Battle of Gettysburg Buff

A website for Civil War

buffs interested in the

Battle of Gettysburg

Something Different

No matter how many times I tour the battlefield, I never fail to always find something different to see or learn about:

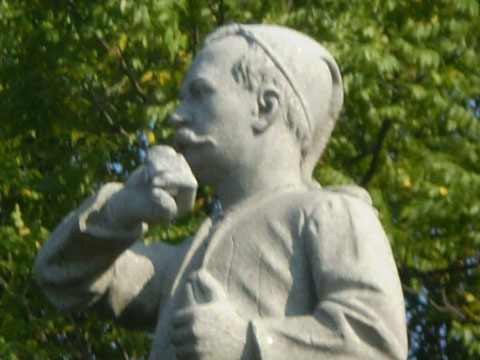

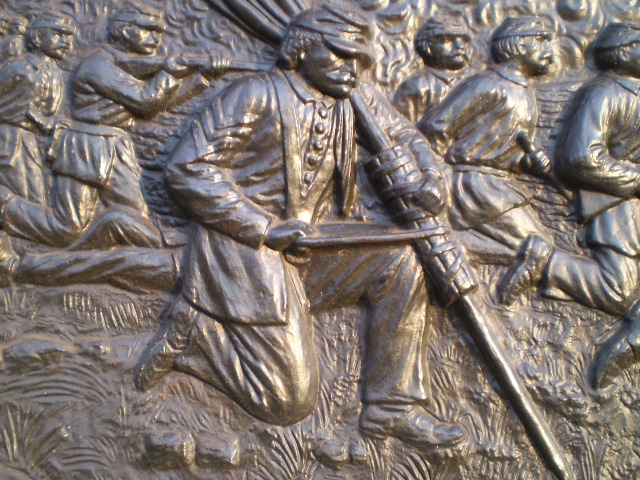

Faces of the battleAlong with the statues (equestrian or otherwise) of specific generals or colonels, many of the monuments contain the faces of actual soldiers who served with a particular regiment. Some of them are carved in stone and some of them are depicted in bronze, but a lot of them were real people nonetheless. In addition to the bronze depiction of General George Armstrong Custer on the monument to the Union cavalry regiments from Michigan which saw action on July 3 at the East Cavalry Battlefield (see my "Off the Usual Path" page), perhaps the most well-known bronze face is that of Colonel Patrick H. O'Rorke on the monument to the 140th New York Infantry Regiment on the summit of Little Round Top, who was killed on July 2 while defending the right flank of that hill:

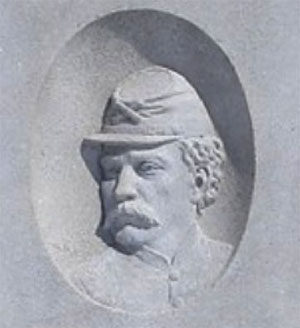

Another similar monument can be found on the west side of the northern slope of Little Round Top, and it is the monument to Colonel Emory Upton and the 121st New York Infantry Regiment:

A monument that depicts two Union officers, both of whom were wounded during the battle, can be found on the southern half of the summit of Little Round Top inside the “castle” monument to the 12th New York and 44th New York Infantry Regiments (see my “Odds and Ends” page). General Daniel A. Butterfield (shown in the bottom left photo), General Meade’s Chief of Staff at Gettysburg, had been a colonel in the 12th New York Infantry Regiment as well as a former brigade commander of the 44th New York Infantry Regiment; General Francis C. Barlow (shown in the bottom right photo), commanding the First Division of the Union XI Corps at Gettysburg, was also a former officer in the 12th New York Infantry Regiment:

Another monument that depicts two Union officers (although only one of them was present at Gettysburg) is the monument to the First New Jersey Brigade, which consisted of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 15th New Jersey Infantry Regiments. The monument, located roughly 65 yards off to the east side of Sedgwick Avenue south of the intersection with United States Avenue, contains the likeness of its commander at Gettysburg, General Alfred T. A. Torbert, and of its original commander, General Philip Kearney:

Another similar monument to a Union colonel who also paid the supreme price that day on July 2 but while defending Cemetery Ridge is the one to Colonel George H. Ward and the 15th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. However, this monument, located about 100 yards north of the Nicholas Codori farm along the east side of the Emmitsburg Road, is situated roughly 40 yards inside a wooden fence and is very seldom noticed, let alone visited:

A monument to yet another Union colonel who also gave his life that day on July 2 is the handsome stone monument to Colonel Harrison H. Jeffords and the 4th Michigan Infantry Regiment at the southern end of the Wheatfield. Located at the "T" intersection of De Trobriand Avenue and Sickles Avenue, this beautifully carved monument shows Colonel Jeffords with the regimental flag he died defending, having been bayoneted after refusing to surrender it:

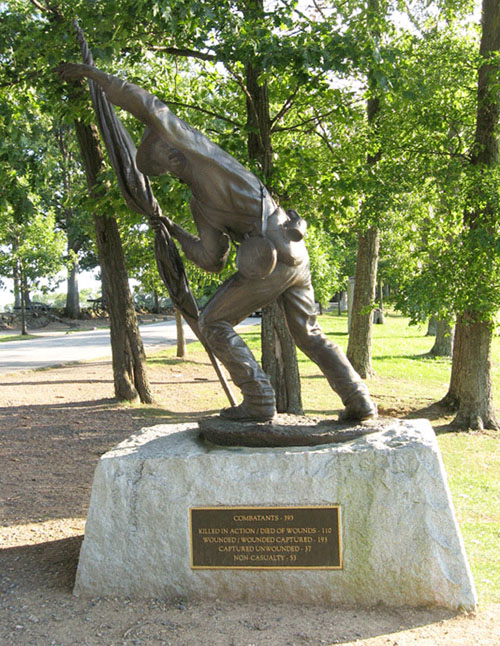

A similar stone monument is located at the southwest corner of the intersection of Reynolds Avenue and the Chambersburg Pike (Route 30) and which memorializes the heroics of Sergeant Benjamin H. Crippen and the 143rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment during their retreat on July 1. Color Sergeant Crippen, as the documented story goes, stopped several times during his regiment's withdrawal from McPherson's Ridge that afternoon to defiantly shake his fist at the oncoming Confederate soldiers, and was eventually shot and killed. An almost identical story is also told about Color Sergeant Samuel L. Peiffer of the 150th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment that day, but it is Sergeant Crippen who is forever immortalized in stone along the Chambersburg Pike:

Nearby is another similar monument, and it is located along the east side of Buford Avenue at the intersection of the Mummasburg Road. The monument to the 17th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment depicts Private George W. Ferree:

A monument to a fallen Union hero of July 3 is the monument to Colonel Eliakim Sherrill and the 126th New York Infantry Regiment, located in Ziegler's Grove on Cemetery Hill roughly 100 yards north of the Abraham Brian house:

A bronze statue depicting an actual lower-ranking officer can be found on Cemetery Ridge along the east side of Hancock Avenue roughly 200 yards south of the famous “copse of trees” is on the monument to the 13th Vermont Infantry Regiment. The officer depicted is Lieutenant Stephen F. Brown:

Lieutenant Brown, although previously under military arrest for disobeying an order (he went to get water for his men during the hurried march to Gettysburg), joined the fray with a hatchet in his regiment’s attempt to help repel Pickett’s Charge on July 3. However, the hatchet was not deemed appropriate to be included prominently on the monument (“political correctness” Civil War style ???), so he appears with a typical sword in hand. The hatchet is indeed depicted on the monument, but is placed at his right foot:

Just a short distance further up Cemetery Ridge along the east side of Hancock Avenue just north of the famous “copse of trees” is a monument to the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment. The kneeling soldier depicted is Private Joseph H. Lindemuth:

Several stone statues which depict actual Union Privates can also be found throughout the battlefield, and one can be found on Culp’s Hill. About one-third of the way up from Spangler’s Spring on the left side of Slocum Avenue and roughly 40 yards past the statue of General John W. Geary is the monument to the 23rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, also known as “Birney’s Zouaves.” The soldier depicted is Private Matthew Spence, who is partially clothed in a regular Union uniform because the regiment had switched from the Zouave uniform style long before the Gettysburg Campaign:

Another stone statue depicting a Union Private can be found on the northern half of the summit of Little Round Top. The monument to the 155th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment depicts Private Samuel W. Hill:

What is interesting to note is that Private Hill is wearing the uniform of a Zouave, which the regiment did not switch to until 1864. That is in curious contrast with the story behind the monument to the 23rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment mentioned above. For more information, see the “Chasseurs and Zouaves” section on my “More Odds and Ends” page.

Just a few yards south of the famous “railroad cut” along the west side of Reynolds Avenue is the monument to the 84th New York Infantry Regiment (better known as the 14th Brooklyn Regiment). The monument depicts Lieutenant Harry W. Mi(t)chell, who was wounded during the battle:

Nearby on the east side of Oak Ridge below the observation tower along Robinson Avenue is the monument to the 13th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, depicting a color sergeant of the regiment who was reportedly killed on that very spot, Sergeant Roland B. Morris:

Located on the west side of Wainwright Avenue on East Cemetery Hill approximately 200 yards north of the “T” intersection with Slocum Avenue and roughly 50 yards east of the equestrian monument to General Oliver O. Howard is the monument to the 54th New York Infantry Regiment, commanded by Major Stephen Kovacs. In addition to seeing action on July 1 near Barlow’s Knoll (see the “Advanced positions” section on my “Off the Usual Path” page), the regiment was attacked on Cemetery Hill late in the day on July 2, during which Color Sergeant Heinrich Michel was killed and is now immortalized on the monument:

Another interesting fact about the 54th New York Infantry Regiment is that not only were their uniforms originally black and silver, but they also carried a black “pirate’s flag” complete with skull and crossbones into battle until the Spring of 1862 !!!

A color sergeant of the 149th New York Infantry Regiment, Sergeant William C. Lilly, is depicted on the small bronze plaque on the front of the regiment’s monument located on the right side of Slocum Avenue roughly 80 yards past the statue of General John W. Geary as you ascend Culp’s Hill. Sergeant Lilly is shown mending the flagstaff with boards from a cracker box and straps from his knapsack during the fighting on July 2 when the flagstaff was shot in half:

A Union artilleryman, Lieutenant Edward M. Knox, is depicted on the monument to the 15th New York Independent Battery commanded by Captain Patrick Hart. It should be noted that Lieutenant Knox was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroism on July 2 during the fighting near the Peach Orchard. The monument is located on the north side of the Wheatfield Road just east of the Peach Orchard and roughly 200 yards east of the Emmitsburg Road:

Yet another Union artilleryman is depicted on the monument to Battery B of the 2nd Maine Light Artillery. The face is reportedly that of the battery’s commander at the time of the battle, Captain James A. Hall. The monument is located north of the Chambersburg Pike between the equestrian statue of Union General John F. Reynolds and the statue of Union General John Buford directly across from the “T” intersection with Stone Avenue near the Edward McPherson barn:

(Photo courtesy of the USAMHI)

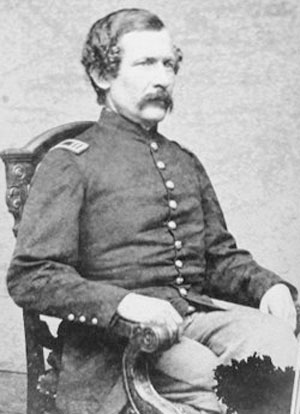

A Union cavalry officer, Major William Wells, commanded a battalion of the 1st Vermont Cavalry Regiment and participated in General Elon Farnsworth’s ill-fated cavalry charge against the right flank of the Confederate Army near the base of Big Round Top and the John Slyder farm on the afternoon of July 3 after Pickett’s Charge had been repulsed. For his bravery and gallant actions that day, Major Wells was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor (for more information on that ill-fated charge, see the “The South Cavalry Battlefield --- the other cavalry action on July 3” section on my “Off the Usual Path” page). The monument is located on the south side of South Confederate Avenue roughly 60 yards before you cross the bridge over Plum Run:

For more information on these monuments, I strongly recommend reading the book “Gettysburg: Stories of Men and Monuments” (see my “Books Worth Reading” page).

So, the next time you look at a monument with a soldier's face, you may be looking at someone who was actually there during those fateful days in July of 1863:

Regimental animal mascots and monumentsIn addition to many regiments, both North and South, having dogs as official or unofficial mascots, there were other unusual mascots throughout the war, including a sheep, donkey, badger, raccoon, an eagle, a bear, and a camel. General Robert E. Lee had a "pet" chicken which provided him with fresh eggs but was AWOL for a short period of time during the Battle of Gettysburg, reportedly causing him much consternation.

Two monuments at Gettysburg have the likeness of their military unit's mascots depicted on them: the 11th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, and the 69th New York Infantry Regiment, one of the regiments of the famous "Irish Brigade." The back of the 11th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment monument, located on Doubleday Avenue south of the observation tower on Oak Ridge, honors the memory of their beloved mascot, Sallie. When the Union line collapsed north of town on July 1 and the men of the 11th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment eventually regrouped on Cemetery Hill, Sallie was among the missing. However, when members of the regiment returned on July 5 to Oak Ridge to bury their dead from the first day's fighting, Sallie was still there, watching over and guarding the dead and wounded. Sadly, Sallie did not survive the Civil War; she was shot in battle at Hatcher's Run, Virginia, in February of 1865. Like her masters, she is gone but not forgotten.

The 69th New York Infantry Regiment, one of the regiments of the Second Brigade (also known as the "Irish Brigade"), First Division, of Major General Winfield Hancock's II Corps, adopted two Irish wolfhounds that often wore green coats with the number "69" emblazoned in gold:

The monument is located west of the Wheatfield on the south side of Sickles Avenue as you approach the uphill loop in the road. To learn more about the regimental mascots of the Civil War, go to the webpage at http://alexandriava.gov/historic/fortward/default.aspx?id=40198. To read a wonderful book about many of the dogs that served as mascots, some of which also lost their lives in combat, I highly recommend “Loyal Hearts: Histories of American Civil War Canines” by Michael Zucchero. According to Private William F. Fulton of the 5th Alabama Infantry Battalion in General James J. Archer’s Brigade, the first Confederate casualty as their skirmish line encountered Union cavalry pickets that fateful morning of July 1, 1863 at Gettysburg was not a Rebel soldier but a nameless little dog that had been adopted by Company A.

Other monuments with animalsIn addition to the two monuments that are mentioned at the top of this page, there are many, many other monuments with animals depicted on them in some fashion. Of course, there are several monuments with eagles "perched" atop them that can be found throughout the battlefield, but there are a few monuments with more unusual animals carved, perched, or depicted on them, including a wildcat, owl, lion, rooster, and a buffalo!!!

Located along the east side of Emmitsburg Road at the intersection of United States Avenue (about 200 yards north of the Peach Orchard) is the monument to the 105th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, whose nickname was the "Wild Cat Regiment":

If you head over to Culp's Hill, you can find the owl, rooster, lion, and the buffalo. To find the owl, take Geary Avenue (the road to the left as you leave Spangler's Spring) around the bend and below Pardee Field (see my "Off the Usual Path" page). Look off to the left side of the road for the large monument to the 5th Ohio Infantry Regiment and you will see the owl at the top:

In addition, if you walk into the woods about 25 yards behind the monument, you will also find a small plaque on a boulder containing an owl:

If you take Slocum Avenue (the road to the right as you leave Spangler's Spring) and head on up toward the top of Culp's Hill, look off to the right side of the road for the monument to the 7th Ohio Infantry Regiment. You will have to walk around to the back of the monument to find the bronze plaque with the rooster:

Continuing up Slocum Avenue, look again on the right side of the road for the monument to the 78th and 102nd New York Infantry Regiments. It is said that if you look very carefully on the one side of the monument (see the photo on the left below), you can see the head and a paw of a lion:

What I also noticed, though, is that on one side of the monument it reads "78 & 102 N.Y. INFTY", but the opposite side reads "102 & 78 N.Y. INFTY" --- equal billing, perhaps ??? It could also be related to the fact that those two regiments were intermingled during at least part of the fighting on Culp’s Hill.

Upon reaching the summit of Culp's Hill, look for the monument to the 7th Indiana Infantry Regiment located across from the observation tower. You will find a circular carving with shapes seen on the State Seal of Indiana depicting, among other things, a buffalo:

Since insects are technically animals, I have included the monument to Companies E and H of the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters Regiment, which is located on the John Slyder farm at the southern end of the battlefield roughly 650 yards east of the Emmitsburg Road. The monument includes the depiction of a hornet’s nest because one Confederate officer’s report described the action as “encountering a perfect hornet’s nest of sharpshooters” when General Evander Law’s Brigade ran into these Union troops on July 2:

Located along the east side of Doubleday Avenue on Oak Ridge, the monument to the 90th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment is in the shape of a tree and includes a bird nest (for more information on the interesting story behind this monument, see the “Unusual monuments” section on this page):

If you look closely, a butterfly can be found on the “Friend to Friend” Masonic Memorial located in the Soldier’s National Cemetery Annex at the intersection of Steinwehr Avenue and Taneytown Road:

This section would not be complete without mentioning the dove (symbolizing the dove of peace) which can be found on the Louisiana State Monument located along the east side of West Confederate Avenue on Seminary Ridge roughly 150 yards north of the intersection with the Millerstown Road:

General Barksdale's devoted dogSpeaking of dogs, I came across a story about Confederate General William Barksdale, one of the brigade commanders in Major General Lafayette McLaw's Division of Lieutenant General James Longstreet's I Corps. General Barksdale was severely wounded and captured on July 2 and taken to the Joseph Hummelbaugh farmhouse behind the center of the Union lines. General Barksdale later succumbed to his wounds on July 3, and was buried there until his wife traveled to Gettysburg after the war with her husband's favorite hunting dog to retrieve his remains. The story goes that the dog refused to leave the gravesite even after the body was exhumed and loaded for transport home to Mississippi, and remained there at the gravesite even after repeated attempts the next day by Mrs. Barksdale to get the dog to return home with her and her husband's remains. For days afterward, the loyal dog refused to budge and turned down all offers of food and water from everyone, eventually dying on his master's former grave. As the years passed, it was said that a howling dog could often be heard at the Hummelbaugh farm, and especially on the nights of July 2 and 3, the anniversary of General Barksdale's wounding and death. Whether the tale of a "ghostly" dog is true I will not speculate upon, but I can believe the part of the story about a devoted and loyal dog. Devotion and loyalty are not limited to mankind, especially soldiers devoted and loyal to a cause, are they?

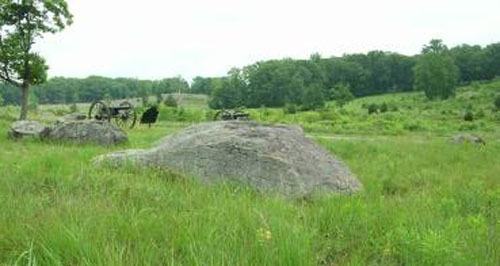

Rock formationsIn addition to the huge boulders on the battlefield that are well known as Devil's Den, there are a few other interesting locations or rocks in the same vicinity. Shown below are three of them:

elephant rockAlong with Devil's Den itself, there are two other large rocks in that vicinity worth looking for. One is the so-called "elephant" rock (the rock in the middle in the photograph above), because of its similarity in shape and size to an elephant. It is located just to the south of Devil's Den just as you make the turn upward toward the crest of Devil's Den where the monument and cannons of Captain James E. Smith's 4th New York Battery are located. It is interesting to me that soldiers during the Civil War, when they experienced combat for the first time, were said to have "seen the elephant" --- I have often wondered how many soldiers literally "saw the elephant" near Devil's Den during the battle?

trough rockThe other rock is commonly referred to as the "trough" rock, with a large depression, either natural or man-made, where a horse could get a drink. I am unsure when this rock was discovered or first used as a trough, but I have seen one old photograph in the book "Devil's Den: A History and Guide" that shows a horse and rider using it for that purpose. In any event, it is located up the footpath to the left across the bridge over Plum Run and worth taking a look.

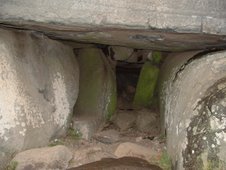

The Devil's "Den"This so-called entrance to the Devil's "den" is approximately 50 yards up and to the left of the National Park Service's "Devil's Den" sign located across from the parking area. I have seen a few people crawl inside with a flashlight, and it appeared to be at least 6 feet by 8 feet wide but only 2 feet high. However, I would not at all recommend going in there because of the possibility of disturbing any snakes that might be living or perhaps hibernating there.

To learn more about Devil's Den and the surrounding area, I would highly recommend the book "Devil's Den: A History and Guide" by Garry E. Adelman and Timothy H. Smith (see my "Books Worth Reading" page).

The Devil's BathThe so-called Devil’s Bath is located approximately 20 yards up and to the left of the National Park Service's "Devil's Den" sign located across from the parking area:

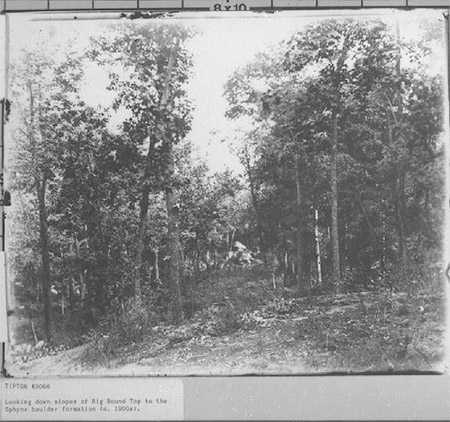

The “Sphinx”The “Sphinx” of the battlefield is located on the eastern slope of Big Round Top about 400 yards along the old horseback/hiking “Loop Trail” from a starting point just behind the monument to the 10th Pennsylvania Reserves, which is located roughly 50 yards south of the intersection with Wright Avenue. The rock formation is about 14 feet tall and is still marked along the path by a short round wooden post that used to denote “STOP # 6” on the National Park Service’s Nature Trail. As you can see in the bottom left photo, the “Sphinx” is very difficult to see during the spring or summer even though it is only 20 yards off the path; it is much more visible during the late fall (see the bottom right photo) or winter:

(Fall Sphinx photo courtesy of Lew and Ginny Gage)PLEASE BE VERY CAREFUL IF YOU GO OFF THE PATH ---

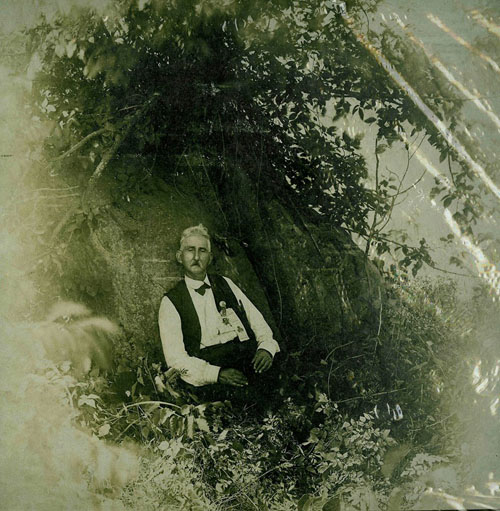

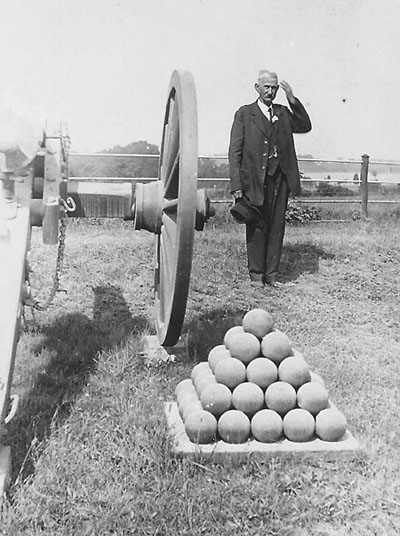

THE AREA IS THE “HOME” OF POISONOUS SNAKES !!!On a sad note, it was discovered that the “Sphinx” rock formation on Big Round Top was toppled by trees during a storm sometime in August or September. Due to its isolated position east of the parking lot on Big Round Top, it has not been determined exactly when or how the damage to the “Sphinx” occurred. Reportedly named by early battlefield guides (it was called the “Sphinx” as early as the 1900’s as shown in the William H. Tipton photo shown below), the “Sphinx” is sadly no longer:

(William H. Tipton photo from the 1900’s)

(October 30, 2021 photo)

The Devil's KitchenThe Devil's Kitchen is what I would consider a smaller version of Devil's Den but just as much fun to explore (remember to keep in mind that snakes may be present on or among the rocks and be very careful !!!). As I was climbing and crawling around this area in May, I passed in front of a tall but narrow crevice and felt cool air --- the "refrigerator", perhaps ???

To get to the Devil's Kitchen, park at the parking area near the base of Big Round Top and take the footpath on the left (on the same side of the road as the parking area, not up the hill toward the summit). Walk roughly 75 yards and you will see this rock formation on the right.

The Devil's SlipperThe Devil's Slipper is a pickup truck sized rock that apparently got its name (as have so many others) by the early tour guides (I read about and saw an old photograph of the Devil's Slipper in the 1895 Annual Report of the Gettysburg National Military Park Commission). In any event, it can still be found on the south side of South Confederate Avenue approximately 50 yards before the 3-car parking area across from the interpretative markers for the ill-fated July 3 Union cavalry charge by Brigadier General Elon J. Farnsworth (see my "Off the Usual Path" page). Please note that it is the rock in the background behind the tree and not the rock in the foreground.

Ledge of rocksThere is a “ledge of rocks” that is easily found which is mentioned in the Official Report of the 3rd Arkansas Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel Van H. Manning of General Jerome B. Robertson’s Brigade of General John B. Hood’s Division. Located roughly 30 yards off the west side of the road at the southeast corner/bend of Cross Avenue just before crossing the old trolley path (see the “The old trolley line” section on this page), this area was utilized by that regiment during the fighting against the 17th Maine Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel Charles B. Merrill and the 20th Indiana Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel John Wheeler (see the “Rock carvings and inscriptions” section on this page):

For more information, I recommend the book "The Wheatfield at Gettysburg: A Walking Tour" by Jay Jorgensen (see my "Books Worth Reading" page).

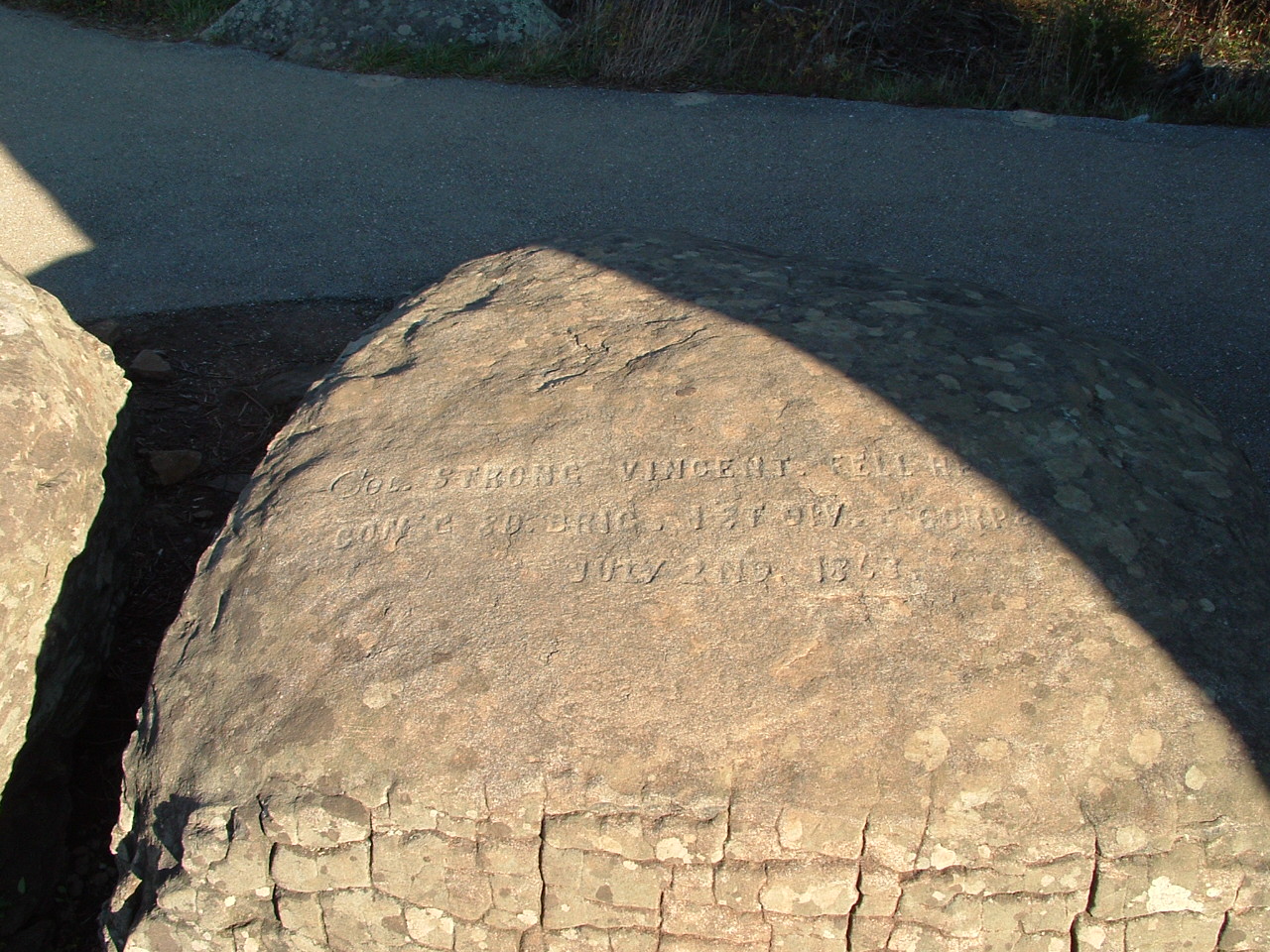

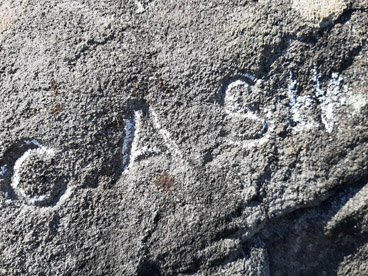

Rock carvings and inscriptionsAlthough some rock carvings are difficult to locate, some are not. Two of the easier ones to find are located on Little Round Top; while one is nearly illegible (see the photo on the left) which reportedly marks the spot where Colonel Strong Vincent, commanding the Third Brigade of the First Division of the Union V Corps was mortally wounded, and is located on a chest-high rock just a few feet to the north of the "castle" monument, it is still readable if the sun hits it just right (see the photo on the right). One is still easily discernible (see the bottom photo) on the back of the monument to the 91st Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment (the one between the cannons --- not the larger monument in front) clearly marking where Brigadier General Stephen H. Weed, the commander of the Third Brigade of the Second Division of the Union V Corps and Lieutenant Charles Hazlett, of Battery D, 5th U.S. Artillery, were killed within only moments of each other.

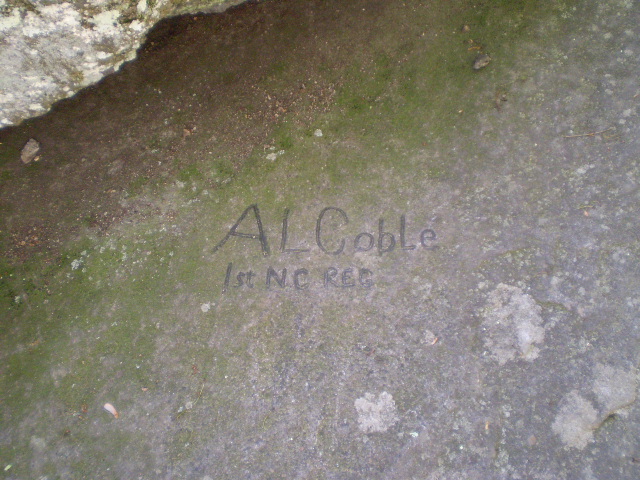

I have found a few more rock carvings, one near Spangler's Spring at the base of Culp's Hill and two near Devil's Den. To locate the rock carving of "AL Coble - 1st NC REG", park your car on East Confederate Avenue across from Spangler's Meadow (see my "Off the Usual Path" page) and walk toward the group of boulders at the base of the hill. Go around to the right and look in between the rocks for a flat area with the carving:

I have read that "AL" are initials, and the "A" stands for the soldier's first name - Augustus. An email to me from a descendent of this soldier has informed me that his full name was Augustus Lucian Coble, and he was from Alamance County.

(Photo courtesy of Ed Coble)

Other carvings can be found on Culp’s Hill a short distance in front of and also directly behind the monument to the 149th New York Infantry Regiment (see the “Faces of the battle” section at the top of this page). On a boulder about the size of a picnic table just 5 yards off the road between this monument and the nearby monument to the 122nd New York Infantry Regiment, you can find "P. SOCKS 1871" and "A.W. LIGHTNER 1871" (it is interesting to note that the letters "G" and "N" in "Lightner" are carved backwards):

(Computer enhancement by Tom Miller)

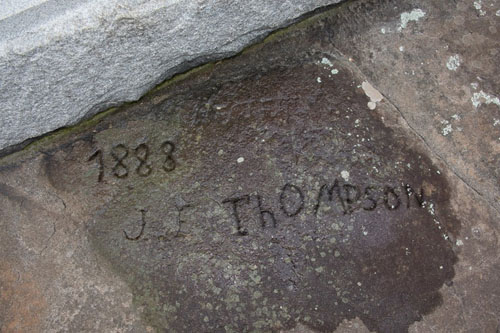

(Computer enhancement by Tom Miller)Behind the monument, you can clearly see the date "1888" and the name "J.E. THOMPSON":

(Computer enhancement by Tom Miller)Another carving on Culp’s Hill can be found on the top of the small boulder containing a plaque to the 84th New York Infantry Regiment (also known as the 14th Brooklyn). The carving indicates the year the plaque was dedicated:

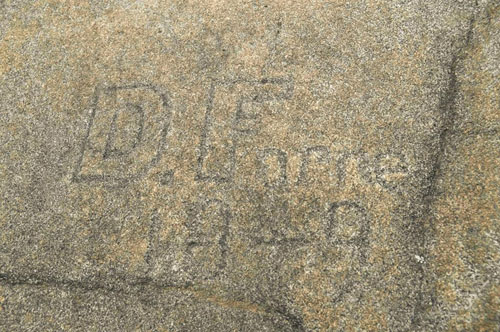

An interesting rock carving can be found on the summit of Devil’s Den on the flat sloped rock near the famous “sniper” pit:

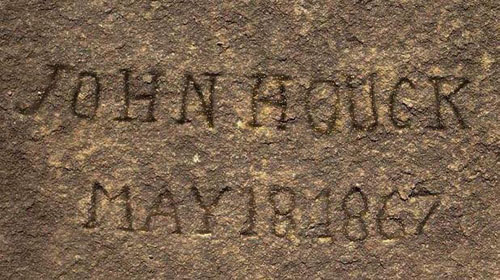

(Computer enhancement by Tom Miller)According to Licensed Battlefield Guide Tim Smith, the carving was apparently made by John Houck, a former owner of the land encompassing Devil’s Den.

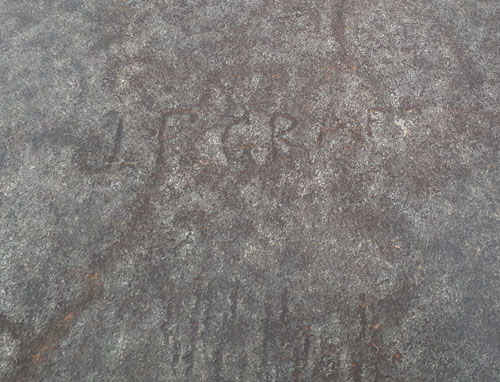

Also located nearby on the summit of Devil’s Den and about 30 yards to the southeast of the carving above and on top of the flat boulder across from the small wooden bridge is another carving that is often overlooked and unusual in that all of the letters are capital letters except one --- the second “t”):

(Photo courtesy of Mark Scygiel)With famous Civil War photographer and Gettysburg resident William H. Tipton’s battlefield studio originally located nearby, it is entirely likely that one of his relatives carved it, and I can find at least 9 candidates: James B. Tipton, James E. Tipton, James W. Tipton, John H. Tipton, John J. Tipton, John R. Tipton, John W. Tipton, and June F. Tipton. However, I contacted a good friend of mine who is a direct descendant of William H. Tipton, who informed me that she has no family information as to who made that carving.

What is also interesting is that there is another carving about two feet behind the carving above and is just as mysterious:

The letters appear to be “J F GRAF” but could possibly be “J F GRAFT”, “J P GRAF”, “J P GRAFT” or something similar. I have not yet found any accounts or records of a soldier (Union or Confederate) who might have made the carving or if it might have been a local civilian or tourist. Another rock carving mystery continues …

To find the rock carvings in Devil's Den, park in the main parking area there. Then cross the road and walk toward the right to find the monument to the 4th Maine Infantry Regiment. Located between the monument and the road (facing Little Round Top) is the rock carving "4TH ME":

To locate the other rock carving, cross the road and walk along Warren Avenue toward Little Round Top until you can walk over to the monument to the 40th New York Infantry Regiment located on your left. The rock carving is close by, and has the diamond insignia of the Union Army's III Corps:

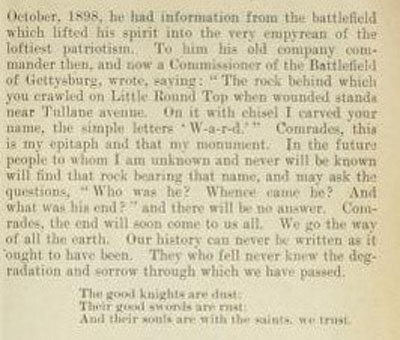

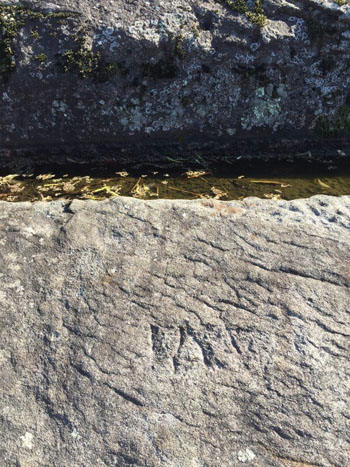

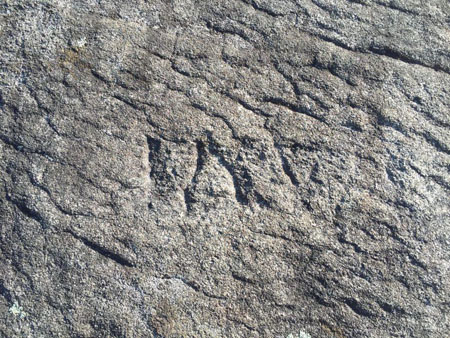

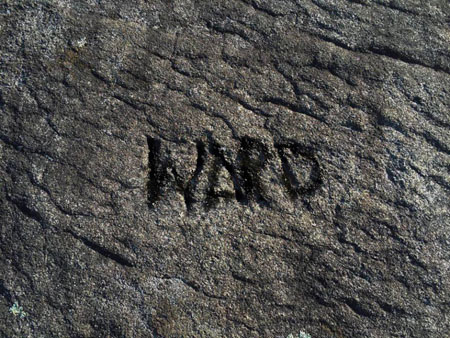

(Computer enhancement by Tom Miller)Located nearby on the famous “trough rock” (shown above in the "Rock formations" section) is what could be a famous carving made by Major William M. Robbins, a Confederate officer who commanded Company G of the 4th Alabama Infantry Regiment at Gettysburg and later served as a member of the Gettysburg Battlefield Commission from 1894-1905. According to a post-war article in Confederate Veteran magazine (Volume 8: 1900) written by Sergeant William C. Ward, a former soldier in Company G, he stated that Robbins had written to him and stated that he had carved W A R D on the boulder where Ward had crawled after he had been wounded during the Confederate assault on Little Round Top on July 2:

While “Tullane avenue” cannot be found on any map of the battlefield and is perplexing in efforts to determine the location of the carving, “trough rock” is not beyond the realm of possibility as to where Ward crawled to in order to get out of the line of fire after he was wounded.

After learning in January of 2022 about GNMP Ranger Chris Gwinn (Supervisory Park Ranger for the division of Interpretation and Education) and his February 18, 2022 program for the Harrisburg Civil War Round Table about William M. Robbins, I emailed Chris and asked him if he had heard of this and he had not. I shared with him my info about my research and on-site efforts with several fellow Battle of Gettysburg buffs in 2015 to try to find the carving. I also recalled that during one of our searches, team member (and photographer) Tom Miller discovered a carving on the famous “trough rock” in the area below Little Round Top. Tom later computer-enhanced the photo and shared it with the team, but I and everyone else felt at that time that the location was too far from the route where Ward and Robbins’ 4th Alabama Regiment advanced on July 2.

On a whim, I sent the photos (shown below) to Chris and also to former GNMP Ranger/Historian John Heiser (whom I had contacted back in 2015 about the story ---- John had heard the story and had also looked for it in the past but to no avail). After seeing these photos, John told me that “Although the boulder is not at Little Round Top per se, it certainly is within the general area where the 4th Alabama was engaged and not too far away from the 4th Alabama as anyone could have crawled away from the line of battle in any direction to escape the line of fire.” Chris also thinks it could be the carving as well --- you can decide for yourself:

(Computer enhancement by Tom Miller)I found two more in August of 2008, and they are perhaps two of the more difficult ones to find: the "D.A." rock and also the “flag” rock. The "D.A." rock marks the location where Captain David Acheson of the 140th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment was originally buried after being wounded several times during the fierce action that occurred on July 2 in and near the Wheatfield. To find this rock, park safely near the "T" intersection of Wheatfield Road and Crawford Avenue and then walk approximately 200 yards north along the dirt lane of the John Weikert farm. At the end of the lane (REMEMBER --- THE RESIDENCE IS ON PRIVATE PROPERTY), you will see a small white barn --- go behind the barn and walk approximately 100 yards west along an intermittent stone wall. The "D.A." rock will be on your right:

(Photo courtesy of John Banks)The other difficult one I found was the "flag" rock in the vicinity of Devil's Den. Located about 50 yards behind the "elephant" rock (shown above in the "Rock formations" section), the "flag" rock is the second of the two similarly sized boulders and is difficult to climb up on in order to see the carvings of not one but two flags: there is a small flag about 6" x 8" that is easy to see, but the larger flag about 36" x 36" is extremely worn and much more difficult to see. There are other carvings as well, including "U.F.S. 1873":

If you do attempt to climb this rock, be very careful and have someone with you to help you do so, but all of the carvings will be worth seeing, as well as the view from there of Devil's Den and Little Round Top (see the photo below):

It should be noted that “elephant rock” (shown above on this page in the "Rock formations" section) also has an interesting pre-war carving on top of it:

(Photo courtesy of Darah Gardner)The carving was possibly made by David S. Forney, son of Samuel and Eliza Forney of Gettysburg. In the 1850 census, David’s occupation is listed as "artist" and gives evidence that the area now known as "Devil's Den" was a popular spot for local residents even before the battle.

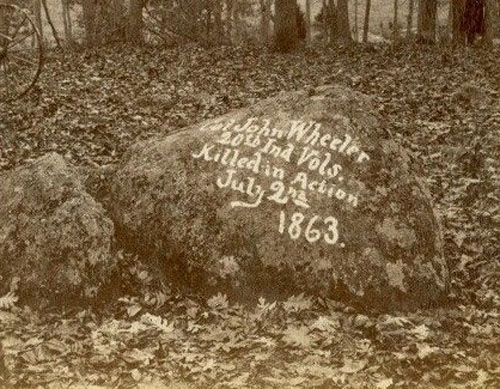

Located only a few yards from the monument to the 20th Indiana Infantry Regiment, which is located in the northwest corner of the intersection of Sickles Avenue and Cross Avenue, is a relatively small boulder which marks the place where Colonel John Wheeler, while commanding that regiment on horseback during the fierce fighting for the Wheatfield on July 2, was shot and killed. The boulder, which was originally painted instead of carved with the inscription “Col. John Wheeler 20th Ind Vols. Killed in Action July 2nd 1863.” is now often marked by a small U.S. flag:

(Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)A small stone marker nearby which was placed on top of a flat rock also had an inscription painted on it which marks the location where another Union colonel lost his life during that same fighting for control of the Wheatfield on July 2. Located just 10 yards directly behind the monument to the 5th New Hampshire Infantry Regiment, which is on the south side of Ayres Avenue just before reaching the intersection of Sickles Avenue and Cross Avenue, a simple looking “rock” still remains where Colonel Edward E. Cross, while commanding the First Brigade of the First Division of the Union II Corps, was mortally wounded. Although the painted inscription which once read “ON THIS SPOT FELL COL. CROSS 5 N.H.V. JULY 2, 1863” is no longer visible, you can still see several chisel marks on the back of the stone marker (see the bottom photo below):

(Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)Just a short distance away on the east side of Brooke Avenue is a rock associated with the brave action of Colonel John R. Brooke, commander of the Fourth Brigade of General John C. Caldwell’s First Division of General Winfield S. Hancock’s Union II Corps. Sent into the maelstrom at the Wheatfield on the afternoon of July 2 as just one of the many brigades sent in as reinforcements by General Hancock, Colonel Brooke launched one of the many counterattacks that day. Located roughly 45 yards behind the marker to his brigade down a footpath (visible in the top left photo below between the brigade marker and the monument to the 53rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment) is a small shoulder-high boulder which Colonel Brooke marked years later with an “X” (visible below the pen in the bottom left photo and in a closer view in the bottom right photo) upon which he claimed to have stood for a short time while directing the movements of his troops that day:

It is interesting to note that from what I have read, this boulder was discovered by Licensed Battlefield Guide Dave Richards in 1994 !!!

An even more recent discovery was made by Licensed Battlefield Guide Richard Rigney during the winter of 2012-2013. Located on a large boulder approximately 50 yards southeast of the George Weikert barn on Cemetery Ridge and about 15 yards south of a stone wall behind the house is a carving that marks the original burial sites of Captain Henry Fuller (see the "Lesser known and visited monuments and small markers" section on my “Off the Usual Path” page) and Lieutenant Willis Babcock, members of the 64th New York Infantry Regiment killed on July 2:

Located at “The Angle” on Cemetery Ridge are rocks that, although they were never marked in any way, is associated with Sergeant Major William S. Stockton, a member of the 71st Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel Richard P. Smith. During the hand-to-hand fighting on July 3 as General Lewis Armistead’s Confederate troops broke through the Union lines just north of the “copse of trees”, Sergeant Major Stockton and a few other comrades did not flee to the rear but remained at their posts and continued to fight until they were surrounded and then captured. Sergeant Major Stockton told his men to stay where they were and not head to the rear as prisoners, but to wait for his signal to escape. When an opportunity to do so soon arose, he gave the signal and led his men to safety back across the stone wall and to the ranks of the 72nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment just as they were about to charge. Turning around and without any weapons, Sergeant Major Stockton and his handful of comrades joined in the charge, and ultimately helped capture several Confederate prisoners. Oh, if rocks could talk ...

There is also a small and often overlooked rock carving further up on Cemetery Ridge near the Abraham Brian farm. Located roughly ten yards south of the monument to the 111th New York Infantry Regiment, there are three letters (perhaps CEH or CLH) on a flat rock:

A review of the regimental roster/muster roll of the 111th New York Infantry Regiment provides several possibilities, including Chauncy L. Hickok, who enlisted at age 18 as a corporal in Company H on August 4, 1862 to serve three years and was mustered out with the rank of sergeant on June 13, 1865 in Baltimore. It is entirely possible that he or another veteran who attended the dedication of their regimental monument in 1891 made the carving, but there is no documentation as to who actually did so.

There is also an interesting battle-related carving nearby on the southwest corner of the Jennie Wade House Museum located at 548 Baltimore Street, where Jennie Wade was killed by a Confederate sharpshooter’s bullet on the morning of July 3 --- the only Gettysburg civilian killed during the battle (for more information, go to https://www.gettysburgbattlefieldtours.com/jennie-wade-house/history). The carving was discovered by Licensed Battlefield Guide Tim Smith in the Summer of 2020 after finding a September 21, 1907 Adams County Independent newspaper article. The article stated that Private Adam F. Miller of Company I of the 75th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment passed by the house occupied by Mary Virginia “Jennie” Wade and her sister’s family during the fighting on July 1, and later used his bayonet to carve his initials “A F M” in a brick on the southwest corner of the building on the morning of July 2. In 1907, he returned to Gettysburg 44 years after the battle and carved his company and regiment under his name. Both are still located and visible on the house today, although the “M” is obscured by the downspout:

Before going over to a National Park Service lecture one Saturday in February of 2009, I stopped at Stevens’ Knoll and noticed a small U.S. flag placed at a small boulder roughly 10 yards behind the monument to Captain Greenleaf T. Stevens’ Battery E, 5th Maine Light Artillery. I had never heard of this being done at this spot, so I did some research via “Googling” and emails. What I found out was that Private John F. Chase, a cannoneer in that battery who would be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his gallantry at the Battle of Chancellorsville, was probably the soldier who suffered the most wounds (48) during not only the Battle of Gettysburg but also the entire Civil War. Private Chase also lost his left eye and right arm, and lay on the battlefield for two days. Not only that, but he was later placed on a burial cart when it was discovered that he was still alive. So, if this spot is not known as “Chase’s rock”, perhaps it should be !!!

(Photo courtesy of the Maine State Archives --- John Chase is on the far left)Another interesting rock like the one above is a much larger boulder located roughly 100 yards east of the Pennsylvania Monument on Cemetery Ridge. This boulder is also associated with a Union battery, Captain Robert B. Hampton’s Battery F of the Pennsylvania Independent Light Artillery (It should be noted that Captain Hampton was killed two months earlier at the Battle of Chancellorsville). Dead and wounded cannoneers from that battery were reportedly taken behind the boulder for refuge during the cannonade preceding Pickett’s Charge on the afternoon of July 3. The boulder has since been referred to as “Hampton’s Battery Rock” and although there is no marker, U.S. flags and wreaths can occasionally be found behind the east side of the boulder:

(Photo courtesy of Robert Brown)For more information on Hampton’s Battery and Hampton’s Battery Rock, go to the website at http://hamptonsbatteryf.com.

During the Fall of 2020, I learned about Private Samuel Shilling of Company E of the 148th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment and the interesting story about his wounding at the Battle of Gettysburg. Samuel Shilling returned to Gettysburg for the 1913 50th Anniversary Reunion and was photographed at the rock where he was taken after being wounded in the right hip by an artillery shell on the afternoon of July 3:

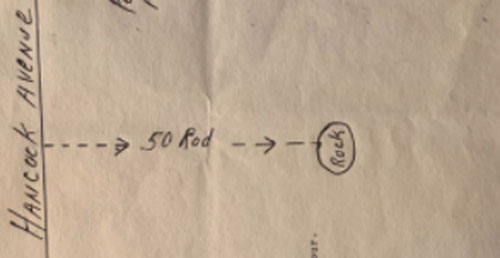

(Photo courtesy of Linda Lavelle Kerner)As I began working on the next update to my website in the Winter of 2020, I was able to contact two direct descendants of Private Samuel Shilling: Linda Lavelle Kerner and Doug White. Doug was gracious enough to share his family’s map on the back of their copy of the 1913 photograph of the location of the rock with me and about his visit to the site in 2001.

(Section of the map courtesy of Doug White)Using the map and the 1913 photo and keeping in mind that the area has changed since 1913 and 2001 with tree-cutting done in the area by the GNMP, several of my Civil War buffs (Linda Bean, Suzie Cheeks, Bob and Kim Fissel, Tammy Harkleroad, Barry Larkin, Alan Leeti, Keith McGill, and Dale Miller) and I were able in early January of 2021 to find what is generally agreed upon as the rock and is located about 40 yards east of Hampton’s Battery Rock:

Private Samuel Shilling enlisted on August 7, 1862 at the age of 16. He was captured at the Battle of Ream’s Station in Virginia on August 25, 1864 and was eventually taken to the Confederate POW camp in Salisbury, North Carolina after spending some time at Libby Prison and Belle Isle Prison in Virginia. Shilling escaped from Salisbury, however, on February 10, 1865 and eventually made it to Union lines in April. Here is one more 1913 Gettysburg photo courtesy of Shilling descendant Linda Lavelle Kerner from Pennsylvania:

(Photo courtesy of Linda Lavelle Kerner)It should be noted that there is a small boulder behind the barn on the Abraham Trostle farm where General Daniel Sickles, commanding the Union III Corps, was briefly taken behind in order to safely ascertain the extent of his wounds after he was hit by cannon fire and lost part of his right leg (see the “Witness trees” section on my “Odds and Ends” page). The boulder is roughly 40 yards east of the small “Sickles Wounding Monument” as shown in the photo below on the left:

On the other side of Wheatfield Road is a lesser known rock associated with a wounded Union artilleryman, Private John Norwood of Captain John Bigelow's 9th Massachusetts Light Artillery Battery of the Artillery Reserve. After retiring eastward by prolong from its initial position near the Peach Orchard, the battery halted to limber their guns in the small orchard south of the Abraham Trostle farm buildings. As Norwood and a driver were desperately trying to limber the number five gun, Norwood was shot through the lungs with the bullet lodging near his spine. Norwood collapsed near the trail of the gun as the battery was overrun by Confederate infantry, some of whom later assisted in moving Norwood about fifty yards to the shelter of a large tree and boulder. In the final minutes of the fighting at dusk that day, some of the retreating Confederates took shelter on the other side of the boulder and fired over it at Union troops who eventually recaptured the battery’s abandoned guns.

Norwood survived the battle and the war (he was discharged in February of 1864 because of his wound --- the bullet was still lodged near his spine), and returned to Gettysburg in the Spring of 1883 to help determine where the monument to Bigelow’s Battery should be placed. The boulder can still be found about 50 yards southwest of the Abraham Trostle house on Wheatfield Road:

(view facing southwest toward the Peach Orchard on the other side of the ridgeline)

(view facing northeast toward the Abraham Trostle House)Another rock associated with wounded soldiers on July 2, 1863 can be found on Houck’s Ridge on the west side of Crawford Avenue approximately 60 yards west of the tablet and two cannons of Captain James E. Smith’s 4th New York Battery. The rock involves the story of Sergeant Major George Wesley Hancock Stouch of Company B of the 11th U.S. Infantry Regiment. During the retreat of the Union troops on Houck’s Ridge and in the Wheatfield, Stouch (who was actually born in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in 1842 but moved with family members to Kentucky in the mid 1850’s) was wounded and captured along with several wounded soldiers of his regiment at the rock shown in the photos below while helping to carry them to the rear. Stouch and his fellow soldiers were later freed by Union troops of General Samuel Crawford’s Division of Pennsylvania Reserves. Stouch survived the war and later returned with his family to the Gettysburg battlefield on July 2, 1886:

(Photos courtesy of the GNMP)

There is one rock carving on the southern crest of Devil’s Den which is located hear the left flank marker of Captain James E. Smith’s 4th New York Battery. The finely chiseled rock inscription, “P. Noel,” is apparently not one that was done by a soldier but by a local stone-cutter by the name of Park Noel, who had worked on several of the battlefield monuments:

Located nearby is a very small and lesser known rock carving on the summit of Devil’s Den near the monument to the 99th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment that he had seen in late May of 2021. The lettering is only about 1 inch tall and appears to say “C A S E Y” and is located near the top of the far left portion of the boulder shown in the photos below (photos courtesy of Dale Miller and Bob Fissel):

In a speech given by Albert Magnin during the dedication of the monument on September 11, 1889:

“And among that number, my comrades, are those of the Ninety-ninth, who on that fateful day, did and dared and died that we might enjoy the priceless heritage of liberty. And of those I call to mind was Corporal James Casey of Company K, whose twin brother, Sergeant Amos Casey, now stands before me holding the dear old flag for which his brother died. On that eventful day, as our lines fell back, Corporal Casey, industriously applied himself to breaking the guns that strewed the ground to prevent them falling into the hands of the rebels. He found one that was loaded, and remarking to Major Moore that he was going to have another shot, he fired, and at the same moment was himself struck. Major Moore and Sergeant Graham attempted to bring him from the field, but he bravely told them to lay him down and save themselves, and nevermore was Corporal Casey heard of. It was a death wound. He was a brave lad, and the ghouls who robbed his body and thus prevented his identification knew it, for upon his breast he wore the Kearny Badge, and you, men of the Ninety-ninth, know none but brave men wore that. brave men wore that.”

It is possible that Amos Casey carved his (and his brother's) last name when he was present for the dedication of the monument to honor his brother James. Thus far, I have been unable to document this theory as to who made this carving, but it would seem to make sense.

Similar well-chiseled carvings can be found on the summit of Big Round Top. If you stand halfway between the monuments to the 5th Pennsylvania Reserves and to the 12th Pennsylvania Reserves and walk east roughly 10 yards behind the rocks (see the top left photo below), you will come upon a larger rock (see the top right photo below) containing the initials “WHG” and WHH” as well as “J. Noble,” “J. Hinchliff,” and “J. Crumlish”:

Are they the names of solders (there was a soldier by the name of James B. Noble who had served in the 118th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment whose monument is farther down the northern slope of Big Round Top), or are they the names of other stone-cutters like Park Noel ???

On November 19, 2021, I had the privilege of meeting amateur historian and fellow Battle of Gettysburg buff Peter Guglieri from New York. Peter had told me a few months ago about two obscure rock carvings that I had never heard about --- two rock carvings in the Devil’s Kitchen on Big Round Top.

The carvings are located about five feet inside on the right side of the narrow crevice shown below and on the other side of the Devil’s Kitchen opposite of the photos above:

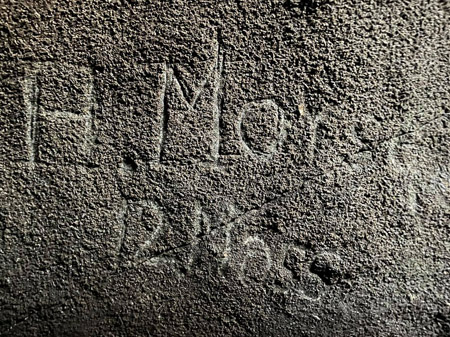

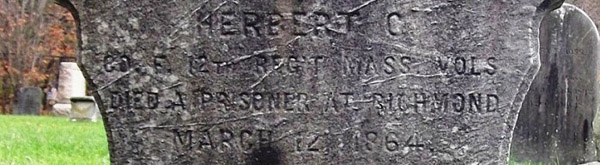

Peter explained to us that he found the carving below on March 27, 2021 and through his research determined that it was related to Private Herbert C. Morse of Company F of the 12th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, who had been captured during the fighting on July 1, 1863.

Private Morse died in a Confederate prisoner of war camp in Richmond, Virginia in March of 1864, and that information is on his gravestone in West Boxford, Massachusetts:

(Photos courtesy of John Glassford and FindaGrave.com)

Official records do list another soldier named Morse in that regiment also with a first name starting with “H” (Henry P.), but although he survived the war that soldier did not enlist in that regiment until December of 1863 and would not have been at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Peter then explained that he found the carving below on June 13, 2021 in the same crevice:

Based on his research regarding Private Herbert C. Morse and him being captured, Peter went through the lists of Union soldiers who were captured on the first day of the battle. Only one was the 19th. Then he went through their list until he found those initials and discovered that Private James H. Edwards of Company I of the 19th Indiana Infantry Regiment was also captured during the fighting on July 1, 1863. Sadly, Private Edwards also died in a Confederate prisoner of war camp in May of 1864 (in this case, in Andersonville, Georgia).

(Photos courtesy of Andrew Frye and FindaGrave.com)Since both soldiers died, they obviously didn’t make the carvings after the war during a reunion visit or regimental monument dedication. Therefore, it would seem feasible that the Confederate Army used the Devil’s Kitchen as a temporary holding area for at least some Union prisoners as the Union prisoners were rounded up and sent South, and that both of these soldiers were held in that particular crevice at one point during the Battle of Gettysburg. For the sake of argument, if former comrades or family members did visit Gettysburg after the war and made the carvings, then why did they make the carvings where they are not easily seen? If anyone has has a better theory about these carvings, please let me know by sending me an email at randydrais@gmail.com.

PLEASE NOTE THAT THE CREVICE IS EXTREMELY NARROW AND MORE IMPORTANTLY,

AS IN THE CASE OF MOST LOCATIONS ON THE BATTLEFIELD, SNAKES MAY BE

PRESENT (INCLUDING COPPERHEADS AND RATTLESNAKES), ESPECIALLY IN

ROCKY AREAS LIKE THE DEVIL’S KITCHEN).As of December of 2015, the most recent discovery of a rock carving was found in April of 2014 by author Tom Elmore and I. We were able to locate a rock where two Confederate artillerymen were killed on Seminary Ridge north of McMillan’s Woods by the same Union shell during the cannonade on July 3. It marked the temporary graves of Hugh Thomas "Tom" Pendleton and James R. Maupin, and one of the accounts stated that “….I tried to chisel his name on the rock but it was so hard that I was enabled only to make a cross mark." Tom Elmore (shown below) and I shared our findings and information with the Gettysburg National Military Park, which later documented the GPS location for their records. A more detailed account can be found in the January 2015 issue of Gettysburg Magazine:

A rock carving that I had heard about in 2018 which was reportedly on private property actually turned out to be on GNMP land and roughly only 40 yards east of the auxiliary parking lot of the main Visitor Center. After a year of research, two on-site attempts, and a tip as to its location, I was able to find the boulder and the carving involving Lieutenant Joshua Simster Garsed of Company B of the 23rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment. After spending most of their time defending Culp’s Hill on July 2, on the afternoon of July 3, the 23rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment was pulled off of Culp’s Hill and sent westward to the right and rear of General Meade’s headquarters near the Taneytown Road as part of the attempt to reinforce the Union center. Around 5:30 P.M. that day, Lieutenant Garsed was struck by a Confederate Whitworth artillery shell between the right shoulder and neck area and was instantly killed.

It is said that Frank Garsed, Joshua’s brother, took one final trip to Gettysburg in 1914 with William J. Wray, the regimental historian of the 23rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment. During this visit, they carved “JSG” on the boulder located at the approximate location where Lieutenant Joshua Simster Garsed was killed:

(Photo courtesy of Tom Miller)

(Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Other carvingsOne of the battlefield structures which has carvings made by soldiers is the famous Edward McPherson barn just south of the Chambersburg Pike on the east side of Stone Avenue. I had heard of these carvings, and learned more about them when I read the January 25, 2010 edition of http://www.gettysburgdaily.com. Located roughly 9 inches above the east (right) louvered window on the south side of the barn, “JCT 143rd P.V.” and “SMG Sept 12 1889” can be seen:

It is reported that “JCT …” was made by Jonas C. Tubbs and “SMG …” was made by Singleton M. Goss; both were members of Company F of the 143rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment and were present at the dedication of their regiment’s monument nearby on September 11, 1889. For more information and videos, see the January 25, 2010 story by Licensed Battlefield Guide Rich Kohr at http://www.gettysburgdaily.com/?p=6627.

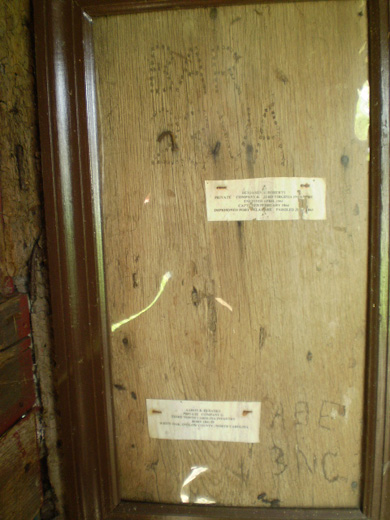

Another structure is the Daniel Lady barn, located on the Daniel Lady farm approximately .2 of a mile east of Benner's Hill on the north side of the Hanover Road (Route 116), which served as the division headquarters and a field hospital of Confederate General Edward Johnson's Division (see the “Daniel Lady farm” section on my “Off the Usual Path” page). Located inside the barn on a door jamb are two large carvings, “BAR 23 VA” and “ABE 3 NC”:

There was a member of the 23rd Virginia Infantry Regiment by the name of Benjamin A. Roberts, who may have made the one carving. The other carving could have been made by Aaron B. Eubanks, a member of the 3rd North Carolina Infantry Regiment.

There is another carving in the back of the barn on a window sill that reads "44 VA JB". There are at least six members with those initials in the 44th Virginia Infantry Regiment, but there is also the possibility that “JB” could be an abbreviation for “Jones’ Brigade” of which the 44th Virginia Infantry Regiment belonged:

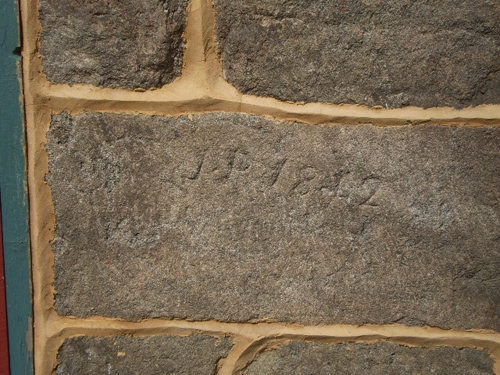

Located on the outside of the barn on the south wall roughly 24 inches above the ground is the carving “JP 1842” – the carving is by Jacob Powers (of Powers’ Hill), who built the foundation for this barn and several others in the Gettysburg area:

There are also several carvings on the east end of the south wall of the remnants of the barn on the George Rose farm located south of the Peach Orchard off to the east side of the Emmitsburg Road. At least one of the most prominent carvings may have been made by a soldier who later came back to Gettysburg in July of 1888 for the 25th anniversary of the battle:

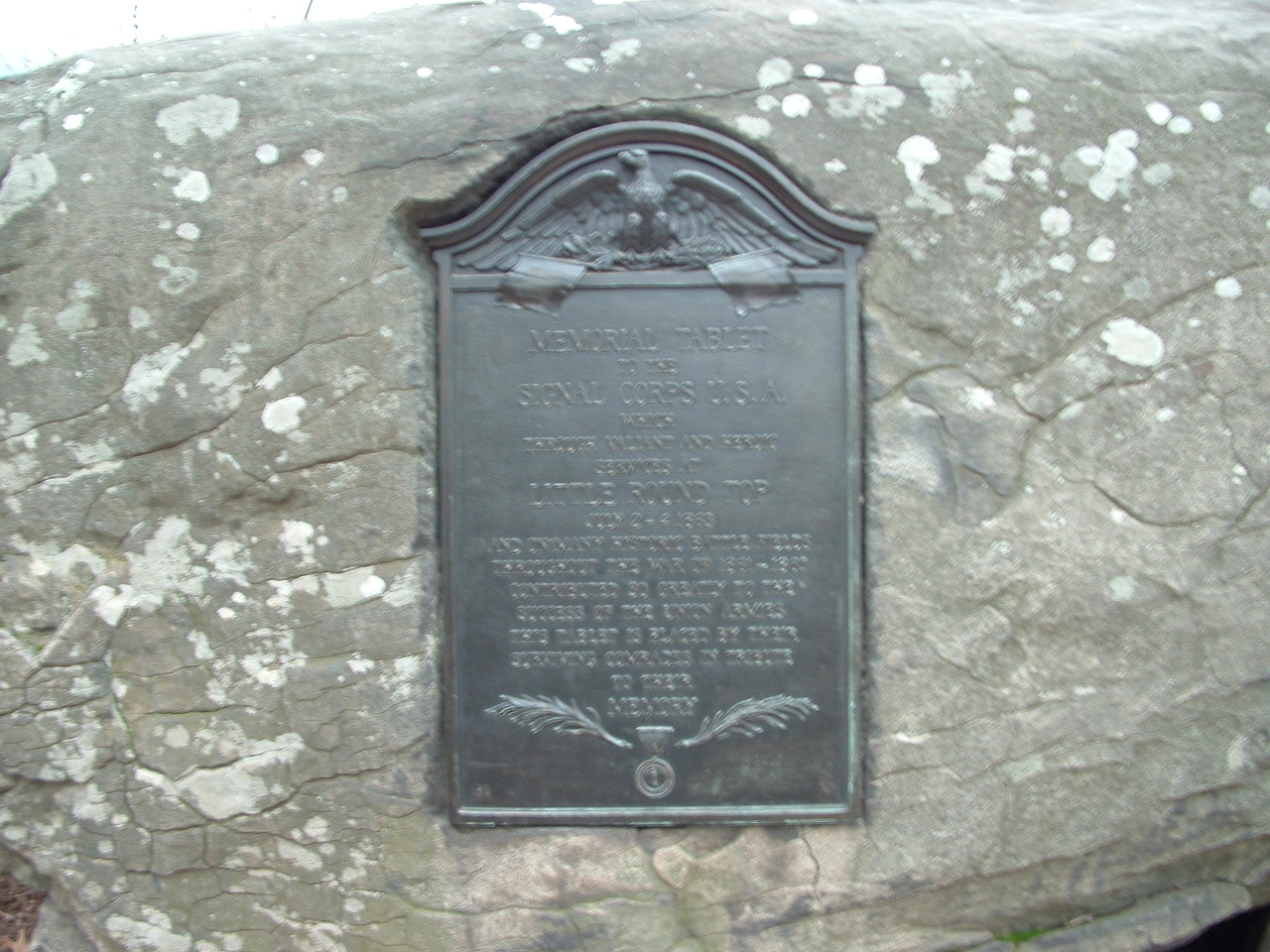

The Union Army Signal Corps "Tour"

While everyone knows that Little Round Top was the location of a Union Signal Station, there is a plaque on the rock where it was primarily operating from (see the photos below):

I have found a website dedicated to the Union Army Signal Corps, which has a 13-stop self-guided "tour" of the Signal Stations used during the Gettysburg Campaign. For those of you interested in this aspect of the battle, I recommend http://www.civilwarsignals.org/gburgsignals/gburgtour.html --- it includes a few rare photos as well as the actual text of many dispatches and reports by those soldiers manning the stations, and they are indeed interesting reading.

The Lutheran Theological Seminary Cupola "Tour"Gettysburg’s Seminary Ridge Museum in Schmucker Hall of the Lutheran Theological Seminary opened on July 1, 2013. The museum exhibits address the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg and the role the building played, including its use as an observation point and its role as a field hospital for more than 600 wounded soldiers, both Union and Confederate. In addition to audio and video programs, murals, and artifacts, tours of the cupola will also be available. In previous years, public access to the cupola was limited to two Saturdays a year (one in April and one in November) when the Adams County Historical Society allowed people (for a donation) to go up in the well-known cupola and get a view of the battlefield and a feel for what it must have been like for Union General John Buford as he watched the opening action on July 1 and anxiously waited for the arrival of General John Reynolds' I Corps. For more information, go to http://www.seminaryridgemuseum.org.

(looking west toward Reynolds Avenue)

(looking northwest toward McPherson's Barn)

(looking north toward the bridge over the railroad cut)

(looking northeast toward Gettysburg College)

(looking east toward the town)

(looking south toward the Round Tops)

Views from the Pennsylvania MonumentOne great year-round observation point on the battlefield is the upper level of the Pennsylvania Monument. Dedicated in 1910, this well-known monument/memorial underwent an extensive two-year renovation in 2002 - 2003 which cost approximately $1.4 million. One of the great benefits of the renovation was that the upper level, which had been closed for many years due to structural and safety concerns, was finally reopened to the public and once again offers an excellent and unique vantage point on Cemetery Ridge to view much of the battlefield. Here are some of my photos (looking from the south to the northeast):

(south toward the G. Weikert farm and Round Tops)

(south southwest toward the A. Trostle farm)

(southwest toward the observation tower)

(west southwest toward the J. Sherfy farm)

(west toward the Virginia Monument and N. Codori farm)

(northwest toward the major area of Pickett's Charge)

(north along Cemetery Ridge toward Ziegler's Grove)

(northeast toward the Taneytown Road and Culp's Hill)

Evergreen CemeteryVisitors often take time to explore the Soldiers' National Cemetery, the "official" site of President Lincoln's "Gettysburg Address", but many of them tend to overlook visiting the adjacent cemetery on the other side of the fence, Evergreen Cemetery. It is not only the final resting place of Virginia "Jennie" Wade, the only civilian known to be killed during the battle, and John Burns, the famous "citizen soldier" of the battle, but also of many other notable and world-famous people (see the webpage at http://www.evergreencemetery.org).

In addition, in one area of the cemetery I counted 69 Union soldiers (2 unknown) and 2 Confederate soldiers who are still buried there as well:

Both Private Hooper P. Caffey, a member of the 3rd Alabama Infantry Regiment, and Sergeant Matthew Goodson, a member of the 52nd North Carolina Infantry Regiment, were wounded in battle and later died at a Union II Corps hospital, where their remains were not found until a few years later in 1866 and then moved to Evergreen Cemetery. However, a public outcry in 1867 about Confederates being buried in the cemetery resulted in their remains once again being moved --- this time to a more secluded location. The truly sad part is that the exact spot is no longer known, and the markers seen in the photograph above do not really indicate their final resting place.

Of the many tombstones damaged during the battle, there are at least three still in existence on the cemetery grounds:

What is also interesting is that two obelisk tombstones were reportedly dismantled by Union troops to prevent Confederate artillery on Benner’s Hill from using them as a sighting device for targeting purposes. One of the tombstones reportedly dismantled during the battle belonged to George and Catharine Smyser (shown below on the left). The other one (shown below on the right) belonged to J. B. and Catharine McPherson, the parents of Edward McPherson, a U.S. Congressman from the area from 1859-1863 and the owner of the McPherson Farm on the west side of town.

Just inside the gatehouse entrance, the Gettysburg Civil War Women's Memorial, a bronze statue of Elizabeth Thorn, was dedicated in November of 2002 to honor the many unsung women civilians of the battle. The wife of the cemetery caretaker, Peter Thorn (who enlisted in the 138th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment in 1862), Elizabeth was left in charge of the cemetery. Despite being six months pregnant and also having to care for three sons, Elizabeth Thorn dug graves for and buried approximately 100 soldiers during and after the battle. To read more about her and all the notable people buried in Evergreen Cemetery (including a member of baseball's "Hall of "Fame" and a famous singer/actor), I recommend reading "Beyond the Gatehouse" by Brian A. Kennell, the caretaker of Evergreen Cemetery since 1991.

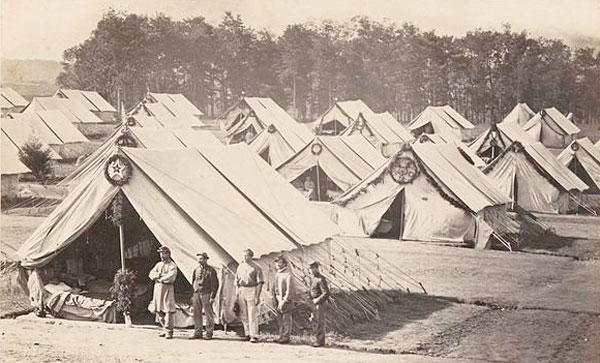

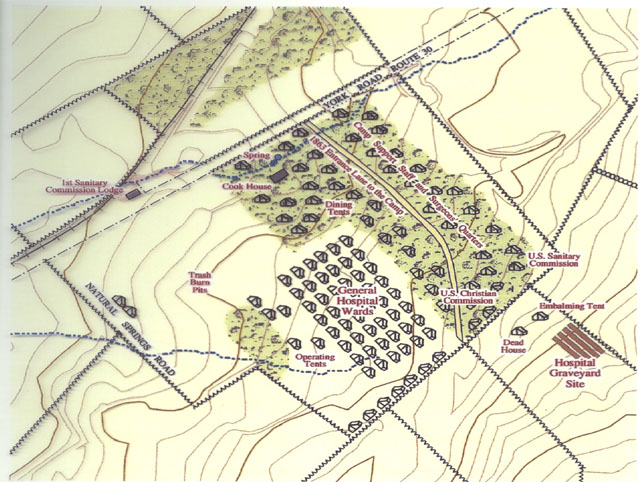

Field Hospitals and Camp Letterman

Located on the south side of Route 30 (the York Road) approximately 1.5 miles east of Gettysburg is the easily overlooked Army of the Potomac Medical Department monument to all the field hospitals of each Union Army Corps as well as honoring and marking the location of Camp Letterman, a general hospital on the George Wolf farm of more than 500 tents where approximately 3,500 sick and wounded soldiers, both Union and Confederate, received medical treatment and convalesced from July 22 until November 20 of 1863, when the camp closed.

(Photo courtesy of the National Archives)

(Map courtesy of Licensed Battlefield Guide Phil Lechak and the GNMP)The photograph below is of the Jacob Weikert home on Taneytown Road, which later became much better known as a result of a book written after the Civil War by Tillie Pierce Alleman, a 15-year-old girl at the time, of her recollections and experiences of the battle, including helping to take care of wounded Union soldiers at this farmstead. Tillie's home in Gettysburg (which housed several wounded Union soldiers after the battle) still stands on Baltimore Street. Tillie's book is still in print and readily available, and is well worth reading in order to get a young civilian's perspective of the battle (see my "Books Worth Reading" page).

To read more about the field hospitals, I recommend reading "A Vast Sea of Misery - A History and Guide to the Union and Confederate Hospitals at Gettysburg" by Gregory A. Coco.

Horseback riding on the battlefieldFor those of you who enjoy horseback riding or are a novice at it, and would like to view the battlefield from a cavalryman's or mounted officer's perspective, I heartily recommend taking an escorted horseback tour of as much of the battlefield as you can. You will have a unique opportunity to see many areas of the battlefield that would normally require walking some distance from your car, and the different perspective will be an educational one for any buff.

I know of three places/groups that currently do this: they are the Artillery Ridge Campground, the Hickory Hollow Farm, and Confederate Trails of Gettysburg. Artillery Ridge Campground (http://www.artilleryridge.com) is located on Taneytown Road on the east side behind Little Round Top, while Hickory Hollow Farm (http://www.hickoryhollowfarm.com) is located about 5 miles west of Gettysburg and has riders meet at their battlefield trail ride starting point at the McMillan Woods Campground on West Confederate Avenue/Seminary Ridge. Confederate Trails of Gettysburg (http://www.confederatetrails.com) also has riders meet at their battlefield trail ride starting point at the McMillan Woods Campground on West Confederate Avenue/Seminary Ridge.

I have ridden many times in the past several years at Artillery Ridge Campground, and it has always been a fun and worthwhile experience, especially as the National Park Service continues its long-term efforts to restore the battlefield as much as possible to how it appeared in 1863. In June of 2011, I took a one-hour trail ride by Hickory Hollow Farm. It was a very nice experience and covered the western side of Seminary Ridge down to and over to the Henry Spangler farm. Confederate Trails of Gettysburg covers essentially the same route(s), so if you are interested in viewing a portion of the battlefield from the Confederate perspective, either of these two facilities will provide you with a great opportunity to do so. To view a portion of the battlefield from the Union perspective, I recommend using Artillery Ridge Campground.Just one reminder --- reservations over the summer fill up rapidly, so try to make them as early as possible.

Side-trip to Emmitsburg, MarylandI had always planned on taking a side-trip to Emmitsburg, Maryland, the home of Mount St. Mary's University and Indian Lookout, a location where many students and residents of the town actually observed much of the Battle of Gettysburg using telescopes, opera glasses, and the like. While I had read about this in many books, and knowing that there was a Union Signal Corps station during the battle in the mountains above Emmitsburg, I still found it a little hard to believe that at a distance of 10-15 miles, an individual could see that much even with a telescope. I was still skeptical even after reading a detailed account of this which I found at http://www.emmitsburg.net/history/article_index/war.htm.

I brought up this issue with Michael Strong, a very knowledgeable Licensed Battlefield Guide, during a 2-hour tour I took with him. As it happened, we were on Oak Ridge at the time, and he was easily able to point out the mountains outside of Emmitsburg. Even without having binoculars with me that day, I became less skeptical. Nevertheless, as they say, "seeing is believing", and I am anxious to take a side-trip to see exactly how much of the battlefield you can see from there.

I took the Second Annual Historic Emmitsburg Civil War Walking Tour on early Friday evening, June 27, 2008. Led by Emmitsburg area historian (and Civil War reenactor) John Miller, the 90-minute walking tour was enjoyable as well as educational --- I learned more about and saw for the first time the charming little town of Emmitsburg, which is worth visiting even if you are not interested in its role in the Gettysburg Campaign.

For more information and photographs I took from Indian Lookout, go to my “Side-Trips” page.

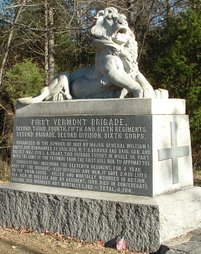

Unusual monumentsThere are approximately 1,320 monuments, markers, and tablets of various sizes and shapes on the battlefield. That being said, there are many unusual looking ones, four of which are shown in the photographs below (from left to right):

The First Vermont Brigade (located on Wright Avenue near Big Round Top)

The Tammany Regiment (located on Cemetery Ridge near the High Water Mark)

The 90th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment (located on Oak Ridge near the observation tower)

The 73rd New York Infantry Regiment (located in Excelsior Field off the Emmitsburg Road)

While all of the monuments have their very own unique and interesting history, the monument to the 90th Pennsylvania Infantry, shaped in the shape of a tree shattered by artillery fire but still holding a bird nest, is even more so. Legend has it that during the battle on July 1, a tree near that regiment's position was struck by cannon fire, knocking a robin's nest filled with baby birds to the ground. One soldier picked up the nest and climbed the tree, placing the nest and baby birds back where they belonged. One version of the legend has it that the soldier did this while still under heavy fire, and another one has it that Confederate soldiers, once they observed what he was doing, ceased their fire until he completed his "rescue mission." True or not, it still makes for an interesting story to tell.

Another interesting feature about this monument is that while most regimental flank markers are typically small plain square or rectangular markers, the flank markers for this regiment is in the shape of tree stumps:

Here are three more unusual monuments that are among my favorites (from left to right):The 123rd New York Infantry Regiment (located along Slocum Avenue on Culp's Hill)

The 88th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment (located on Oak Ridge near the observation tower)

The 53rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment (located on Brooke Avenue south of the Wheatfield)

The monument to the 123rd New York Infantry Regiment has Clio, the Greek muse of history, atop it:

The monument to the 88th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment has everything from two cannon tubes, a cap, canteen, cannon balls, a rifle, cartridge belt, haversack, flag, drum, and even an eagle:

The monument to the 53rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment has a soldier overdressed for fighting in July:

There are two other monuments with soldiers who are overdressed, and they are both located on East Cemetery Hill. The monument to the 7th West Virginia Infantry Regiment can be found about 15 yards southwest of the equestrian monument to General Oliver O. Howard:

The monument to the 4th Ohio Infantry Regiment can be found approximately 45 yards south of the equestrian monument to General Winfield S. Hancock:

There is unique monument or marker on East Cemetery Hill that is in the vicinity of the two monuments above but is often ignored because of its small size and the fact that the inscription is no longer legible. The small pedestal with a white "cap" which contains two crossed cannon tubes was erected around 1879 as a simple monument/marker to Battery B, 1st Pennsylvania Light Artillery, commanded by Captain James H. Cooper of the Union I Corps Artillery Brigade:

To read more about this monument/marker and what was inscribed on it, read pages 108-109 of the book, "Silent Sentinels: A Reference Guide to the Artillery at Gettysburg" (see my "Books Worth Reading" page).

There is another unusual monument, honoring the 29th Ohio Infantry, located on Culp's Hill, but it is unusual in quite a different way. While I was walking there two years ago during a National Park Service one-hour "Ranger Walk", I noticed something odd about the monument --- the "S" in "US" is backward. To my knowledge, no one knows when the error was first detected, and why it was not (if it was even possible) corrected:

In addition, there are three “typos” on the back of this monument --- can you spot them ???

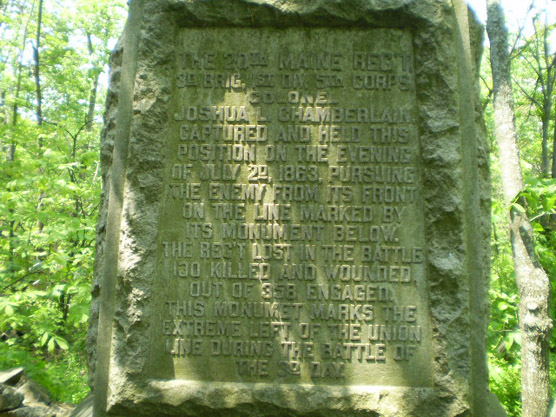

Another monument with a "typo" is the monument to the 20th Maine Infantry Regiment which is located approximately 75 yards below the summit of Big Round Top (see my "Off the Usual Path" page). If you look closely, the second time the word "MONUMENT" appears, it is incorrectly spelled "MONUMET" only a few lines later:

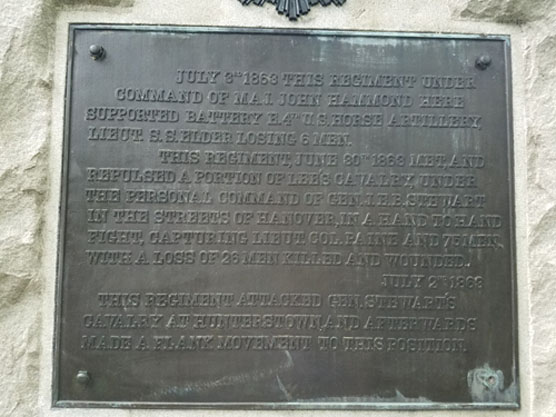

Located nearby on Bushman Hill are two seldom visited monuments (see the “The South Cavalry Battlefield --- the other cavalry action on July 3” section of my “Off the Usual Path” page), and one of them has a “typo” on the back of it --- the monument to the 5th New York Cavalry Regiment commanded by Major John Hammond:

Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart’s name is spelled “Stewart”:

(Photo courtesy of Barry Larkin)Yet another monument with a “typo” is the monument to the 155th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, which can be found on the northern half of the summit of Little Round Top (see my “Faces of the battle” section at the top of this page):

At first glance, the spelling of Pittsburgh without the “h” may not raise an eyebrow, especially since the spelling of many other cities has changed over time. However, while it is true that from 1890 through 1911 Pittsburgh was actually spelled “Pittsburg”, the monument was dedicated in 1886 !!!

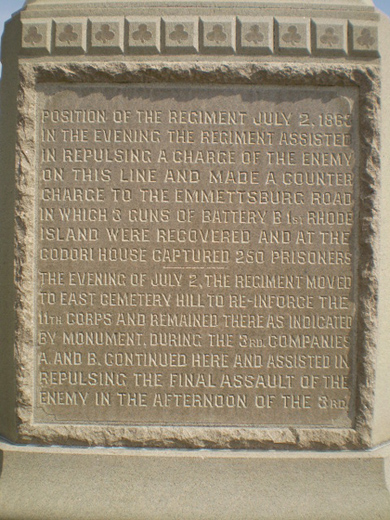

Another “typo” can easily be found on the south face of the monument to the 106th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel William L. Curry. Located in front of the famous “copse of trees” on the west side of Hancock Avenue along Cemetery Ridge, the monument has “Emmitsburg” spelled “Emmettsburg”:

I checked with Emmitsburg area historian and Civil War reenactor John Miller, who informed me that the most common spelling during the Civil War was “Emmetsburg” and that he has also seen it spelled as “Emittsburg” and “Emmittsburg” although the land map in 1858 that laid out the town has “Emmitsburg”. John added that it was spelled “Emmittsburg” because of the fact the town founders had spelled their name as Emmitt. The extra "t" was dropped sometime after the Civil War. So the monuments should have technically spelled it as “Emmittsburg” instead of “Emmettsburg”. So there you go (and many thanks, John !!!).

Another monument with what could be considered a “typo” is on the smaller of the two monuments to the 27th Connecticut Infantry Regiment (the larger monument is in the Wheatfield), which is located southwest of the Wheatfield along the east side of Brooke Avenue:

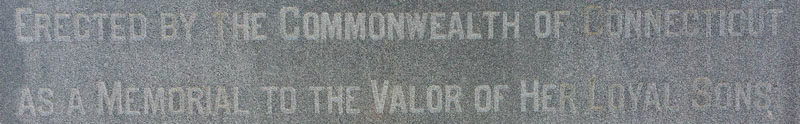

On the rear of the monument is inscribed:

However, only Kentucky, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Virginia are technically considered a Commonwealth. Interesting, wouldn’t you say?

The monument to the 5th New Hampshire Regiment, located on the south side of Ayres Avenue just before reaching the intersection of Sickles Avenue and Cross Avenue (see the “Rock carvings and inscriptions” section above on this page), has bronze plaques on each of its eight sides that contain the names of soldiers who were killed or mortally wounded during the battle, but early photos of the monument do not show the plaques. If you look closely above the top edge of two of the plaques, you can still see some of the lettering of those soldiers’ names. Were the plaques added later because of “typos” or that other names had to be added or removed ???

Located on the east side of East Cavalry Avenue approximately .4 of a mile north of the Hanover Road (Route 116) on the East Cavalry Battlefield, the large stone marker for Batteries E and G of the 1st U.S. Artillery, commanded by Captain Alanson M. Randol, has a “typo” of a different sort: it states that the Batteries had 4 12-pounder Napoleon cannons when they were actually equipped with 3-inch Ordnance rifles:

While it is not an actual “typo”, the monument to General James S. Wadsworth, the commander of the First Division of the Union I Corps, which is located just north of the famous “railroad cut” on the east side of Reynolds Avenue, is unusual in that one of the two decorative “medallions” of the State Seal of New York appears to be unfinished. In fact, the “unfinished” medallion represents a circle, the badge symbol of the Union I Corps:

What is also interesting to me is that not all the monuments to New York infantry regiments in the Union I Corps have a circle (or circles), but circles can be found on the monuments to other regiments such as the 6th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment and the 88th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment as well as the monument/statue on Oak Ridge to General John C. Robinson, who commanded the Second Division of that Corps, and the monument/statue of General Abner Doubleday on McPherson’s Ridge:

So when you see a monument with a blank circle(s) on it, look to see if the regiment belonged to the Union I Corps.

Located on McPherson’s Ridge along the east side of Reynolds Avenue roughly 150 yards south of the intersection of Meredith Avenue is the monument to the 80th New York Infantry Regiment, also known as the Ulster Guard. The monument has the “Red Hand of Ulster” (a symbol of Irish politics and identity) depicted at the top, but if you look closely, the thumb appears to be from the wrong hand (turn your right hand so that you are looking at you palm and you will see what I mean). Did the sculptor make a mistake or did he simply use “artistic license” in order to give the hand more detail?

There is also a small marker to the 80th New York Infantry Regiment that is located on Cemetery Ridge along the west side of Hancock Avenue roughly 80 yards south of the large obelisk monument to the U.S. Regulars (see my “More Odds and Ends” page), and this small marker commemorating the regiment’s participation in the repulse of Pickett’s Charge on July 3 also has the same odd-looking hand on it:

In any event, if you would like to learn more about the legend behind the Red Hand of Ulster, go to http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Hand_of_Ulster.