1st Minnesota Infantry Regiment:

To learn more about Private Isaac L. Taylor, his brother Patrick, and all the other brave men (including many individual photographs) of the 1st Minnesota Infantry Regiment, go to the website at http://www.1stminnesota.net.

Veterans of Company A of the 1st Minnesota Infantry Regiment – 1897

(Photo courtesy of Mike Waricher)

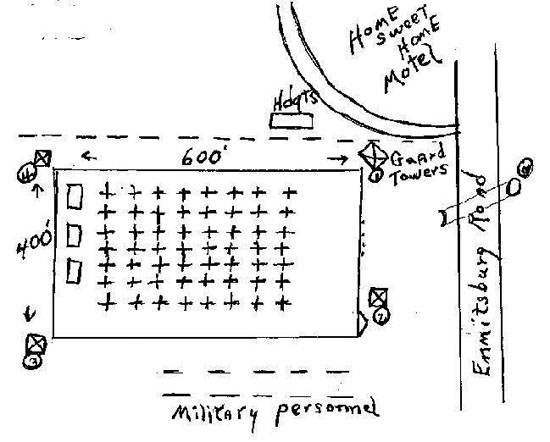

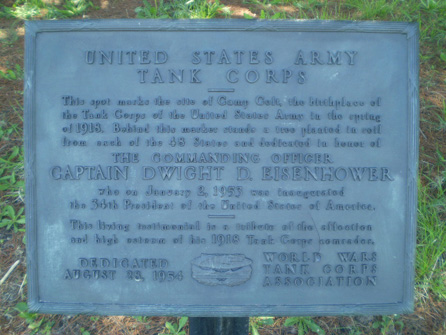

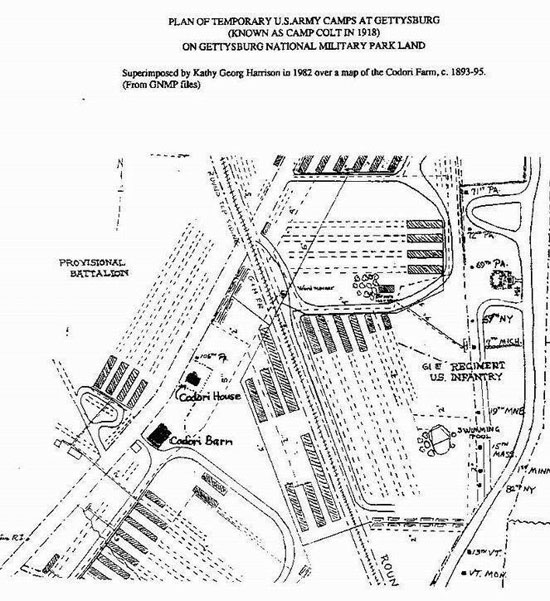

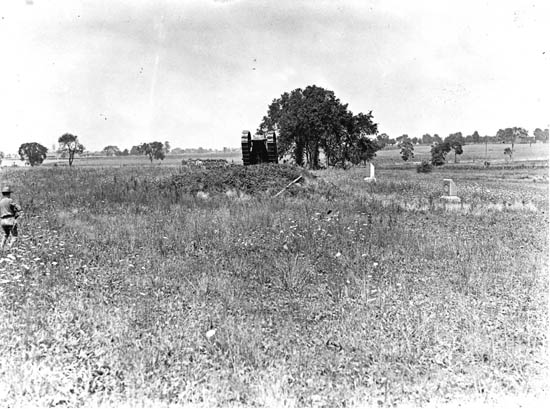

Camp ColtAs surprising as it may be to believe that a trolley line and three amusement parks once existed on a portion of the battlefield, it is perhaps just as surprising to learn that Camp Colt, a World War I era training camp for tanks, actually existed on much of the very ground of Pickett's Charge. In fact, it is my understanding from a conversation with a park ranger that because of this, the terrain of a large part of this hallowed area was changed through grading and excavation, so what we see today is not exactly the same identical terrain those gallant men marched across on their way to the Emmitsburg Road. Another interesting fact is that a young Army captain by the name of Dwight D. Eisenhower was the commander of the camp. During World War II, a POW camp housing approximately 300 German prisoners was located on the former site of Camp Colt. Today, all that remains of the site is a commemorative tree and a small marker along the Emmitsburg Road in the general location of the 192-acre camp:

(Sketch courtesy of the GNMP)

(Photo courtesy of Mike Waricher and the GNMP)

(Photo courtesy of the GNMP)

(Photo courtesy of the Eisenhower National Historic Site and Stacy Kilts)

What might have been lostSpeaking of World War II, according to the GNMP’s 1943 “Preliminary Report on Non-Ferrous Metals in the Gettysburg National Military Park”, World War II almost brought an end to all the metal monuments at Gettysburg. Approximately 18 tons of miscellaneous metal, obsolete signs, iron fencing, and worn out equipment had already been donated on September 11, 1942 to the federal government’s scrap metal drive as well as 38 tons of post-Civil War cannon balls. In addition, GNMP Superintendent J. Walter Coleman, who had been designated in 1941 as supervisor for the scrap metal drive in Adams County and was required to provide a list of scrap items immediately available on Federal property as well as the inventory of other metal objects that could be taken in case of need. As seen in the letter below:

October 13, 1942

Memorandum for the Director, National Park ServiceWe are enclosing herewith a newspaper clipping and photographs pertaining to our contributions to the salvage drive. This was handled by sale to the highest bidder because of the difficulty and expense which would have been involved if we had transported it ourselves.

A portion of this metal was sold on September 11 and consisted of 18 tons of miscellaneous metal, obsolete signs, iron fence, and worn out equipment. At the same time, and in addition to the 18 tons, we sold a pick-up truck, one motorcycle, one tar heater, one sedan, and one panel-body truck.

Having later received clearance for the disposition of the ornamental cannon balls removed from the field about eight years ago, we awarded a contract for this metal on October 7. This metal weighed approximately 38 tons. The cannon balls were almost entirely of a type larger than any used at Gettysburg, were cast after the Civil War, and were placed on stone pedestals along the Park roads.

We have continued our survey of metal that might be contributed and we have decided that a portion of the pyramidal piles of round and cylindrical shells placed beside each cannon the field can be removed without serious interference with the visitor’s understanding of the battle. Most of our cannon on the field occur in pairs or larger groups and it is our intention to remove half the shell pyramids. The survey indicates that 194 piles, weighing a total of approximately 60,000 pounds can be obtained.

The metal markers on this field indicate definite troop positions and are not primarily interpretive or story telling. Most of them are bronze markers on granite pedestals and we do not believe that they should be disturbed if this action can be avoided. There are, however, 19 Union and Confederate bronze itinerary tablets which could be replaced with a simple painted sign and map. If the shortage of bronze becomes more acute, these tablets may be turned in. If you wish us to do this at once, please do advise.

According to present indications, our total contributions should be in excess of 200,000 pounds of metal.

J. Walter Coleman,

SuperintendentSuperintendent Coleman’s priority list was submitted on January 19, 1943:

1. Itinerary markers; 231 pounds each.

2. 197 cannons; 229,300 pounds.

3. 256 position markers; 59,163 pounds.

4. Bronze on monuments; 20,950 pounds.

5. Statues; 57,800 pounds.

6. Inscriptions on monuments; 53,344 pounds.

7. Artistic reliefs on monuments; 4,254 pounds.

8. Portraits on monuments; 141,674 pounds.

9. Virginia, North Carolina, and Alabama Memorials; 48,500 pounds.Fortunately, the tide of World War II started to turn in favor of the Allies in 1943 and the list was not implemented. A special thanks to John Gaile and former GNMP Ranger/Historian John Heiser for sharing their information on this “monumental” topic !!!

Congressional Medal of Honor recipientsIt may be interesting to know that the Medal of Honor originated in 1862, and of the 1,520 awarded for action during the Civil War, there were 64 awarded for action at the Battle of Gettysburg, including Colonel Joshua L. Chamberlain and also General Daniel E. Sickles (Sickles and Chamberlain were awarded their medals about 34 years after the battle, when Congress authorized officers and not just enlisted men to be eligible for the Medal of Honor).

One of these 64 recipients, Captain William E. Miller, of Company H, 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment, is actually buried in the Soldiers' National Cemetery right along a main path near the New York State Memorial:

Captain Miller was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for helping to repel the Confederate cavalry charges under General J.E.B. Stuart's command roughly 3 miles east of Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 3.

(Photo courtesy of USAMHI)It is interesting that early in 2010, the U. S. Army recommended that the Medal of Honor be posthumously awarded to Lieutenant Alonzo H. Cushing of the 4th U.S. Artillery, Battery A (see the “Individuals” section on my “Off the Usual Path” page), who was mortally wounded on July 3 while helping to repel Pickett’s Charge, 147 years after the battle !!! The recommendation was eventually approved by Congress and on November 6, 2014 at the White House, the Medal of Honor was posthumously awarded to First Lieutenant Alonzo H. Cushing. The Medal of Honor was presented to descendants of Lieutenant Cushing’s brothers. Lieutenant Alonzo H. Cushing thus became the 64th Union soldier who was awarded the Medal of Honor for their gallantry at the Battle of Gettysburg.

(Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society)For more information on all of the 64 recipients and their citations for gallantry, visit the webpage at http://thomaslegion.net/battleofgettysburgmedalofhonorrecipients.html or the webpage at https://gettysburg.stonesentinels.com/the-medal-of-honor-at-gettysburg.

Confederate Medal of Honor recipientsPerhaps an even lesser known fact is that the South also has its version of the Medal of Honor which, due to financial issues and disagreements, was never awarded during the Civil War. However, the Sons of Confederate Veterans followed through with the idea and in 1977 posthumously awarded the first Confederate Medal of Honor. Since then, 54 medals have also been awarded, 6 of which were awarded for action during the Battle of Gettysburg:

Brigadier General Richard B. Garnett (Pickett's Division, I Corps) -- killed in Pickett's Charge on July 3

Brigadier General Wade Hampton (Stuart's Cavalry Division) -- for action on July 3

Colonel Henry K. Burgwyn, Jr. (26th North Carolina Infantry Regiment) -- killed on July 1

First Lieutenant William A. McQueen (Garden's Battery, Palmetto Light Artillery) -- for action on July 3 in support of Pickett's Division

Private Wilson J. Barbee (1st Texas Infantry Regiment) -- wounded several times during action on July 2 at Devil's Den

Color Sergeant George A. Branard (1st Texas Infantry Regiment) -- for action on July 2 at Devil’s Den

For a list of all 54 recipients, their units or ships, and fields of battle (land or sea), go to the webpage at http://thomaslegioncherokee.tripod.com/confederaterollofhonor.html.

The Rebel "yell"Everyone has read about or heard the famous Rebel "yell" in television shows or in movies, but now you can hear for yourself an authentic Rebel "yell" by a 95-year-old Confederate veteran that was recorded in 1935. I learned about this when I read a newsletter of the Civil War Round Table of Gettysburg, which had information from an article of the June 2008 issue of The Civil War News. To read more about this unique opportunity to go back in time to hear a real Rebel "yell" (a short and a long version), go to http://www.26nc.org/History/Rebel-Yell/rebel-yell.html. To read and hear more, go to http://senseofevents.blogspot.com/2011/04/authentic-rebel-yell.html. When you listen, imagine hearing that sound repeated by hundreds or thousands of Confederate soldiers ...

The "Stonehenge" of the battlefieldOne of the lesser known mysteries of the battlefield surrounds a small assortment of 12 or so footstool sized stone blocks of various shapes and colors. They are all "arranged" in somewhat of a circular pattern with one block in the middle, and the area is nicknamed the "Stonehenge" of the battlefield. To get there, park in the small "turnabout/parking area" on the north side of Wright Avenue roughly .3 of a mile east of Big Round Top. Then take a barely visible footpath to the left of the rock at the edge of the woods (see the photo below on the left) and go about 20 yards:

Many theories abound as to where these stone blocks came from and their original purpose, but to this day, none of the Park Rangers or Licensed Battlefield Guides seem to really know for sure. What I find particularly interesting are the three identical semi-curved blocks that contain a small 3-inch long slot that is approximately 3 inches deep --- were they part of an arch or a column, or even an old drainage culvert, or were they simply "factory rejects" discarded out of sight?

After doing a fair amount of research (onsite and computer), I have come up with my own theory. To make a long story short, I believe that the stones, or at least the three similarly sized semi-curved stones like the one pictured above, were extras or "factory rejects" for a portion of the tower of the monument to the 12th and 44th New York Infantry Regiments located on the summit of Little Round Top. The dimensions, inner and outer arcs, and textures (rough exterior and smooth interior) match some of the blocks just above a more decorative level approximately halfway up the tower. Here are just some of the photos I took to support my theory:

(cardboard template of the inner arc from the three semi-curved stones at "Stonehenge")

There is another area nearby which is also referred to the “Stonehenge” of the battlefield. Located roughly 10 yards to the west of the monument to the 49th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment about halfway down on the north side of Howe Avenue is a collection of layered stone slabs approximately 6 feet by 11 feet in size. Theories as to what it is range from it being an elaborate drainage culvert (but there is no other similar one that has been found anywhere on the battlefield) to it being the original location of the monument to the First Vermont Brigade (see the “Unusual monuments” section on my “Something Different” page).